Tom Atwood confesses, in his “artist’s note,” that “[t]he subjects in Kings in their Castles are admittedly by no means a representative social or ethnic cross-section of gay New York.” No kidding. Atwood works with a sincere sense of a “gay male community,” something not all “gay males” are likely to understand in the same way, but what these 71 colour photographs really document is a handful of New York’s creative and executive élite. Or what Charles Kaiser in his foreword calls, at once admiringly and euphemistically, “gay men of ambition”. But as one of Shakespeare’s gayer Kings, in a castle not his own, observed, “Thoughts tending to ambition, they do plot /Unlikely wonders.” And Kings in their Castles is a frequently wonderful book.

Are these portraits or interiors? Atwood writes that he attempts to balance subject and environment, such that neither predominates. When this balance is struck, the effect is enchanting. Edmund White sits square to the camera, meeting the viewer’s gaze, interested and amused. The curve of his left arm, holding an apple in his lap lower right, echoes the arching Anglepoise lamp, upper left, such that the composition turns around the chair-back where his right arm, upper body, and head gently incline. His pose is casual and ordinary: the gracefulness is derived in relation to this particular environment.

Compare the doll-maker Timothy Bellavia, wearing an expression of serene concentration, his eyes downcast, almost closed, like a Tibetan Buddha. It is the wide-eyed pop-art pictures of female faces behind him that meet the camera head on. (Mr Bellavia is busy right now—his apartment will see you instead.) At best, this balance is also a dialogue, with particular living spaces suggesting styles of portraiture. Atwood finds agreement in this dialogue, in part because his frame of visual reference is unostentatiously educated.

For instance, he photographs the dance essayist David Lerner amid his shadowy, baroque décor with something of the dynamic chiaroscuro of the 17th century: in the better of the portraits, he sits reading the instruction manual to a new VCR, front-lit against the darkness, his brow furrowed like a Caravaggio saint struggling with the word of God.

Or the quirky portrait of the fashion designer Douglas Ferguson, pictured in his bath, his arm draped over the side like Marat: in the foreground, disproportionately massive, his white cat stands on the front rim of the tub, staring at him both menacing and funny, a fat furry Charlotte Corday.

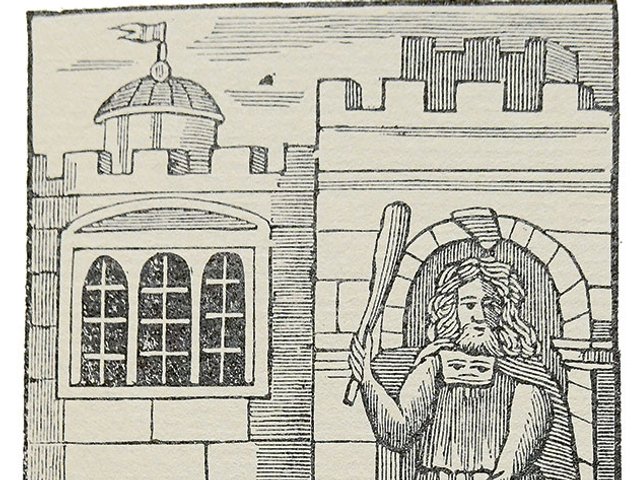

“Gay people take great pride in cities,” Atwood writes. And New York, more than most cities, has returned the compliment. Even so, there is another truth: that pride, like its corollary, shame, is a reaction of people under scrutiny. As Atwood acknowledges, these kings’ castles are partly defensive, battlements against the pressure of “a society that would like to convince us of our inadequacies”. Hence the tension between private and public, between homes as sanctuaries and as statements, reflected in Atwood’s compositions as a quiet tussle between composure and pose. As one of New York’s sharper gay residents (not featured) put it, “all these poses, such beautiful poses,” and many of these kings are holding court. Atwood thinks the gay man’s home “a metaphysical extension of himself,” but one might just as well prefer “of his self-consciousness”. And it is this complex sense of private showmanship, rather than any innate gay aestheticism, that sets these photographs apart from straight portraiture or merely aspirational interiors. How unlike, how very unlike, the home life of our own dear Queen.

o Tom Atwood, Kings in their Castles: Photographs of Queer Men at Home (The University of Wisconsin Press, 2006), 80 pp, $35 (hb) ISBN 0299211509