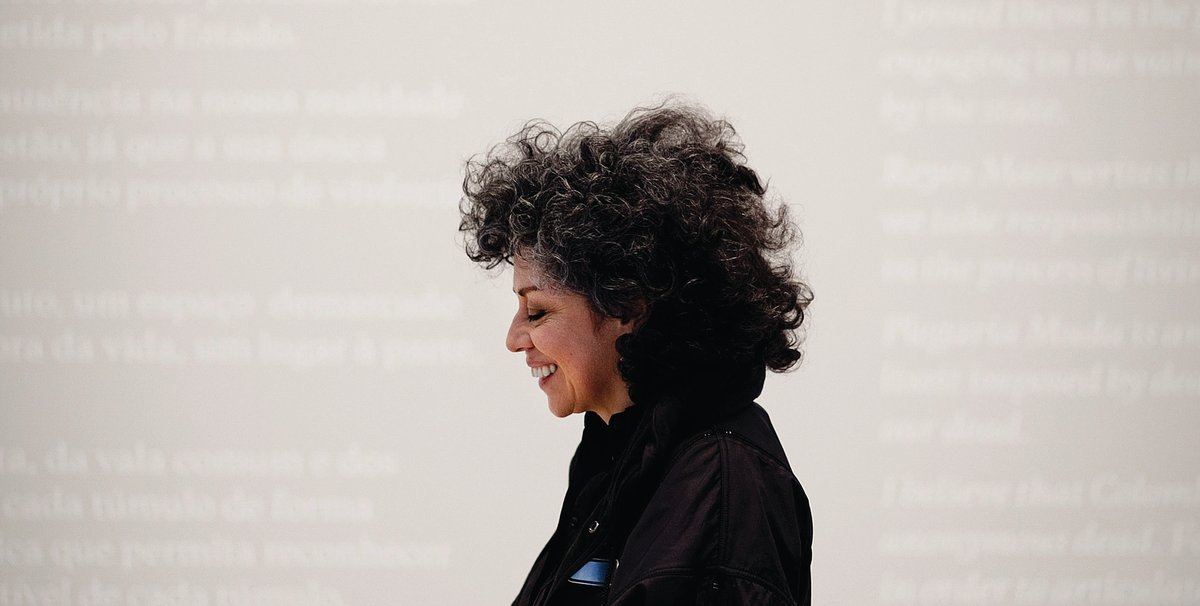

Thirty years is a long time to mourn. But that is what the Colombian sculptor Doris Salcedo has done through her work, which since the late 1980s has taken the victims of political violence and social marginalisation as its subjects. “During this time I have remained immersed in mourning; my work has been the work of mourning, and a topology of mourning,” the artist said in 2014, when accepting the Hiroshima Art Prize, which recognises artists whose work furthers the aim of international peace.

Rather than stand as implacable memorials, however, her sculptures and public installations appear as somewhat incredible objects that are also elegies to the people who have been lost through never-ending cycles of violence. Each work starts with serious research into a specific incident or series of events, and Salcedo often interviews the families of victims first-hand to gather testimonies that inform the finished work.

There are some victims that nobody is crying for, so the ground has to cry for them

For her most recent, unrealised piece, Palimpsest, which the artist had hoped to install in an empty city lot when her retrospective opened at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago earlier this year, she spoke to the mothers of local young men who had been killed in shootings. The names of the victims would have been spelled out in droplets of water that slowly seeped up through blocks of concrete, intentionally blurring out other names that had been faintly painted on the stone.

Another work, Plegaria Muda (silent prayer)—comprised of coffin-sized tables stacked with slabs of earth in between and blades of grass growing through the cracks—is based on gang violence in Los Angeles and the killing of civilians in Colombia by soldiers who dressed the corpses to look like guerilla fighters. And a beautifully hand-stitched shroud made from individually preserved rose petals, A Flor de Piel, is dedicated to a Colombian nurse who was tortured and killed by paramilitary troops. The title is an idiom in Spanish, similar to the phrase “wearing your heart on your sleeve”.

The Art Newspaper: From the very beginning, your work has focused on political violence. Have you seen that change at all?

Doris Salcedo: It has remained the same. I think the First World War was the integration of the industrial production of corpses, and we have the idea of the Second World War as the worst moment in history. It hasn’t changed. Right now, it’s just as bad. I don’t have the illusion that art will save lives or diminish the violence, though. I don’t believe in aesthetic redemption. Such a thing is not possible.

We see so many images of violence, and we hear so many reports of death and destruction in the media, that it could be said we’ve become desensitised. Do you think your work helps re-sensitise us?

