The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York hosted a private reception in 2009 for the Manhattan-based, Indian-born art dealer Subhash Kapoor to honour his donation of dozens of Indian drawings. But even as he was being feted, the illegitimate side of Kapoor’s success was beginning to come to light.

The reception marked a high point for Kapoor who had built his Madison Avenue showroom, Art of the Past, into a leading source of Asian art for museums and collectors around the world. Kapoor had carefully cultivated that status with donations of Indian paintings and the sale of rare South and South-east Asian antiquities to leading museums including the Met, which today has 81 objects from the dealer in its collection.

Months before the Met event, US federal authorities seized a shipment of stolen antiquities sent to Kapoor by sources in India, according to what appears to be a signed confession that Kapoor made in 2012. Additional shipments to Kapoor would be stopped repeatedly over the following years as investigators in the US and India quietly built criminal cases against the dealer, records and interviews show.

Kapoor was arrested on an Interpol warrant during a business trip to Germany in October 2011 and extradited to India, where today he is awaiting criminal trial accused of trafficking in stolen art.

The Manhattan District Attorney’s office plans to extradite Kapoor for trial in the US once the Indian process has concluded. It has already won convictions against three of Kapoor’s associates: his gallery manager, Aaron Freeman, Kapoor’s long-time girlfriend Selina Mohamed and Kapoor’s sister Sushma Sareen.

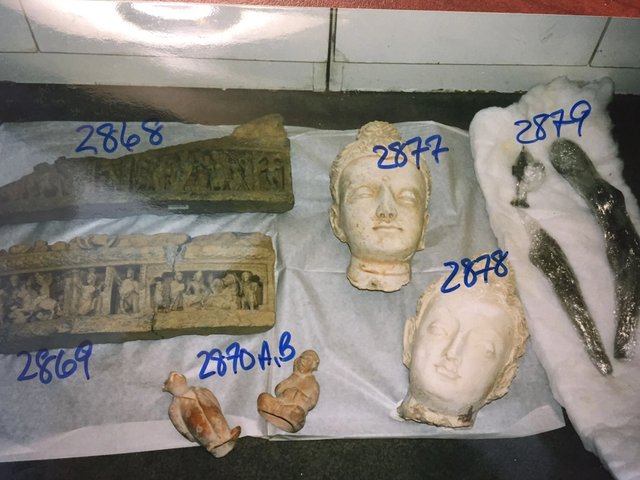

The US investigation, dubbed Operation Hidden Idol, has also led to what has been described as the largest antiquities seizure in US history: some 2,600 objects valued at more than $100m have been taken from Kapoor’s properties since 2012.

In April, the Manhattan district attorney filed papers describing the objects as the proceeds of crime and began the legal process of having them returned to India. But the massive haul represents only the inventory Kapoor had on hand when arrested. Since the 1980s Kapoor has sold or donated thousands more objects. To find them, federal agents are combing through years of Kapoor’s business records, emails and catalogues, building a picture of his global supply network, which stretched from the tribal regions of Pakistan, the jungles of Cambodia and the temples of southern India to collections around the world. Photographs in his archives show objects allegedly in the process of being smuggled.

“We’ll be actively pursuing Kapoor pieces well after my career is over,” says Brenton Easter, the lead agent on the investigation being run by Immigration and Customs Enforcement’s Homeland Security Investigations team. “That’s how much material is out there.”

The Kapoor case once again highlights lacklustre due diligence employed by museums that collect ancient art: few at the time questioned the thinly documented ownership histories that Kapoor’s staff have admitted creating.

Kapoor’s confession

In his 2012 confession to an Indian magistrate, Kapoor, then 63, described his life in the antiquities trade, which started as a boy in his father’s Delhi antiques shop. Kapoor moved to New York in his twenties, became a US citizen in 1980 and started his Manhattan gallery in 1987. In 2003, he created Nimbus Import Export Inc “for trading in cultural antiques”.

To find suppliers, Kapoor said he visited Indonesia, Thailand, Cambodia, Vietnam, Hong Kong, Pakistan, Sri Lanka and his native India. It was in the southern Indian city of Chennai during a visit in 2005 that he met Sanjivi Asokan, who allegedly put him in touch with local temple thieves. They “became my business contacts, commission agents and dealers for whom I promised lucrative returns”, Kapoor said.

