This summer the Los Angeles County Museum of Art is showing Christian Marclay’s The Clock for the sixth time since it acquired the work in 2011. The audience response to the 24-hour collage of film clips has been “tremendous” says a spokeswoman for the institution, who adds that each screening attracts long queues. The reaction in Los Angeles is by no means unique. Since it was made five years ago, The Clock has been seen in more than 20 international museums on four continents and the reaction has nearly always been the same: countless critics have hailed the work as a “masterpiece” and the public has flocked to see it. The film has also been acquired (sometimes jointly) by nine major institutions, including the Tate in London, the Museum of Modern Art in New York and the Centre Pompidou in Paris.

So what is it about The Clock that has made it the most popular work of the past five years? To help answer that question, we compiled a selection of some of the other ubiquitous contemporary works of the past few years – pieces that have been on display around the world almost non-stop since they first left the artist’s studio. Most are immersive, participatory experiences that tap into audiences’ desires to actively engage with contemporary art. It is the level of control visitors to The Clock have that has helped make it so appealing, Marclay says. “It is not a traditional film because it has no beginning or end. You decide when to see it and when to leave it. Your time dictates how much attention you give it. It’s your time that connects you to the screen, the time you are living in now. Unlike a traditional film that takes you out of time, this puts you in synch with the action on the screen. You become a part of the film, you become an actor in it.” All of the works share this characteristic: they are installations you walk into and around, choosing your viewpoint and how you want to see and experience them. Each visit is personal and different.

Perhaps the overriding factor is that, like Marclay’s epic film montage, most of the works on this list use film, sound, music and other theatrical devices to induce emotion. When Janet Cardiff’s Forty Part Motet (2001) was installed at the Metropolitan Museum’s Cloisters outpost in Fort Tryon Park in Manhattan in 2013, the New York Times described the sound installation as “transcendent”, adding that many visitors were in tears. Tate Modern director Chris Dercon told us he cries when he sees and hears brass music, in reference to a work by South African artist William Kentridge. These are works that move us by appealing to all our senses, not just to our intellect. They tap into “a desire for live experience and to connect art to reality, to link all the senses, not only the visual one”, says the Serpentine Galleries’ co-director, Hans Ulrich Obrist, noting that “Margaret Mead [the American cultural anthropologist] said the reason viewers spend so little time in front of works of art is that often they only appeal to the visual sense”. These recent popular works help “liberate time”, Obrist says. All these pieces employ elements of “theatrics”, Dercon notes, adding: “We need performative works more than ever, so we feel alive.”

The popularity of these installations does not lessen their seriousness, say curators. Obrist sees a precedent in the 1950s film-makers of the French New Wave and writers of the Nouveau Roman movement, like the late Alain Robbe-Grillet, who tried “to do work that was advanced and experimental, yet accessible”, because they realised how important it was for the public to connect to art. “I would not use the terms populist, nor entertainment,” says Dercon. He adds that although these works “might be about entertainment”, he has “enjoyed them on many different levels”. Broad, popular appeal and conceptual integrity: the winning formula that helps explain why museums and curators love these pieces—and why we can expect to see them time and again for years to come.

Christian Marclay, The Clock The work: A cinematic timepiece created in 2010, The Clock is a 24-hour montage of thousands of film clips woven together seamlessly, which accurately tells the time. Narrative currents run through the piece, which is technically impressive, exciting and incredibly hypnotic.

Editions: Six

First shown: White Cube, London, 2010

Since seen: In more than 20 major museums and international exhibitions – from Sydney, Yokohama and Jerusalem, to Istanbul, Montreal and Minneapolis, including stints at the Venice Biennale (2011), the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York, the Garage Museum of Contemporary Art in Moscow, the Pompidou in Paris and the Guggenheim in Bilbao.

Current/forthcoming display: The work will be shown at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (Lacma) from 4 July–7 September; a 24-hour screening will be shown on 25 July from 10am.

Acquired: One edition has been jointly acquired by the Tate, the Pompidou and the Israel Museum; another has gone to Lacma; a third edition has been jointly acquired by the National Gallery of Canada and the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston; a fourth has gone to the Kunsthaus Zurich and the LUMA Foundation in Arles; a fifth is a promised gift to MoMA from the collection of Jill and Peter Kraus; and the final edition has been bought by a private collector in the US.

