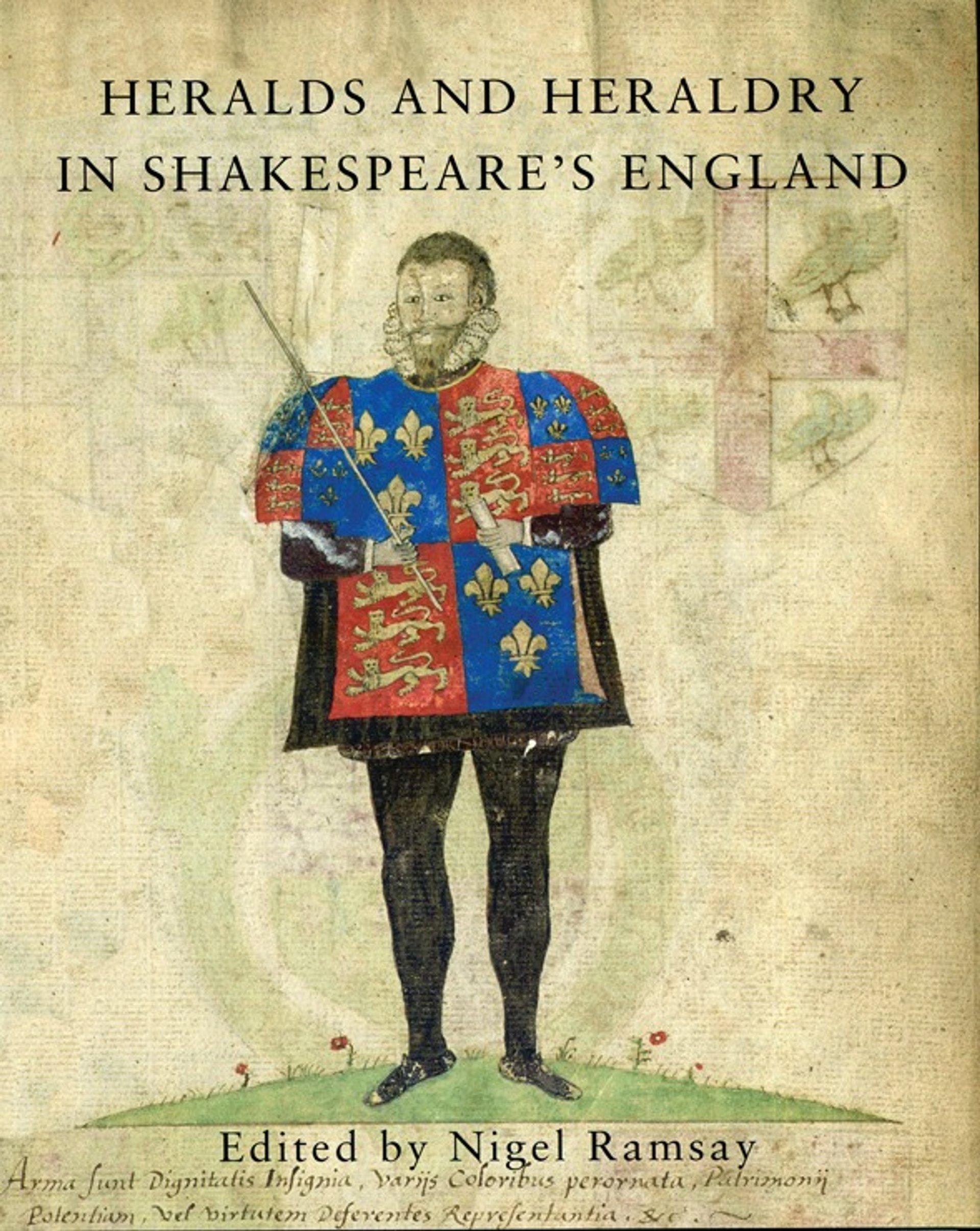

The four great libraries of English heraldry are, in order of importance, the College of Arms and the British Library, London, the Bodleian Library, Oxford, and the Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington, DC. Heralds and Heraldry in Shakespeare’s England has emerged from editor Nigel Ramsay’s research fellowship at the Folger in 2009 and the subsequent exhibition there of its rich collection of heraldic manuscripts in 2014. This led Ramsay to embark on a systematic, scholarly treatment of the English heraldic world in the Elizabethan and Jacobean period.