Kapoor visited several temples with the thieves and identified the tenth-century Chola-era bronzes that would bring top prices on the market, he said. The thieves eventually stole 18 of the bronzes and sent Kapoor images of them. In return, he wired them hundreds of thousands of dollars “since they are required to be burgled [sic] by breaking open temples, transportation to [Ashokan’s] Arcelia Gallery, dull polishing, creating false documents through false letter heads and forging false signatures” before being smuggled out of India in a shipment mixed with modern handicrafts.

The shipments were sent through contacts in Hong Kong and London before arriving in the US, where Kapoor said he and his staff “created false provenance” for the objects and sold them for “huge sums”.

The most common cover story they used was that objects had come from the family collection of Kapoor’s girlfriend, Selina Mohammed. Another favourite was a “private collector” named Raj Mehgoug. At the time, records show, Mehgoug lived in a modest duplex outside Philadelphia.

Kapoor’s New York attorney in New York declined to comment on the confession or his legal case, and his attorneys in India did not respond to requests for comment. It is unclear whether Kapoor and his lawyers accept that the confession, which appears to bear his signature, is legitimate or will be admissible in his forthcoming trial, which has been repeatedly delayed.

Museums react

In the wake of Kapoor’s arrest, museums around the world have been hard pressed to explain their dealings with him. Nowhere has the impact of the case been felt more deeply than Australia.

In 2008, the National Gallery of Australia (NGA) paid Kapoor $5m for a bronze Dancing Shiva that had been stolen from a temple in Tamil Nadu. It was one of 21 objects the NGA purchased from Kapoor for more than $8m in total. The museum ignored the advice of its attorney, who warned that the Shiva’s provenance was “at best, thin”.

Revelations about more than two-dozen suspect Kapoor objects at the NGA and the Art Gallery of New South Wales (AGNSW) were initially met with scepticism. But as press accounts brought to light evidence of forged ownership histories and damning smuggler photos, the museums were forced to respond.

The NGA announced an internal investigation led by its then director, Ronald Radford, who had pushed for the Kapoor acquisitions. The AGNSW took a different path, publicly releasing provenance documents supplied by Kapoor. Soon after, Indian blogger Vijay Kumar identified the temple from which the sculpture had been stolen.

“If there’s an object in question, it seems appropriate to allow to the public to see those records,” says Michael Brand, the AGNSW’s director. “There’s clearly a benefit in sharing the information.” But most museums have not followed his lead.

In September 2014, the Australian prime minister Tony Abbott personally delivered two of the Kapoor objects to Indian prime minister Narendra Modi. Radford, the director of the NGA, retired soon afterwards.

Duncan Chappell, an art crime expert and a visiting scholar at Queen Mary, University of London, says: “This fiasco has resulted in a far reaching appraisal by Australian public galleries of their acquisition policies and the prompt implementation of new tougher practices and procedures.” Chappell and Brand draw parallels between the impact of the Kapoor case and the Italian investigation of a looting network run by Giacomo Medici, which a decade ago led to the return of hundreds of Classical pieces from US museums and the adoption of more stringent acquisition policies.

These policies are under scrutiny again as the Kapoor case has now shifted to US museums.

In October 2014, The Toledo Museum of Art agreed to return a bronze Ganesh that Indian authorities identified as stolen in 2009. The museum is deliberating on the fate of more than 60 other Kapoor objects, including a sculpture of Varaha Rescuing the Earth bought for $225,000 in 2001. A museum spokeswoman says as the piece is subject to the ongoing federal investigation it cannot comment on it at this time. Its website states that it suspects the sculpture’s provenance was fabricated and has contacted Indian authorities.

In April, the Honolulu Museum of Art gave up seven Kapoor works, and the Peabody Essex Museum in Massachusetts handed over a Kapoor painting that came with a false provenance to the Department of Homeland Security. Other museums have opted to hunker down and declined to release copies of the provenance documents provided by Kapoor.

“The Met is and always has been fully prepared to co-operate,” says a spokesman. Meanwhile, a spokeswoman for the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, which has 62 Kapoor objects, says: “We’d be willing to return any objects should we receive a request.”