Ai Weiwei, Zodiac Heads The work: Made in 2010, Zodiac Heads is a recreation of 12 bronze animal heads that once adorned Beijing’s Summer Palace but were looted by British and French troops in 1860. Only seven of the originals have been recovered, so the artist reimagined some, such as the dragon and the snake, of which no records survive. The outdoor sculptures are the anomaly in our selection, their popularity underpinned by the powerful narrative of an imprisoned artist at the height of his game.

Editions: Six large editions in bronze for outdoor display, plus two artist’s proofs. There are eight smaller gilded editions for indoor display, plus four artist’s proofs.

Bronze version first shown: São Paulo Biennale, 2010

Since seen: Since May 2011, the bronze editions have been on an ongoing world tour organised by AW Asia in New York, an organisation that promotes contemporary art from China. The tour started at the Pulitzer Fountain at Grand Army Plaza in New York and continued to the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington DC; the Los Angeles County Museum of Art; Somerset House in London and venues in Taipei, Mexico City, Kiev and Toronto, among many others.

Current display: Editions of the bronze Zodiac Heads are on display at Princeton University in New Jersey (until December 2016); outside Chicago’s Alder Planetarium (until September) and at the National Museum of Wildlife Art in Jackson, Wyoming (until October).

Acquired: The collector Budi Tek has bought an edition of the bronze Zodiac Heads to display in the art park he is constructing in Bali, due to open in 2017.

Janet Cardiff, The Forty Part Motet The work: Made in 2001, the piece is a recording of Tudor composer Thomas Tallis’s 1575 choral piece, Spem in Alium, played on 40 hi-fi speakers, each one transmitting the voice of a single singer. The speakers are arranged in a large oval so visitors can hear individual voices or move into the centre of the piece to listen to the ensemble.

Editions: Three, plus one artist’s proof

First shown: Salisbury Cathedral Cloisters, Salisbury, UK, 2001

Since seen: In around 40 venues in Europe and North America, including Castello di Rivoli in Turin, the Whitechapel in London and the Moderna Museet in Stockholm. It is the only work in our selection to have been shown in New York both at MoMA (once in its main building and twice at its PS1 outpost) and at the Metropolitan Museum (in its Cloisters outpost in 2013).

Current/forthcoming display: Included in Reverberations at Rödasten Konsthall in Gothenburg, Sweden (until 23 August) and on show in Arles at Luma’s Parc des Ateliers (opens 6 July). It goes on show at the Fort Mason Center in San Francisco from 14 November–18 January 2016.

Acquired: MoMA in New York, the National Gallery of Canada in Ottowa, and the Kramlich Collection in San Francisco which has promised it as a fractional gift to Tate in London.

