It is more than 40 years since the scholarly study of Victorian architecture began to generate a series of detailed studies of the work of the leading architects of the Victorian era. Paul Thompson’s 1971 book on William Butterfield led the way. The appeal of Butterfield extended, in fact, beyond the ranks of the Victorian Society—Ian Nairn had famously enthused about All Saints, Margaret Street, London, a building that reputedly influenced the work of the young James Stirling. High Victorian Gothic, forceful and angular, appealed to the New Brutalist generation.

George Frederick Bodley (1827-1907), in contrast, had long been depicted as a figure irredeemably rooted in the lost world of late Victorian Anglicanism. For H.S. Goodhart-Rendel, writing in 1953, his work, predominantly though not exclusively ecclesiastical, “satisfied completely the aspirations of those who believed that the road to national sanctity lay through the older public schools and universities, guarded by Anglican scholarship from the intruding errors of Geneva or of Rome”. Bodley’s earlier, muscular Gothic—exemplified by his church at Selsley, Gloucestershire (1861-62)—was one thing; his later work, refined and thoroughly English in inspiration, another. Pevsner declared Bodley’s church at Hoar Cross “essentially derivative”, while Nairn complained of Bodley’s “weary, cultured voice”. For other critics, the refinement which characterised Bodley’s mature work verged on preciousness.

Early in his career, Bodley had been associated with Morris and the Pre-Raphaelites, but he had no truck with the Arts and Crafts Movement and its championing of the individual designer and craftsman. Seeking control over every detail of his church interiors, he came to rely on firms content to bend to his over-riding aesthetic: Watts & Co for textiles, and Burlison & Grylls for stained glass, for example. Yet the Arts and Crafts designer and Bodley pupil C.R. Ashbee wrote that Bodley’s office was a place where “art is studied in about a sacred way as it can be”.

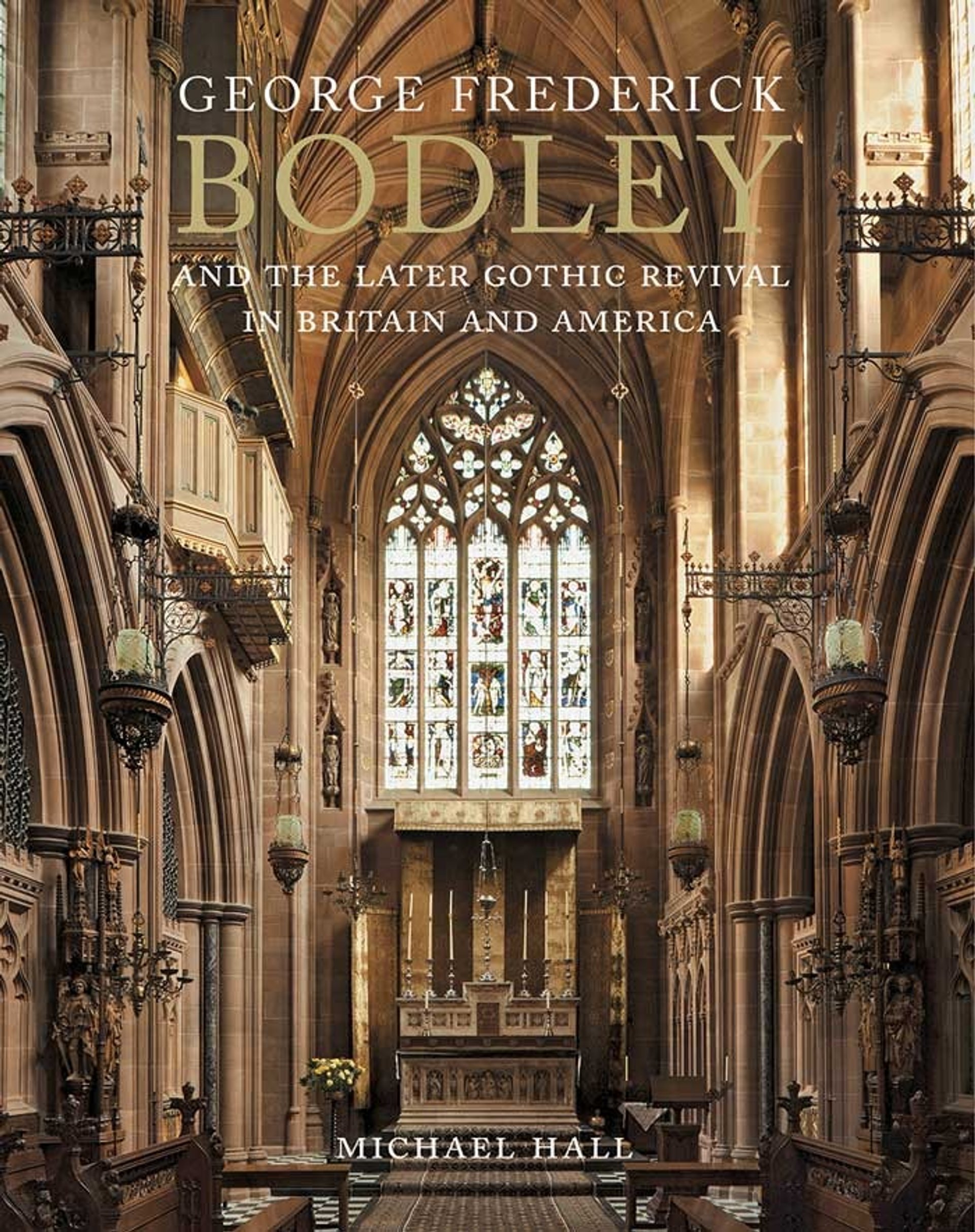

Michael Hall’s massive, exhaustively researched and hugely enjoyable George Frederick Bodley and the Later Gothic Revival in Britain and America is much more than a study of Bodley’s architecture: it sets the man and his work in the broad context of later 19th-century religious, artistic and intellectual history. Perhaps most significant is Hall’s advocacy of Bodley as a key figure in the Aesthetic Movement—which makes some sense of the charges of “preciousness”. It was Bodley’s passionate Paterian and Wildean commitment to beauty that drove him to exclude the discordant and the expressive. His buildings were conceived as vessels for an equally exquisite High Anglican liturgy. Bodley’s devotion to the Church of England was as fundamental to his work as was that of Roman Catholicism to that of Pugin. Incense is a necessary accompaniment to Bodley’s church architecture.

The great shift in Bodley’s stylistic palette, reflected in his designs for All Saints, Cambridge (1860-61), saw him reject Continental Gothic models for the medieval English Gothic that had inspired Pugin. Hall’s emphasis on the extent of the latter’s influence on Bodley is timely and convincing. “A great artist and a most beautiful character”, as Comper described him, Bodley, the architect and the man, is well served by this groundbreaking monograph.

George Frederick Bodley and the Later Gothic Revival in Britain and America

Michael Hall

Yale University Press, 508pp, £50, £85 (hb)

Kenneth Powell is an architectural historian, critic and consultant based in London. He has written extensively on 20th-century architecture but remains a passionate Victorian at heart. Victorian churches are a special concern in his work as a member of the London Diocesan Advisory Committee. He is an Honorary Fellow of the RIBA.