In a ruling that defied nearly all expectations, the US Supreme Court held on 7 June that Austria can be sued in American courts over its alleged wrongful retention of six paintings by Gustav Klimt that were looted from their Jewish owner by Nazis. The decision is a severe defeat for Austria and the Austrian National Gallery (ANG), which have fought since 2000 to keep US courts from hearing the case of the Klimts, formerly the property of the Viennese Czech sugar magnate, Ferdinand Bloch-Bauer, whose vast art collection was stolen by Nazis after the annexation of Austria in 1938 (see also p. 37). The decision is a rare ruling against a foreign nation and required the further unusual step for the Supreme Court of affirming a decision of the lower California federal appeals court.

The decision is a major victory for Ferdinand’s niece and heir, Maria V. Altmann, who fled Nazi Austria aged 22 and is now a US citizen and California resident, and for her lawyer, E. Randol Schoenberg, of a three-lawyer firm in Los Angeles, who overcame Austria and the ANG, together represented by a major US law firm, Proskauer Rose LLP. The Supreme Court will now return the case to the California trial court, where Altmann will seek an expedited hearing based on her age of 88 years.

Few had believed that Austria could lose. But the complexity with which the court viewed Austria’s immunity claim was evident at oral arguments in February, where a number of justices seemed dissatisfied with the traditional analysis of foreign sovereign cases, and some, aided by Mr Schoenberg, seemed eager to fashion a new solution.

In an opinion written by Justice John Paul Stevens, a six to three majority said that in analysing whether the US Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act could apply to pre-1976 events, it found no “clear answer”

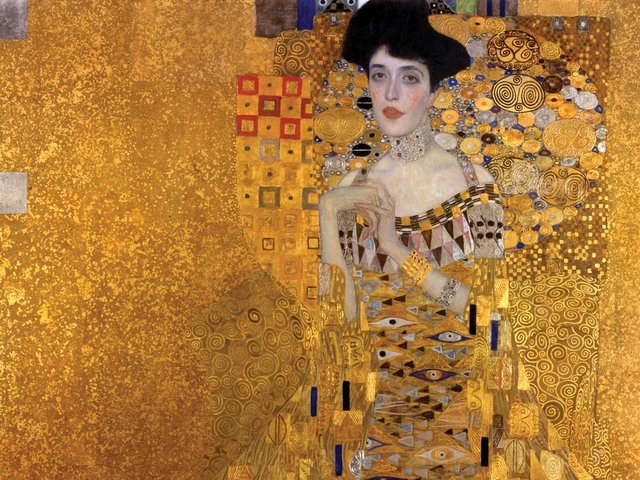

Ms Altmann’s allegations remain to be proven at trial. She says that after Nazis seized Ferdinand’s property, the six Klimts passed to a Nazi lawyer, Dr Führer. Dr Führer sold three of the Klimts directly to the ANG. These three, plus two others found after the war (one in Dr Führer’s hands and the second at the Museum of the City of Vienna which bought it from him), were then unlawfully and without authorisation extorted from the Bloch-Bauer family by Austria, in exchange for Austria’s grant of export permits which let the Bloch-Bauers remove other art from the country, Altmann says. (Art that was required to be donated in exchange for such export permits can now be reclaimed under a 1998 Austrian restitution law). The sixth Klimt painting, which passed from Dr Führer by an unknown route, was given to the ANG in 1988.

After the war, the ANG wrongly claimed that Ferdinand Bloch-Bauer’s wife, Adele, had bequeathed five of the paintings to it in her will, but neither Adele nor Ferdinand ever donated the Klimts, Ms Altmann says.

When Ms Altmann determined that court proceedings in Austria would be too expensive, she sued Austria in California in 2000. She cited a taking of property in violation of international law, one of the four circumstances in which the 1976 US Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act (FSIA) allows an otherwise immune foreign nation to be sued in US courts. But Austria claimed immunity anyway, saying that as a foreign sovereign it had been immune from suit when the events occurred in 1948, and that the 1976 FSIA could not retroactively change that. Two lower federal courts in California rejected Austria’s argument, and the Supreme Court agreed.

In an opinion written by Justice John Paul Stevens, a six to three majority said that in analysing whether the FSIA could apply to pre-1976 events, it found no “clear answer” using the retroactivity rule set out in a 1994 Supreme Court case, “Landgraf”.

“Landgraf” considered whether a new section of the Civil Rights Act, permitting parties to seek compensatory and punitive damages for intentional employment discrimination, applied to a lawsuit which was already pending when the statute was enacted.

“Landgraf” said that a statute cannot be applied to pre-enactment events if this would impair the rights or increase the liabilities relied on by a party to a lawsuit. An exception applies if Congress issues a clear statement of intent to this end at the time of the statute’s enactment.

But the FSIA “defies” a “Landgraf” analysis, Justice Stevens wrote. Foreign nations had no “right” to immunity from US lawsuit, and the purpose of sovereign immunity has been political comity, not protecting a foreign state’s “reliance” on expected immunity in US courts.

Unable to use its own precedent in “Landgraf”, the court said that “throughout history” courts had resolved sovereign immunity questions by deferring to “decisions” of the other political branches. In the unique context of the Altmann case, the court said it was appropriate to defer to the “most recent” political branch decision, which was Congress’s enactment of the FSIA, rather than decline to apply the FSIA merely because the statute postdated the 1948 events.

Moreover, the FSIA’s language and structure gave “clear evidence” that Congress intended it to apply to pre-enactment events. The court concluded that the FSIA’s exceptions allowing certain lawsuits against foreign nations “clearly applied to conduct, like [Austria’s] alleged wrongdoing”, that occurred in 1948.

The court emphasised the narrowness of its ruling, saying that foreign nations could still raise available defences to lawsuits, such as the “Act of State” doctrine, which bars US courts from judging a foreign nation’s public actions within its own territory. Finally, the court responded to the Bush Administration, which had sided with Austria saying that US foreign policy interests would be jeopardised if foreign states could be sued in US courts over pre-1976 events. The court said the State Department could still file a “statement of interest” in particular lawsuits to suggest that a court should decline to hear the case. Such a statement “might well be entitled to deference” the court said, adding, however, that it would not say whether “such deference should be granted.”

The Bush administration has indicated that it will not file a statement of interest in Ms Altmann’s case. Mr Schoenberg says that the Act of State doctrine does not apply in any case where a treaty applies, and that the Austrian State Treaty of 1955 requires Austria to return all property confiscated by the Nazis.

Those who disagreed

The rule against applying statutes retroactively is “a rule of fairness based on respect for expectations”, according to Justice Kennedy, Chief Justice Rehnquist and Justice Thomas, in their dissenting opinion. In 1948, Austria could have expected that the US executive branch could have requested immunity for it in such a suit. Altmann’s lawsuit should be sent back to the lower court to determine whether the court could have taken the case before the FSIA was enacted, including whether Austria’s alleged 1948 conduct constituted a then-exempt “public act”. The majority decision wrongly “opens foreign nations worldwide to vast and potential liability for expropriation claims” over events that occurred generations ago. Finally, the majority, by inviting the State Department to file a “statement of interest” asking courts to drop lawsuits in sensitive cases, has unnecessarily opened the door to the executive’s superseding the FSIA, a congressional statute which set out to standardise when a sovereign could be sued.

• Originally appeared in The Art Newspaper with the headline 'Supreme Court says Austria can be sued in the US'