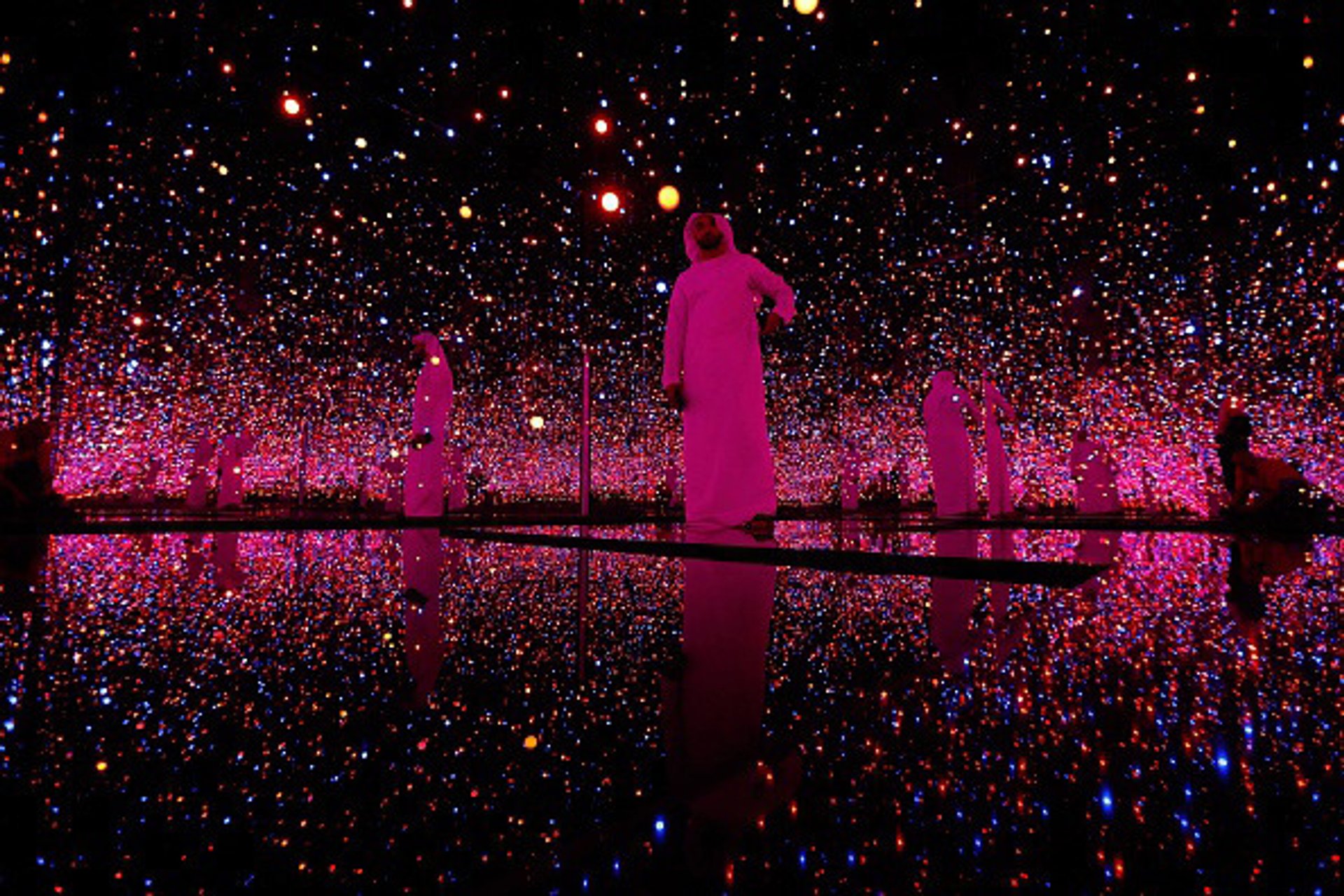

Yayoi Kusama, Infinity Rooms (sometimes known as Mirror Rooms) The work: A small room is transformed into a meditation on the infinite through the use of mirrors, hundreds of light bulbs or LED lights, with their endless reflections, and sometimes water on the ground, which together create the illusion of endless space. Yayoi Kusama has made 18 different versions of her Infinity Rooms.

Her first was Infinity Mirrored Room–Phalli’s Field (1965), in which the floor was covered with sewn stuffed fabric shapes covered in polka dots. The work was remade in 1998. The second version, Infinity Mirrored Room-Love Forever, was made in 1966 and remade in 1994. Mirror Room (Pumpkin), a yellow room covered in black dots, dates to 1991. Then came Infinity Mirrored Room–Love Forever in 1996, which featured geometric patterns of light bulbs across the entire ceiling, and Repetitive Vision, which included mannequins. Dots Obsession from 1998 was remade in 2008.

In 2001 Kusama began to work with darkened rooms such as Infinity Mirrored Room–Glowing Lights in Shinano. In 2002 she introduced water to her rooms with Fireflies on the Water and Soul Under the Moon, but also made a version without called Infinity Mirrored Room, Rain in Early Spring. In 2005 she used an LED lighting system for the first time in You Who Are Getting Obliterated in the Dancing Swarm of Fireflies. In 2008 she made two further versions, one with light bulbs (Dots Obsession–Infinity Mirrored Room) and one with an LED lighting system and water (Infinity Mirrored Room–Gleaming Lights of the Souls).

