Over 80 years have passed since Amedeo Modigliani died at the age of 36 in 1920, yet, with exhibitions such as the recent “Modigliani and his models” at London’s Royal Academy and the publication of Jeffrey Meyers’s biography, Modigliani a Life, interest in this artist does not seem to diminish. Often secondary in discussion to his notoriously hedonistic lifestyle, Modigliani’s art, with its instantly recognisable traits—the reclining nudes, the elongated features of his faces, their blank or blackened almond-shaped eyes, the heavy linear outlines of his figures—has provoked debate between his champions and critics.

One camp, starting with Gertrude Stein, holds him as one of the most important figurative painters of our time, and the other brands his work repetitive and unimaginative. Mr Meyers’ book sadly fails to discuss these contentious opinions or the reasons behind them. However, the author does succeed in presenting his reader with a compelling and sensitive rendering of Modigliani’s life, addressing the seedy underbelly of the bohemian lifestyle which characterised the Parisian art scene at this time, without resorting to the “tabloid” tone of previous biographies on the artist.

Born in Livorno, Italy, in 1884 to a wealthy Jewish family, “Dedo” as he was known to his relations, is described by Mr Meyers as a classic “mummy’s boy”. The dependence on his dominating mother was heightened due to recurring periods of sickness that plagued the artist’s early life. A bout of typhoid fever in 1899 resulted in a long period of convalescence, during which he learned to paint—studying the old masters—and read widely. A year later he contracted tuberculosis and, in an attempt to stimulate his recovery, he was taken by his mother to recuperate in Naples, Capri, Florence and Venice. It was during this time that Modigliani’s passion for art blossomed, and in 1902 he enrolled at the Scuola Libera di Nudo in Florence where he studied life drawing under Giovanni Fattori. Alongside this technical education, Modigliani discovered the bohemian lifestyle adopted by contemporary artists in Venice and Capri. Under the influence of Lautréamont’s hallucinatory, satanic monologue, Les Chants de Maldoror, he began experimenting with alcohol and hashish, and enlarged his sexual capital by exploiting his notoriously good looks. According to Mr Meyers, it was at this point that the artist “ceased to be the conventional young man” of previous years and began to neglect the classroom, sketching and drawing mainly in cafés and brothels.

Mr Meyers accords with the received opinion that this discovery of the sins of the flesh turned his thoughts to Paris, where he went in 1906, leaving “Dedo” behind to reinvent himself in Montmartre as “Modi”, homophonically alluding to his new status as a decadent “maudit”. Here he was welcomed into the youthful and bohemian art scene, and befriended by Max Jacob and Pablo Picasso among others. Mr Meyers rather bluntly states that, “Picasso shattered form, Modi preserved it”. Although this is an intriguing comment and worthy of discussion, it is typical of his tendency to make perceptive yet sweeping statements that he fails to expand upon. The large part of the book is dedicated to the telling of the well known yet compelling tale of a young artist’s descent into squalor. During his lifetime Modigliani sold very few works, often exchanging drawings for food, art supplies and, above all, alcohol and drugs, which hastened his death from tuberculosis. The two main patrons of his work, Paul Alexandre and Léopold Zborowska, fuelled the artist’s addictions, the latter often locking Modigliani in a studio with nothing but his materials, a model and a bottle of spirits. Modigliani famously declared that he could only work with live models, the majority of whom were also his sexual partners.

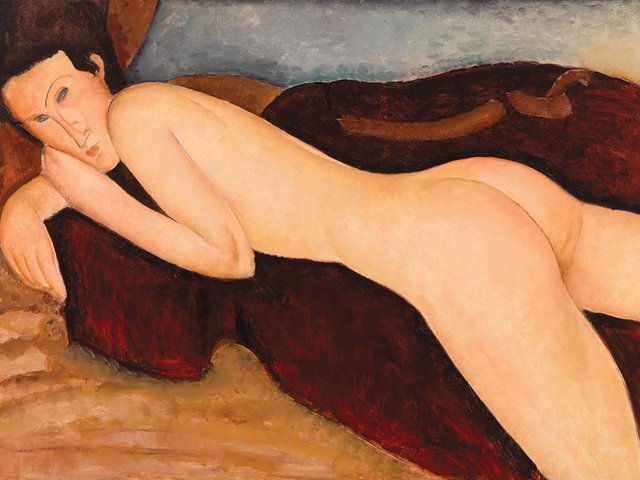

It is the relationship between Modigliani and his sitters that forms the subject of Modigliani and his Models, the catalogue of the recent RA exhibition. The catalogue presents Modigliani as the saviour of the classical nude: bridging a seemingly impossible gap between the Italian old masters and his contemporaries in Paris who were eager to reject the traditional, academic style. The reclining nudes epitomise this enterprise. The application of flesh tones in these images, built up in layers to emulate the warmth and depth of a live model, recalls the traditional approach to painting female nudes. Modigliani combined this tradition with the fashionable primitive vocabulary: thick, black contours and simplified, angular features with hollow eyes reminiscent of African masks. Modigliani revelled in the tradition of rebellion: his female nudes were also his attempt to align his art with Manet and the other 19th-century rebels in their use of naked women to épater la bourgeoisie. Deemed “sexually explicit”, his nudes were exhibited in 1917 at Berthe Well’s gallery. The ensuing public outrage was so fierce that the offending pictures were removed after a few days, cutting short the artist’s only solo exhibition in his lifetime. These days any mention of nudity, male or female, in the academic world, prompts a discussion into the objectification of the model under the (invariably male) viewer’s “gaze”. Although a well-worn path, the subject can be interesting, and considering the exhibition’s title, it would be remarkable were it omitted. Emily Braun’s essay “Carnal Knowledge” is presumably meant to address this subject, but fails to reach any satisfactory conclusion. Indeed, Ms Braun’s opinion that Modigliani’s approach to his models was based on “respectful adoration” is flatly contradicted by Mr Meyers. His picture of the women in the artist’s life—Beatrice Hastings, Simone Thiroux and Jeanne Hébuterne—is pretty bleak. Two of these three committed suicide, Hébuterne killing herself and Modigliani’s unborn child by throwing herself from a window two days after the artist’s death.

Although both of these publications are engaging and accessible, neither offers new information about the author. Modigliani fans will not enrich their knowledge and critics will fail to be swayed. Crucially, both fail to address the conflicting reactions to his work and the reasons behind these opinions, focusing instead on a short life made spectacular by self-indulgence.

Originally appeared in The Art Newspaper as 'Love him or hate him? Whatever…'