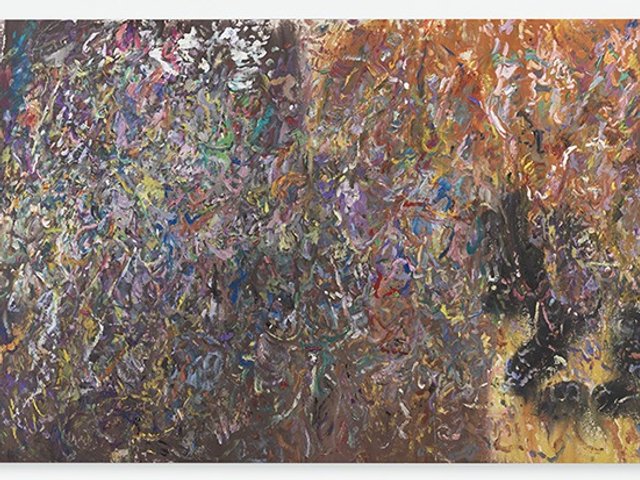

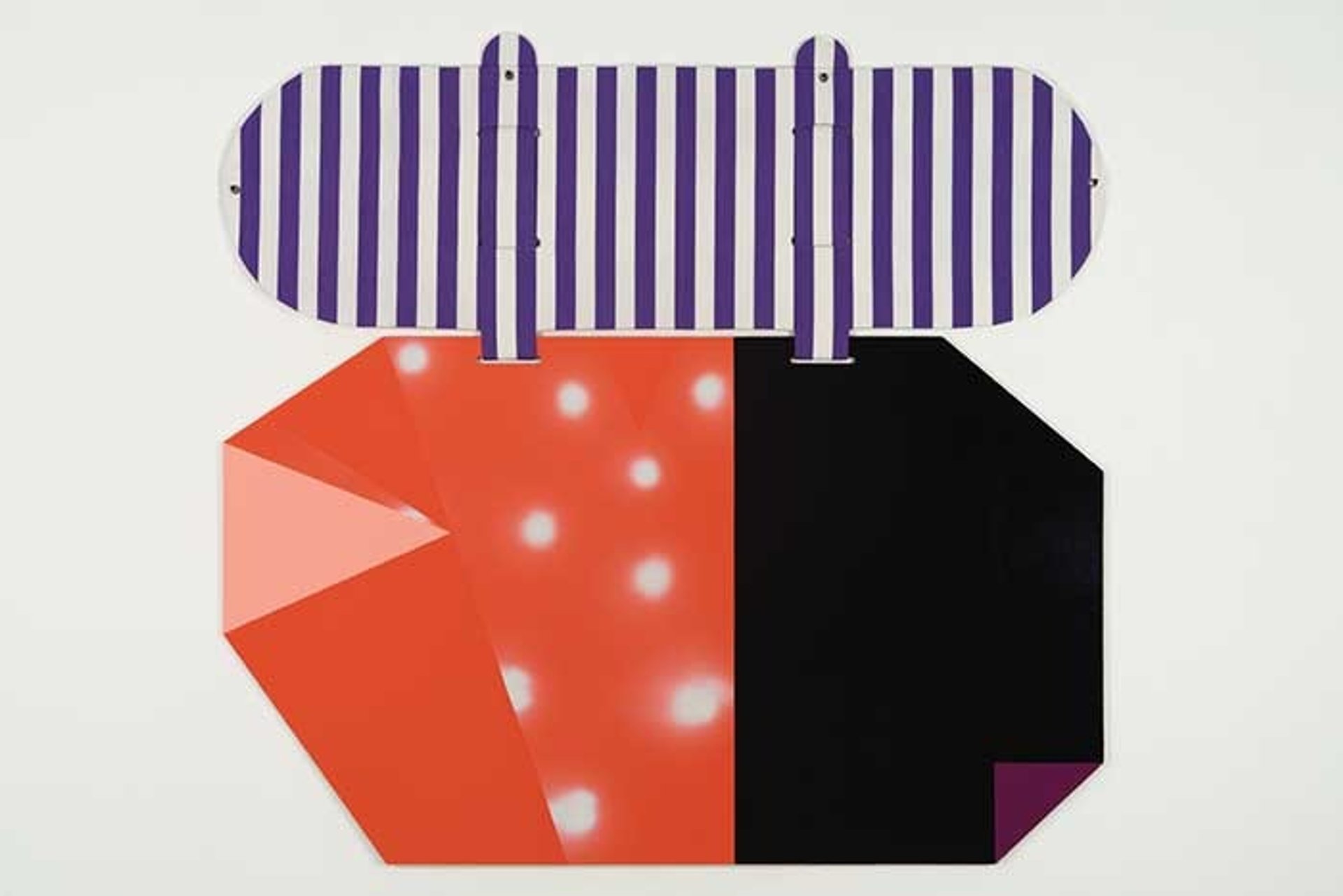

Painting is back in style. At the Kunstmuseum Bonn, the exhibition New York Painting (until 30 August) looks at the work of 11 contemporary artists based in the city, including Eddie Martinez and Antek Walczak, who are part of the medium’s “recent return to cultural acclaim,” in the words of the art historian Richard Shiff. Yet critics, who often insist on comprehensiveness, have failed to take into account the raw power of individual pictures, Shiff argues. In the below essay, which is an adapted version of his catalogue essay for the exhibition, Shiff surveys the terrain of criticism and explains why critics have been remiss.

Repetition and cliché infect art criticism. The art historian Thierry de Duve noted an irony in 2003: “About once every five years, the death of painting is announced, invariably followed by the news of its resurrection.”

Like history, criticism is subject to optics—that is, perspective. Critics once opposed photography to painting, as if the two media were representative of antithetical psychologies and social orders. This perspective lies within the penumbra of Walter Benjamin, who associated painting with focused concentration and photography and film with disruptive distraction. But photography, film and video are productive technological aids for painters, as are copiers and computers. Few of us today balk at the juxtaposition of hand-drawing and digital printing. Each can be manipulated to resemble the other—or not. It remains an artist’s choice, refined or sometimes reversed in response to immediate sensation. Critics, with their comprehensive concepts, shield themselves from such experiential disorder.

The problem is optical: two parties, critics and artists, look past each other with incompatible expectations. Art critics often typecast painters as committed “modernists” and, what is worse, “formalists.” But even Clement Greenberg, who has been maligned for his rigid evaluative standards, warned of applying conceptual order to aesthetic judgment. Few listened when he said it: “There’s no theory. No morality.” Feeling comes first. When critics argue that any emotional or intellectual position must always derive from an existing cultural construct, they beg the question, and dismiss the feeling of their own experiences.