The artist’s next few rooms were all darkened spaces with LED lighting and water on the ground: Aftermath of Obliteration of Eternity (2009), Infinity Mirrored Room–Filled with the Brilliance of Life (2011) and Infinity Mirrored Room–The Souls of Millions of Light Years Away (2013). In 2013 she also introduced speakers and sound in another room entitled Love is Calling. Her most recent version is Infinity Mirrored Room–Brilliance of the Souls (2014).

First shown: The first Infinity Room was shown at the Castellane Gallery in New York in 1965, in a solo exhibition, Floor Show.

Since seen: The rooms have been shown around the world in major institutions including Tate Modern in London, the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York, the Guggenheim Abu Dhabi, the Pompidou Centre in Paris, the Reina Sofia in Madrid and the National Museum of Art in Osaka. An Infinity Room—Infinity Mirrored Room Filled with the Brilliance of Life (2008)—was included in the recent Kusama show which toured South America, stopping at Malba Buenos Aires, CCBB Rio, CCBB Brasilia, Tomie Ohtake Institute São Paolo, and the Museo Rufino Tamayo in Mexico.

Current/forthcoming display: Infinity Mirrored Room–The Souls of Millions of Light Years Away (2013) is on show at the Garage Museum of Contemporary Art in Moscow as part of Yayoi Kusama: Infinity Theory (until 9 August). Another edition will be in the inaugural display of the Broad Art Foundation when it opens its museum in Los Angeles on 20 September. Gleaming Lights of the Souls (2008) will go on view at the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art in Humlebaek, Denmark (17 September–24 January 2016).

Acquired: Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam (1965/98 version); Fondation Louis Vuitton, Paris (1965/98 version); Hara Museum of Contemporary Art, Tokyo (1991 version); Mattress Factory Pittsburgh (Repetitive Vision, 1996, is on long-term loan); Matsumoto City Museum of Art, Japan (2001 version); Whitney Museum, New York (Fireflies on the Water, 2002); Queensland Art Gallery, Gallery of Modern Art, Brisbane (Soul Under the Moon, 2002); Phoenix Art Museum (2005 version); Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, Denmark (Gleaming Lights of the Souls, 2008); Guggenheim Abu Dhabi (2011 version); Garage Museum of Contemporary Art, Moscow (Infinity Mirrored Room–The Souls of Millions of Light Years Away, 2013); and the Broad Art Foundation, Los Angeles (Infinity Mirrored Room–The Souls of Millions of Light Years Away, 2013).

Isaac Julien, Ten Thousand Waves The work: A nine-screen video installation made in 2010, shot in China with the actress Maggie Cheung, Ten Thousand Waves is a poetic story of migrations across continents, such as those undertaken by the 21 Chinese cockle-pickers who drowned at Morecambe Bay in north-west England in 2004.

Editions: Six, plus one artist’s proof

First shown: Sydney Biennale, 2010

Since seen: At the Museum of Modern Art in New York, the Institute of Contemporary Art in Boston, the Hayward Gallery in London and at venues in Shanghai, Seoul, Helsinki, Oslo, Miami, Munich, São Paulo and San Diego, among others.

Current/forthcoming display: Included in Harmony and Transition: Reflecting Chinese Landscapes at Marta Herford in Germany (until 4 October). The installation will occupy the nine-storey central space for monumental installations at Zeitz Museum of Contemporary Art Africa in Cape Town, when the museum opens in 2017.

Acquired: The Museum of Modern Art in New York, Nasjonalmuseet for Kunst in Oslo, M+ in Hong Kong, Zeitz MoCAA in Cape Town, Fondation Louis Vuitton in Paris and Museum Brandhorst in Munich.

