Los Angeles

A new database set up by the Getty Research Institute will make it much simpler to research Nazi-era provenance, and could set off a flurry of restitution cases. The site provides access to most German auction catalogues from 1930 to 1945, and will “help immeasurably in the work of establishing provenance”, says Anne Webber, the head of the London-based Commission for Looted Art in Europe.

This could lead to a rise in the number of restitution claims because the site should “enable museums, collectors and the trade to identify more works that may be subject to claim”, says Lucian Simmons, the director at Sotheby’s responsible for restitution issues. Evelien Campfens, the director of the Dutch Restitutions Committee, expects the database “to lead to more claims on works that found their way from Germany into Dutch museum collections”.

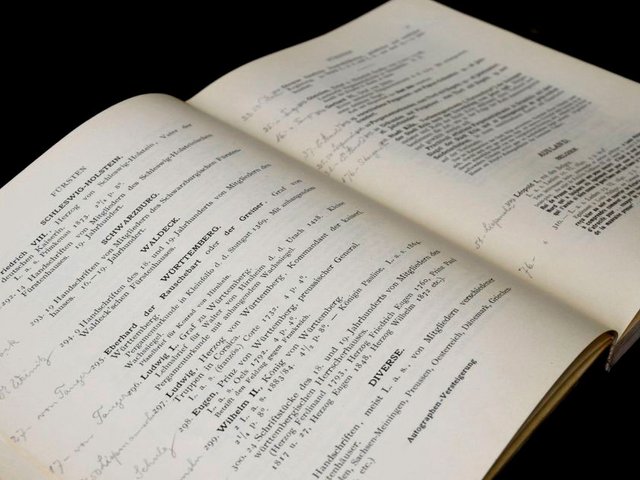

The Getty database covers 2,000 auctions and records 230,000 works of art. The site is simple to search, making it quick to track down details of pictures. After an entry has been found, one click brings up the scanned auction catalogue. The database records numerous paintings by Rembrandt (263) and Renoir (45), for example, and further details, such as title or subject matter, can be used in a search to narrow down the field.

The New York lawyer Lawrence Kaye, who specialises in restitution cases, welcomes the new database. “[Previously] one had to look through countless catalogues in libraries across the globe. Now, the task should be greatly simplified, and in some cases take no more than a few minutes.” But he stresses that, although the database may suggest an item was the subject of a forced sale, it cannot “prove the contrary—that it was not”.

The database grew out of an earlier venture by Heidelberg University Library to scan German, Austrian and Swiss sales catalogues from 35 libraries (including those in Berlin museums). These have been available online for the past two years, but are not as easy to search as Getty’s database.

As well as helping with restitution cases, the database will be a valuable resource for art historians and for those wanting to study the German art market in the mid-20th century.

BOX

Dissecting Getty’s anatomy of a forced sale

To show how the new database works, the Getty points to a limewood sculpture of St John the Baptist, around 1515. It was acquired by the J. Paul Getty Museum in late 2011, after it had been restituted to the descendants of the original owner by Stuttgart’s Landesmuseum in Württemberg. The heirs then sold the work at Sotheby’s, where it went to the Getty for £313,250. Had such a sculpture appeared on the market without its provenance information, it is questionable whether the pre-war owner would have been identified, partly because it is unsigned and partly because, in the 1930s, it had no artist’s name attached (it is now attributed to the Master of the Harburger Altar).

Searching the new database for “Johannes”, “sculpture” and “German” yields nearly 400 results, but narrowing down the field to “16th-century anonymous” brings up 120 results, all of which have descriptions. One of these entries, with an image, shows that this sculpture of St John the Baptist was sold by Jacob Oppenheimer at Berlin’s Achenbach auction house in 1937, in what is now seen as a forced sale. As Christian Huemer of the Getty Research Institute explains: “If you didn’t know about the 1937 sale, this information would have been virtually impossible to find.” M.B.

• For more on the Getty’s provenance research, visit www.getty.edu/research/tools/provenance