Those years were one of the Golden Ages of English heraldry and this Elizabethan flowering was part of the general cultural revival of Medieval chivalry during this period. It is reflected in poetry, court masques, jousts and theatre as well as fanciful symbolic or emblematic architecture, especially the construction of fantasy “castles” and lodges such as Lulworth, Bolsover, Cranborne and Lyveden New Bield. This accompanied the development of serious antiquarian scholarship, in which the heralds of the College of Arms played a major role, leading to the founding of the Elizabethan Society of Antiquaries.

The book is composed of 12 principal essays, the first two by the editor and the others by leading scholars of the subject including two officers of arms, the emeritus keeper of heraldic manuscripts at the British Library, the emeritus Downing professor of the laws of England at Cambridge, the former curator of 16th- and 17th-century British art at Tate Galleries, the keeper of Early Modern records at what used to be called the Public Record Office and various professors and lecturers at a range of universities. Their combined scholarly expertise is awesome. (Whenever one reads such authorial lists one always feels it would be better to be governed by such brains rather than a bunch of philistine PPE nerds!)

Knowledge of heraldry, like Latin and Greek, was until recently a sine qua non of a civilised man in England. But probably at no time was the subject as popular as in the 16th and 17th centuries when, as an art and a science, it was an integral part of the English Renaissance culture. Heraldry enjoyed unprecedented popularity as a mark of honour and of social status in England at a time when it was becoming moribund in the rest of Europe. This is thanks to the late Plantagenet and Tudor monarchs who regulated and encouraged it as a mark of status and means of integrating social mobility into the established ranks, by encouraging new grants of arms as well as recording old arms and genealogies.

The College of Arms had been founded by King Richard III in 1484, and the power to grant new arms was delegated to the Kings of Arms at the College, under the immediate direction of the Earl Marshal. It was established in its present premises at Derby House in the City under Queen Mary and King Philip. The 16th-century heralds were remarkable men, and they alone had the knowledge and authority to draw up arms. By conducting heraldic funerals and conducting visitations (established by the Tudors to police the use of arms) and by researching and drawing up families’ pedigrees as well as granting coats of arms, crests and badges (for all of which they charged fees), they earned substantial incomes.

The chapters explore different aspects including Grants and Confirmations of Arms by Clive Cheesman, Richmond Herald; and Tudor Pedigree Rolls and Their Uses by Sir John Baker.

As the book emerged from the Folger Library, there is an emphasis on Shakespeare and the use of heraldic language and identity in Shakespeare’s plays, and the role of literary and dramatic heraldry. “A herald, Kate? O put me in thy books!” is a reference to heraldic visitations, when officers of arms had the power to destroy unauthorised heraldic decoration. The Shakespeares themselves were typical of new grants of arms to upwardly mobile families. The playwright’s father, who received the grant, was a prosperous glover of Stratford.

This intelligently written and appropriately illustrated book is full of fascinating information and shows how historic heraldry is an essential tool in the interpretation of architecture, painting, especially portraits, and even the literature of the period it covers. Above all, Karen Hearn’s essay, Heraldry in Tudor and Jacobean Portraits, is essential reading for those interested in the visual arts.

Heralds and Heraldry in Shakespeare’s England

Nigel Ramsay, ed

Shaun Tyas/Paul Watkins Publishing, 344pp, £40 (hb)

John Martin Robinson is an architectural historian, Maltravers Herald of Arms, and the vice-chairman of the Georgian Group. He is also the archivist for the Dukes of Norfolk. His most recent book is James Wyatt, Architect to George III (Yale University Press).