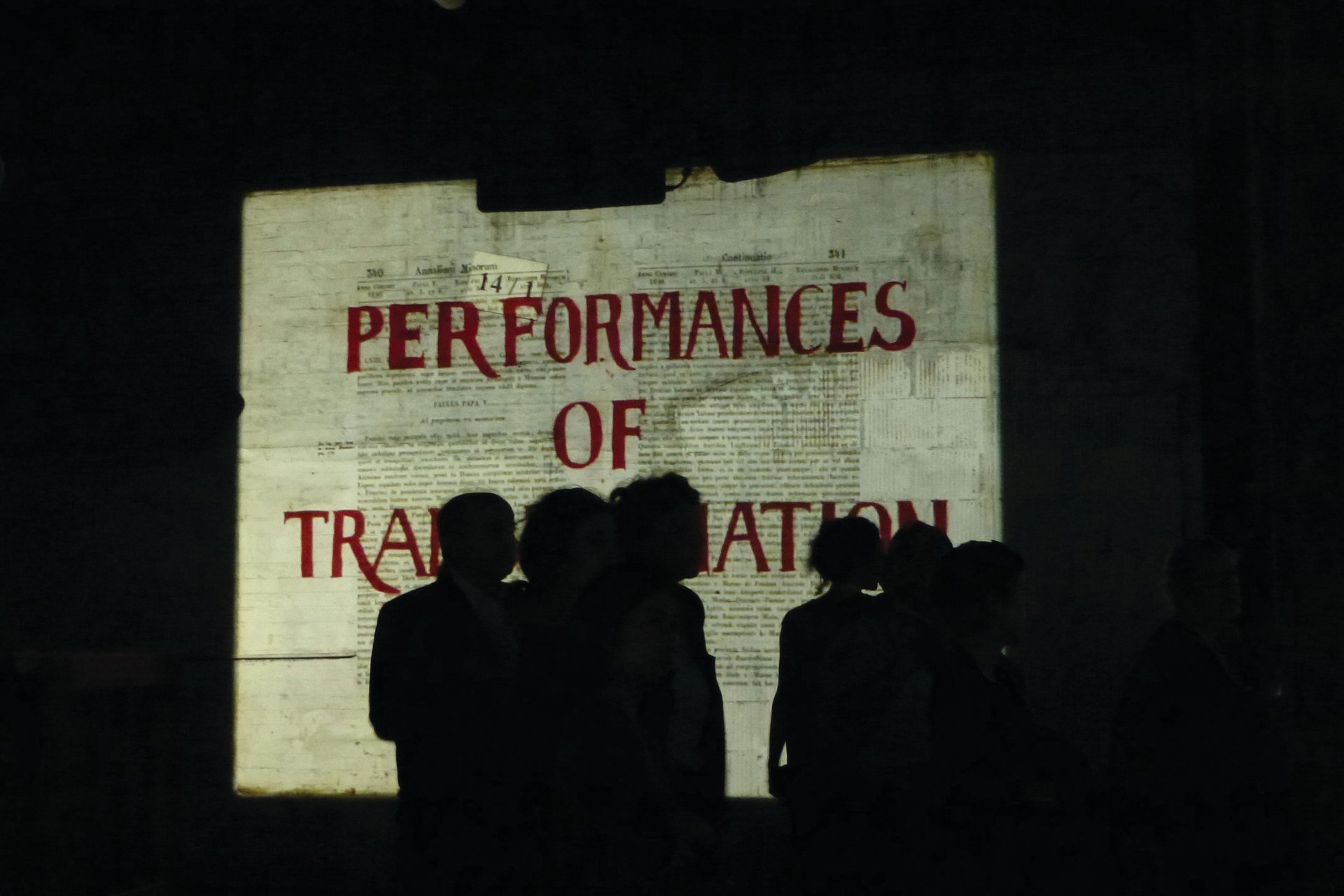

William Kentridge, The Refusal of Time The work: A five-channel video installation exploring the relativity of time and the legacies of colonialism, featuring film clips, stop-motion animations, a wooden machine with pumping pistons in the centre of the display, and a score by Philip Miller to create a complex, all-encompassing environment. The installation, which was made in 2012, is a collaboration with Peter L. Galison, a professor of the history of science and physics at Harvard University in Massachusetts.

Editions: Six

First shown: Commissioned by Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev for Documenta 13 in Kassel in 2012.

Since seen: At the Metropolitan Museum, New York; the National Gallery, Cape Town; the Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston; the Perth Institute of Contemporary Art, Australia, the City Gallery, Wellington, New Zealand, and MAXXI, Rome.

Current display: The work is included in William Kentridge: Notes Towards a Model Opera, currently at the Ullens Center for Contemporary Art in Beijing (until 30 August). The show travels to the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art in Seoul.

Acquired: Jointly acquired by the Metropolitan Museum in New York and the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. Another edition has been bought by the Art Gallery of Western Australia and a third is in a private US collection.