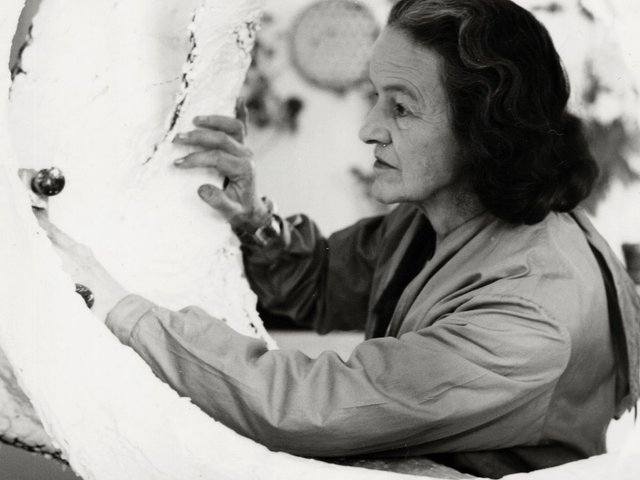

Barbara Hepworth: the Plasters celebrates the opening of a new museum named after the artist (1903-75) —the Hepworth in Wakefield—and a gift of her work to inaugurate it. The first three chapters deal with the history of Hepworth’s relationship with Wakefield (by Frances Guy), the building project that resulted in the new museum (by Gordon Watson), and the problems of designing the building, by its architect (David Chipperfield). The Hepworth gift of plasters and other prototypes, comprising 44 items, of which five are in aluminium and three in wood, was promised by the artist’s estate provided that “a building of architectural distinction and museum standard” was made available to house them. The new building by the River Calder is the impressive result.

The plasters which dominate the gift were the prototypes for bronzes and thus only a stage in the realisation of the finished sculpture, not the work itself. Thus a number of them were destroyed, either by the foundries or by the artist herself. Why were some kept and not others? There doesn’t seem to be any particular reason, but they are absorbing and memorable objects. Particularly striking (from among the beautiful full-page reproductions in this book) are Pierced Form (Amulet), Bird Form, Rock Form (Porthcurno), Spring, all from the 1960s, and the majestic maquette, Conversation with the Magic Stones, 1973-74.

Chapter four consists of a lengthy discussion by Sophie Bowness of Hepworth’s studio practice, culminating in an examination of four commissions: Meridian for High Holborn in London (1958-60), Winged Figure for John Lewis in Oxford Street (1961-63), Single Form for the United Nations in New York (1961-64), and Theme and Variations for Cheltenham (1969-72). Nearly half the book is taken up with a catalogue of the Hepworth gift, also compiled by Bowness, with conservation notes on each piece, where appropriate. There is a subsequent chapter on conservation, by the specialist Jackie Heuman, and finally a glossary of technical terms and a useful chronology. The tone is highly technical throughout—this is a book for people who already have a good working knowledge of Hepworth. It is not an introduction to the artist, nor does it examine in any depth the well-springs and abiding themes of her creativity. There remains a pressing need for a good, general introduction to this important (and still comparatively neglected) artist.

John Skeaping (1901-80) was Hepworth’s first husband, and a very considerable sculptor whose influence upon her early work was of critical importance. Enormously talented (Henry Moore said that no one of his generation had “greater natural facility”), Skeaping was from the start more interested in making good sculpture than in adopting a self-consciously “modernist” attitude. The radical simplification and power of his early work made him briefly popular with the arbiters of taste in 1920s and 1930s England, and his career flourished. But he was resolutely anti-intellectual in approach and amazingly indifferent to the fate of his finished works, joking: “I don’t have a posterity complex.”

An Essex boy who first studied painting before beginning to sculpt, Skeaping trained at Goldsmiths, the Central School and finally the Royal Academy, winning the RA Gold Medal in 1921 and the Prix de Rome in 1924. He married Hepworth in 1925, they separated in 1932 and divorced in 1933. In the late 1920s their work was so close as to be “virtually indistinguishable”, according to Jonathan Blackwood, but, by the early 1930s, they had moved far apart. Skeaping had rejected all notions of the avant-garde (his particular antipathy to Herbert Read didn’t help) and after 1934 he didn’t have an exhibition for 17 years. He spent much of that time travelling abroad, racing horses and greyhounds and letting his career go hang.

Fortunately, he didn’t stop work entirely, and in later life he became a celebrated equestrian sculptor. However the sporting fraternity who commissioned Skeaping’s late work were worlds apart from the art establishment, and his reputation got lost somewhere between the two camps. There hasn’t been a publication on Skeaping since the catalogue of his posthumous show at Ackermann Gallery in 1991, and although his work regularly appears in group surveys, it is generally assumed that there’s not enough to make a good museum exhibition. This book proves that wrong. Although there is a truly horrifying list of lost works in the catalogue raisonné (more than 100 out of a total of 253), there are still plenty for a major Skeaping reassessment; just the sort of show that the new Hepworth in Wakefield could aptly mount to great effect. Although this book is not a particularly well-rounded or satisfactory introduction to Skeaping’s art, it has done a great service by bringing to our attention the forgotten breadth of his achievement. Worth buying for the illustrations alone.

Barbara Hepworth: the Plasters, Sophie Bowness, ed. Lund Humphries, 200 pp, £35 (hb)

The Sculpture of John Skeaping, Jonathan Blackwood, Lund Humphries, 152 pp, £45 (hb)

Originally appeared in The Art Newspaper as 'An institution and her ex'