Consider this common, usually unchallenged, notion: photography constitutes “a phenomenon from which painting has been in retreat since the mid-19th century”. This is Douglas Crimp’s phrasing from 1981, put at the service of the argument that painting had died. Yes, photography depersonalizes imagery. But so does much modern painting. To avoid “that hand touch,” as he phrased it, Robert Mangold used sprayers and rollers. Mary Heilmann developed a slapdash technique, “a freeform, unstretched kind of painting work,” as she has said, so that her hand might be anyone’s. David Reed arranged paintings in the manner of film strips, to be animated by an anonymous viewer’s mobility. Jack Whitten combed, raked, or swept his way across paint layers: “The idea was to construct a non-relational painting by extending a single gesture to encompass the entire picture plane,” he once said. “The analogy, symbolically, was to photography.” Thoughts of impersonal, mechanistic photography have motivated many innovative painters. The two media are not at odds unless willfully put there.

A social critique like Crimp’s operates within limited optics. An artist’s need to engage in hand-work raises issues apart from the totemic value of handmade objects as markers of cultural prestige and economic status. The notion that humans have always had the desire to make paintings should not be dismissed as an arbitrary element of modernist mythology, as Crimp’s account insists. Academicised critical formulations—whether they are dialectical, historicist or determinist—have no bearing on the human need for immersion in physical acts of creation.

Clichéd metaphors

Corpse, zombie, vampire, ghost, mourning and cannibalization: these are among the clichéd metaphors attached to painting. In his 1984 article Postmodernism, or the Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism, the cultural critic Fredric Jameson assessed the society that had nurtured walking-dead media. His analysis derived from the prevailing theoretical discourse—the writings of Benjamin along with other Europeans, such as Henri Lefebvre and Guy Debord—only to re-enter the critical conversation as an authoritative template for North Americans. Those who argued the case for postmodernism in the 1980s, with its strategies of pastiche and appropriation, seemed to act their theory out; they cited Jameson frequently, repeating his array of examples and mimicking his phrasing.

