Francis Bacon and the Masters at the Sainsbury Centre for the Visual Arts in Norwich is a solemn gimmick, which has been done before (at the Kunsthistorichesmuseum in Vienna, 12 years ago, with Francis Bacon and the Tradition of Art). The idea—which it is hard to know what to do with—is to put real works from the past next to real works by Bacon to demonstrate that he is connected to great achievements. He certainly said in interviews that he was impressed by the art of the past, but shows like this uncomfortably raise the question of what he actually meant.

The spectrum of positions adopted by the British press has so far gone from Taking The Bait to The Scales Fell From My Eyes. One critic, after making the trip to Norwich (three hours from London), found Bacon surprisingly sculptural when she saw a painting by him in front of a sculpture and surprisingly Matissean when one was next to a Matisse. Another went all moody and threatened readers that he “may never admire Bacon again.” A third scratched his head at the challenge of spotting a resemblance between a painting by Bacon of a woman and a Roman bust of a bearded man. When he encountered paintings by Ingres, Derain and Bacon all sharing the same colour scheme, he thought it was “a snappy synopsis of art history.”

The show is exciting from a design point of view, both in terms of the exhibition environment produced by Andres Ros Soto—who is young and based in Mexico, and produces furniture and rugs, as Bacon himself did in his 20s—and the undoubted qualities of Bacon as a painter-designer. This aspect of him is a tricky issue.

Bacon is a great artist of certain things, and it is definitely possible to be seduced by him. Abandoned beginnings on large canvases near the entrance to the show, dating from the years just before his death in 1992, immediately convey what makes him good. He commands that space with a fluent, fast, surprising line. Then, as you go through the rest of the show, you see juxtapositions of old and new that work as something like stage effects. And then, further in still, you see innumerable middling work by Bacon with art by the Greats where you are not sure how you are supposed to respond to either. This is because any dialogue with artists either pre-Modern or Modern (Picasso and suchlike) is clearly seen to be hopeful and fantastical rather than substantial.

Regardless of whether they are top-drawer examples, the Bacon works here are, as ever, their own thing. Bits and pieces of enjoyably macabre incidents are conjured up out of structurally incoherent paint swipes and act as focus points within overall decorative arrangements featuring Matissean expanses of flat colour. But there are fleeting connections that the show wants you to notice, of shapes and lines, poses, even colours that, absurd as they often are (a green Bacon and, er, a green Matisse?), nevertheless supply clues about Bacon’s real skills. Unfortunately, these go against the thesis of the show because the main one is his peculiar ability to conjure something genuinely impressive out of very little. Overall broad unity full of calm abstraction counters internal miasmic slipperiness.

