Jeremy Deller’s Baghdad, 5 March 2007 was unveiled in the atrium of the Imperial War Museum (IWM) in London last month. The temporary installation of a car mangled by an explosion in the Iraq capital makes a dramatic contrast to the military hardware nearby.

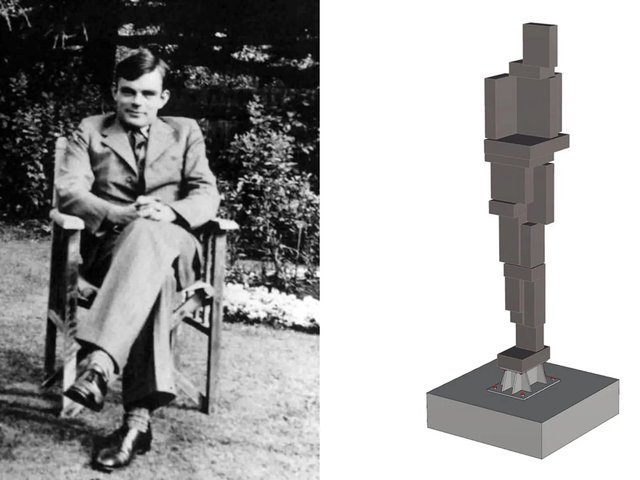

It is not the first time a thought-provoking sculpture has been mooted for this space in the museum, however. In 1986 Antony Gormley proposed an equally dramatic sculpture for the space.

“It was a simple idea,” Gormley recalls. “A lead body case of a female child. It would have been tiny, about 60cm high.” The placement of the sculpture was critical. Gormley intended it to be placed between the V2 rocket and the Polaris missile on display. “Those two phallic objects that represent the second and cold wars,” he says.

Angela Weight, then the curator of art at the IWM, worked with Gormley on the commission. “The idea hit you in the solar plexus—it forced you to think what war was about in this highly gendered space.” She was dismayed when it was referred to the board of trustees. “I knew they were not going to like it. They were in their sixties and conservative with a small ‘c’. I can imagine they found it an extremely threatening proposal,” because of its underlying “sexual provocativeness”.

Alan Borg, the director general of the IWM at the time, oversaw the institution’s transformation from a military memorial to one that also tells the social and cultural history of Britain and the Commonwealth at war. Borg remembers Gormley’s proposal well. “I was enthusiastic. It would have been very striking,” he says. “But it was a step too far for the board.”

The chairman of the museum trustees was the late Sir John Grandy, who fought and commanded a squadron during the Battle of Britain before becoming marshall of the RAF. Grandy killed the commission dead, remembers Gormley.

“We cannot have an image of weakness in the museum,” Grandy said, the artist remembers. Borg says the trustees were senior military figures, a lot of whom had fought in the second world war: “They thought it would be disrespectful,” he says. “Had the commission gone ahead the museum might have had the first public Gormley. Alas, it never happened.” Upset at the time, Gormley is philosophical about the incident now. “It was a good starting point. It got me used to being challenged,” he says.

The museum has a fragment of the commission: a sketchbook of the artist’s ideas showing how they developed. As well as the final concept, it includes ideas for larger body casts in various poses, mainly life-sized, although there is one monumental figure as tall as the flanking missile and rocket.

How does Gormley feel seeing Deller’s work where one of his might have stood? “I think Jeremy’s piece is terrific,” he says of Baghdad, 5 March, 2007, which Deller toured across the US last year (The Art Newspaper, June 2009, p37), supported by Creative Time.

Deller had wanted to place the car wreck on Trafalgar Square’s Fourth Plinth, which was, in fact, occupied by Gormley’s One and Other, during which hundreds of volunteers spent an hour on very public display.