Postmodernism signaled the collapse of the modernist ideology and the dissolution of modernism’s foundations in authenticity, individual subjectivity and emotional expressiveness. Jameson noted “the waning of affect ... the imitation of dead styles ... the random cannibalization of all the styles of the past.” Such strategies and effects served a consumer’s “appetite for a world transformed into sheer images of itself”—life removed from living, feeding on the corpse of life. Gone was the integral subject, the authentic experience, the expressive self. Gone was easel painting.

The emerging consensus already troubled Max Kozloff in 1975: “A whole mode, painting, has been dropped gradually from avant-garde writing.” Arthur Danto added a wrinkle in 1993: “It was ... ‘handmade’ art that was dead ... the easel picture.” Despite painting’s recent return to critical acclaim—or marketplace enthusiasm—metaphors of its demise persist, as if this art, when revived, were still half-dead, an aura lacking a body. As David Geers wrote in 2012: “[We] re-live a myth of a ‘wild,’ unmediated subjectivity welded inextricably to the primal medium of paint ... nostalgic and mystified.”

Today, painting lives on while the critical terms pale. In 2014, Laura Hoptman organised an exhibition of recent painting, The Forever Now, for the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Her ingenious title generated unwanted echoes of Thomas Lawson’s vilification of Barbara Rose’s analogous exhibition at New York University’s Grey Art Gallery, American Painting: The Eighties, staged in 1979: “a corpse made up to look forever young.” At the time, Rose’s artists—among them, Elizabeth Murray, Mark Lancaster and Mark Schlesinger—were condemned wholesale, despite the variety of their methods. They shared only the misadventure of painting. To greet an exhibition like Rose’s or Hoptman’s with bias for or against the medium is to miss all the informative nuances. When critics harp on rising commercial values or restrict their analysis to social critique, they deny life to the medium, so that painting appears vampiric. But such a response derives from critical concepts that are projected onto the art. It ignores the work’s manifest energy.

Generating generalities

The politics of art keeps generating generalities. Within American universities, the case against painting has hinged on the belief that Western culture is morally bankrupt; that it is inherently sexist, racist, colonialist, imperialist and authoritarian. Because Western nations sponsor museums packed with paintings—many of which are commissioned or owned by oligarchs and dictatorial leaders—the medium can appear complicit with corruption and oppression. Yet such induction is faulty: an artist may be complicit, but painting itself exercises no agency.

In 1974, Rose warned against “the skepticism of any criticism based on distinctions of quality.” As she wrote: “weakening public trust in art may as easily pave the way to fascist counterrevolution, for a mass culture in the service of totalitarian ideals.” When Crimp quoted from Rose’s essay in 1981, he actively excised that sentence. Her overt fear of “fascist counterrevolution” would have muddled his argument, which required opposing his “cultural” and “historical” interest to her “natural” and “mythical” aestheticism.

According to Crimp, Rose failed as a critic because she never challenged “the myths of high art” or “the artist as unique creator.” If these “myths” continued to inform Rose’s optics, we merely witness a conflict of systems of belief. Neither Crimp nor Rose is more ideologically progressive (although Crimp attacked Rose’s values as regressive, implying that history had a trajectory and had left both her and the medium of painting behind).

To call Rose’s belief a myth, as Crimp did, is either trivial or inherently extreme—extreme if it implies that one’s own belief is not also a myth. All beliefs, which instigate aesthetic strategies, amount to myths; if not, they would be facts or laws of nature. But even laws of nature are subject to irregularity and exceptions to their presumed invariability; they are also therefore mythical. The “death of painting,” as a widely held theory that its adherents fail to question, is another myth. We cannot escape our myths simply by accepting alternative beliefs. To suppress general beliefs and principles altogether would be more effective—a state worth seeking, even if impossible to attain.

Artists devoted to painting believe in it, but they also doubt their belief. Their doubt opens painting, as well as its artists, to living.

Richard Shiff is professor and the Effie Marie Cain Regents Chair in Art at the University of Texas at Austin.