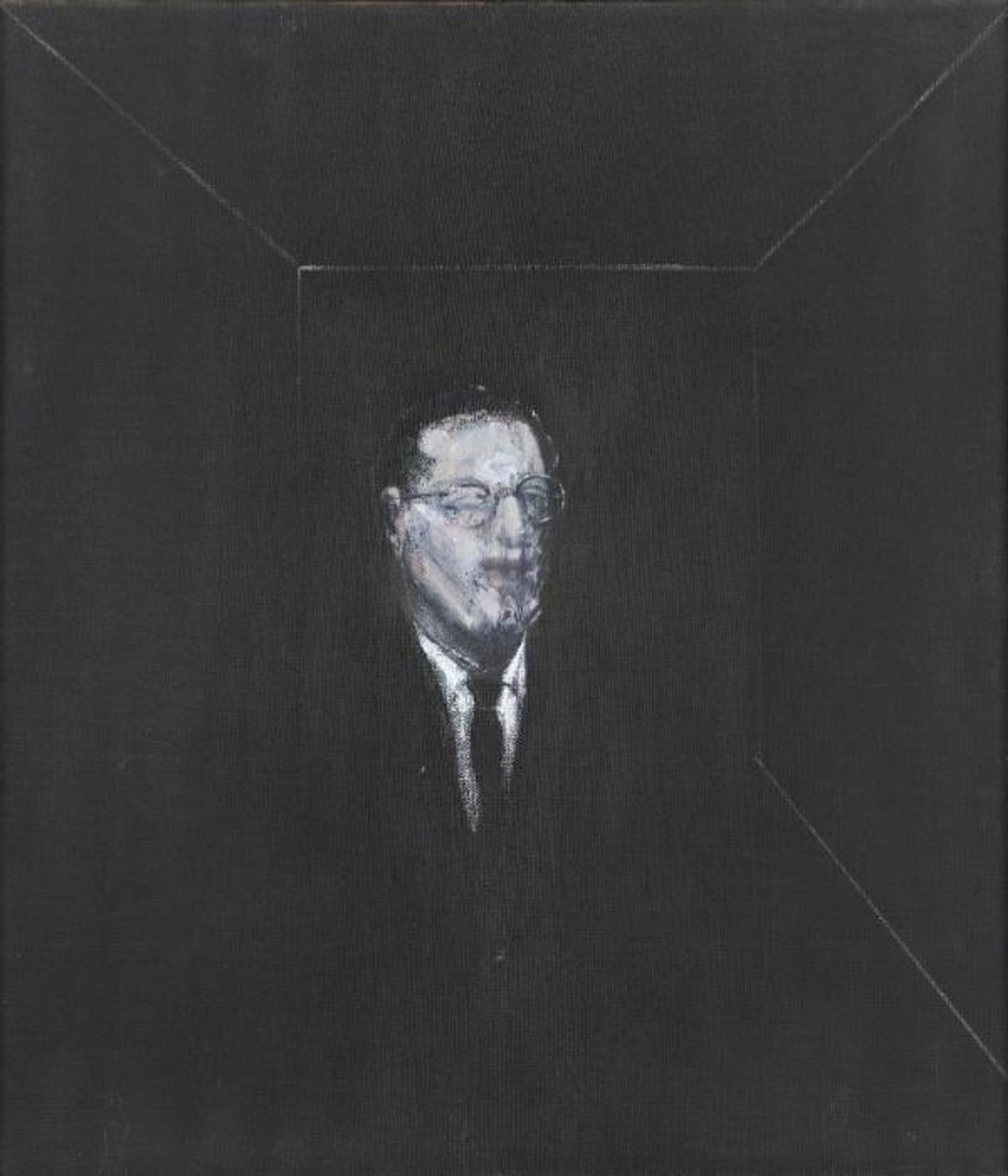

A highlight is Soto’s face-off between ancient Egyptian funerary masks and early 1950s portraits by Bacon of Lisa Sainsbury. In a play of intermingling blurred reflections caused by the antique art being displayed behind a wall of glass in a dark space, and Bacon's paintings being glazed (as they always are), heads by him and heads from two and even three thousand years ago seem to exist, albeit in slipping glimpses only, as objects that are different but related, and beautifully sympathetic. It's a bit unreal but it's a marvellous spectacle. Both kinds of heads, ancient-Classical and modern-Expressionist, are stretched vertically, like monuments; with the antique objects it is their tall hats that cause this distortion, and with Bacon’s portraits it is because Lisa Sainsbury’s head and neck are picked out as a single very pale form against a black void.

Throughout, there are mirroring moments that seem exciting if you do not think or look hard. Dud juxtapositions include a magnificent Cubist female nude by Picasso from 1909, its arrangement achieved through part-to-part painterly invention, next to the famous painting by Bacon of Isabel Rawsthorne owned by Tate, that is all swoosh. It is fine on its own but ridiculous next to Picasso. The same Surrealism, or meeting of things that have nothing to do with each other, obtains when we are treated to the sight of Christ carrying the Cross painted by Titian in the 1560s, and the painting by Bacon called Crucifixion (1933). The latter's feathery-edged white oval in a void, which has undeniable fascination seen on its own, becomes—in relation to the delicate textures and mighty architectonic structure that Titian puts together—less Theatre of Cruelty than laughable doodle.

The message of Soto’s design is that Bacon is not in a dialogue with any masters, but with us: with our modern cultural moment and our expectations of art. Interestingly, in the same space as the Egyptian display, we see letters from Bacon to Robert and Lisa Sainsbury, his early supporters. It is possible to gain the impression from his begging for money that he hated himself. They are not like Vincent van Gogh’s letters, because the visual associations are so opposite: unlike van Gogh, Bacon’s paintings are all falling apart internally. The psychology of these letters to the Sainsburys seems to be that by getting affirmation socially, he could convince himself he was getting it for artistic achievements that even he thought might be dubious.

That’s why he’s our guy. When the past becomes the content of today’s art, as it frequently does, whether it is painters or artists using any media at all, it is not through engagement with traditions of making that lasted for hundreds of years but via fragmentary ironic sampling. Artists manufacturing their wares for biennales know that only distanced content, referred to by signs, is what is wanted now. (As it says in a funny book for young people about art, published 20 years ago: “Bacon is all short cuts to deep content”).

Bacon might have had any object or set of them in mind when he told interviewers over the years that he considered Egyptian art to be “the best there’s ever been”, but a curatorial/exhibition design move responding to this preference mesmerises the viewer. You are drawn into a semblance of continuity simply by the pleasure of the way it is presented. Less overwhelmingly, but still with a certain occasional effectiveness, Soto makes Michelangelo, Gauguin, Ingres, Velazquez, Rembrandt and Roman art, all seem nothing like Bacon in essence but infinitely capable of being like him as assemblies of so many parts. These fugitive likenesses are fun but say too much about the relationship in the first place between him and the “masters,” getting something over quick that someone would be sure to think was important.

Matthew Collings is an artist, writer and TV broadcaster.

Francis Bacon and the Masters, Sainsbury Centre for the Visual Arts, until 26 July

Correction: An earlier version of this article stated that Francis Bacon sent letters to Lisa and Timothy Sainsbury. In fact, the letters went to Lisa and Robert Sainsbury.