Roman emperors are exceedingly good value. After two millennia, they are still with us, still capable of surprising and entertaining, of impressing and appalling, of defining their own era while still seeming topical, familiar and ultra modern. Augustus, cool control-freak and slick propagandist, had a heyday in the 1980s (exhibitions at the British Museum and in Berlin as well as the publication of Paul Zanker’s immensely influential The Power of Images in the Age of Augustus), but he had previously been portrayed as a bluff soldier (by Brian Blessed in “I Claudius”, BBC, 1976) and has since featured as the child and youth Octavian (Etonians Max Pirkis and Simon Woods) in the ridiculous but hugely popular TV epic “Rome” (HBO/BBC 2005, 2007). The anniversary of Constantine the Great, the first “Christian” emperor, more modestly hit the headlines in 2005 to 2007 with exhibitions in Rimini, York and Trier.

Midway between those two lies Hadrian (reg. AD117-138), whose architectural exploits were the subjects of exhibitions in Rome, Paris and his villa at Tivoli in 1998-2000 and is now celebrated in a very different show devised by Thorsten Opper at the British Museum (24 July-26 October; see p61), of which this is the book.

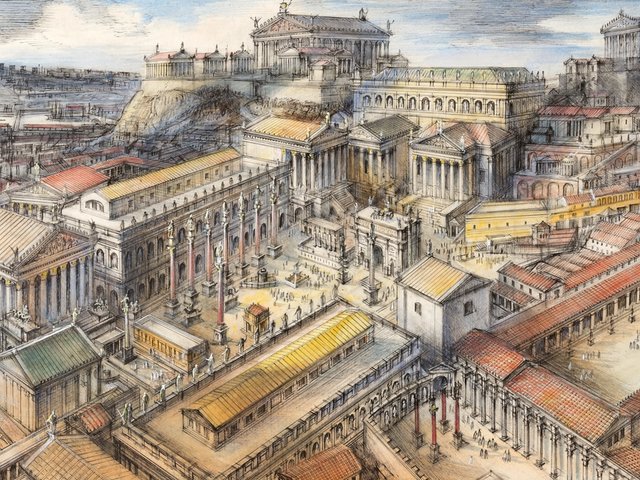

Hadrian: Empire and Conflict is an ambitious and refreshingly hard-headed take on the modern myth created by Marguerite Yourcenar’s Mémoires d’Hadrien (1951). He is not her philhellene pacifist, nor a practising architect, nor quite the hero more recently claimed by the gay community; he is a politically savvy, calculating, hard-working, vicious, tough, lion-hunting, married homosexual army general in the best Roman tradition. Born into the circle of fabulously wealthy Spanish olive-oil magnates who rose to power in Rome under their compatriot, the emperor Trajan, he was one of Trajan’s protégés and was eventually adopted by him as son and successor at the last minute as the latter lay dying in Cilicia, returning to Rome after a disastrous campaign against Parthia (modern Iraq). With the empire in turmoil and revolts stirring everywhere, Hadrian had no option but to reverse Trajan’s expansionism; he dissolved the new province of Mesopotamia and renounced other recently acquired but untenable possessions; he travelled from one end of the empire to the other, quelling internal unrest, stabilising vulnerable frontiers, setting the army to building Hadrian’s Wall in Britain and another in Algeria. His legions suppressed the Jewish uprising under Simon bar Kokhba with horrific violence, ending in the abolition of Judaea itself and the creation of Syria-Palestina. He wooed the eastern Greek aristocracies (Athenians in particular) into loyal and enthusiastic allies, giving them a new sense of their own identity through a Panhellenic league but also encouraged them to enter the senate at Rome, finally completing the great Temple of Zeus in Athens (after 700 years), building a great temple in Rome in the Classical Greek style (but for local deities Venus and Roma), drawing the Roman senatorial class into the process by his own appropriation of élite Greek culture.

We are introduced to Hadrian’s family, his jealous cousin, his wet nurse Germana, the distinctive crease in his ear lobes (diagnostic of coronary artery disease these days and also a way of telling his real portraits from fakes), the amphorae in which the olive oil from his grandfather’s Spanish estates would have travelled to Rome and the bricks made on his female relatives’ estates in the Tiber Valley. We are told something of the design, construction and decoration of the Pantheon and other projects in Rome, followed by an effusive tour of Hadrian’s villa near Tivoli, its layout and constituent parts, its staffing and functions, the mosaics, paintings, coloured marbles and statuary which accompanied the endless bathing and dinner-parties. Then there’s his lifelong passion for hunting, and for sex with boys, and his shorter-lived love for one of his huntsmen, the beautiful Bithynian youth Antinous who later drowned in the Nile on a tour of Egypt. Hadrian instantly declared him a god and his cult spread rapidly around the Mediterranean, especially among the aristocracy. A grand Antineion was built beside the entrance to the villa at Tivoli, recently excavated, and probable source of the Pincian obelisk and many Egyptian and egyptianising sculptures recovered in the past. On his own death, Hadrian was buried with his wife Sabina, who died the year before, in the huge dynastic mausoleum which he had constructed on the banks of the Tiber at Rome (now Castel San Angelo). Deification by the Senate and a temple in Rome, by now de rigueur for the smooth transfer of imperial power, were enforced by his chosen successor (the comparatively boring Antoninus Pius). Immortality, Roman style, was assured.

Richly illustrated in colour throughout are almost all the 164 objects in the British Museum exhibition (not catalogued as such but given as a checklist at the end), as well as specially drawn maps, plans and diagrams. There is something new for everyone: the latest find of a colossal marble Hadrian from Sagalassos in Turkey; bits from the newly discovered Antineion at Tivoli; bronze peacocks from the perimeter wall of the Mausoleum in Rome and some massive chunks of its marble ornament; the museum’s famous statue of Hadrian in Greek dress from Cyrene, which has turned out to be a 19th-century pastiche; the Young Hadrian from the Prado; the bronze Hadrian from Beth Shean; finds from the Cave of Letters and other relics of the Bar Kokhba revolt; luxury mess tins, distance markers, tools and other equipment from Hadrian’s Wall; a silver dish with an image of Antinous from a tomb at Armaziskhevi (Republic of Georgia). Footnotes, bibliography, glossary and index round off an already attractive and enjoyable monograph in exemplary fashion.

Originally appeared at The Art Newspaper as 'Immortality, Roman style'