I hope it does. It adds what is lacking to the media reports, which show us images of bodies, just plain bodies. I don’t like that word. I think we should be talking about subjects, beings; if you want to use the word, soul – not in a religious sense, but of something that is beyond the body. A human being is far more than a body. It’s all the connections, it’s all the relationships, it’s the space they take up in the world—everything that a complete life could give. That aspect is what I hope my work could address.

I devoted myself to making art out of political violence, knowing that it is impossible. I think violent death is obscene, so it is outside representation; it escapes symbolisation altogether. I know what I do is in vain.

Then what do you hope the outcome will be?

I don’t hope for that at all. I always quote Paul Celan, who said that a poem is like a letter you write. You say, ‘Dear…’ and you address that to someone. You write the letter, you put it in a bottle and you throw it in the sea. If that letter reaches the person to whom it has been addressed, that’s OK, but it’s a wild chance. If not, it doesn’t matter; the fact that you addressed the letter is what counts. That is what’s important. So I’m writing that letter with each piece.

Again, I don’t believe this is going to save or change anything. I’m strictly working in the realm of art. And the politics in my work remain within the boundaries of the work—they don’t spill out.

You initially focused on Colombia, but you’ve expanded to include victims of gang violence in Los Angeles, mothers in Chicago whose sons were shot, and displaced people in Turkey. Are there differences in their stories, or is there universality?

There is both. I began with the notion of this pristine, perfect victim from the Holocaust—Anne Frank—an absolutely pure, uncontaminated victim. Later on, as I did more research, that changed. The victim that we experience now is different; it’s someone who can be both the victim and the perpetrator simultaneously. That’s something I learned in Los Angeles. I would see a 14-year-old kid who’s obviously a victim, but at the same time has done some nasty things, because the system placed him there [in that situation]. So there is a grey area that we really need to think about.

That happens in Colombia a lot too. People change sides: one day they go to bed as guerrillas and wake up as right-wing paramilitaries. It’s very fluid. And the more difficult the social conditions, the more fluid that is.

My understanding [of what it means to be a victim] has changed because of the knowledge I acquired in LA. I think my previous understanding was quite naïve, and it has become more complex. And you see that playing out everywhere.

In Palimpsest, you would have included text in your work and named the victims for the first time. Why did you want to do that?

If you have a mother talking about her only son being killed, it is the name and the photo of the child that is ever-present. It is when you pronounce the name that the absence becomes present. So it was unavoidable. I think we are responsible for each death. We have to name them, because it’s the only possibility they have to exist, otherwise they will disappear completely.

Do you still plan to realise that work?

In a different configuration. I think every society has a lot of unmourned victims. Maybe in some other places, there are some other victims that nobody is crying for, so the ground has to cry for them, because nobody else cares. So it will change. I was unable to do it here [in the US]; I couldn’t find the support, but maybe someplace else. Each society has different gaps or voids they don’t want to look into.

This is your first retrospective. Do you feel it is important as an artist to look back on your body of work?

Before, I thought a retrospective should only be posthumous. But in a way, it has been an interesting experience, because it gives me distance and allows me to recognise the work and maybe to change the idea I had behind the piece. And I think that’s richer. Let’s see how I do when I go back to work.

• Doris Salcedo, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, until 12 October, www.guggenheim.org

Digest: Doris Salcedo

Background

Born: Bogotá, Colombia, 1958

Education: Received her BFA from the Universidad de Bogotá Jorge Tadeo Lozano in 1980, before moving to the US, where she gained her MA from New York University in 1984.

Lives and works: Bogotá

Represented by: Alexander and Bonin, New York, and White Cube, London

Milestones Exhibitions: Since the early 1990s, Salcedo has created sculptures in response to cases of political and social violence. Her work has been included in many international biennials, including the Carnegie International (1995), Pittsburgh; Roteiros, 26th Bienal de São Paulo, Brazil (1998); and Trace, Liverpool Biennial of Contemporary Art (1999), Documenta 11, Kassel, Germany (2002), and the Eighth International Istanbul Biennial (2003). In 2007 she created an installation for the Turbine Hall in Tate Modern, London. Shibboleth, a giant crack in the concrete floor that split the space in two, took its name from a word that sets apart one group from a larger society. The crack was filled in, but its “ghost” remains visible.

Awards: She has received numerous prizes, starting with the Penny McCall Foundation Grant (1993), the Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation Grant (1995), the Penny McCall Foundation’s inaugural Ordway Prize (2005) and the Hiroshima Art Prize (2014).