If programme makers were asked to label their work as “beginners”, “intermediate”, “advanced”, or “mixed ability”, most would fall into the categories of “beginners” and “mixed ability”, with an occasional sally into “intermediate”, and an even rarer hint at the real complexities of a subject. It is in this last respect that the programmes often let us down.

Programme makers are bidden to demystify art gobbledegook. But by oversimplifying, the subject loses its richness and obscures real understanding. Intelligent producers know this. Do they have the courage to tackle the problem and, if so, how?

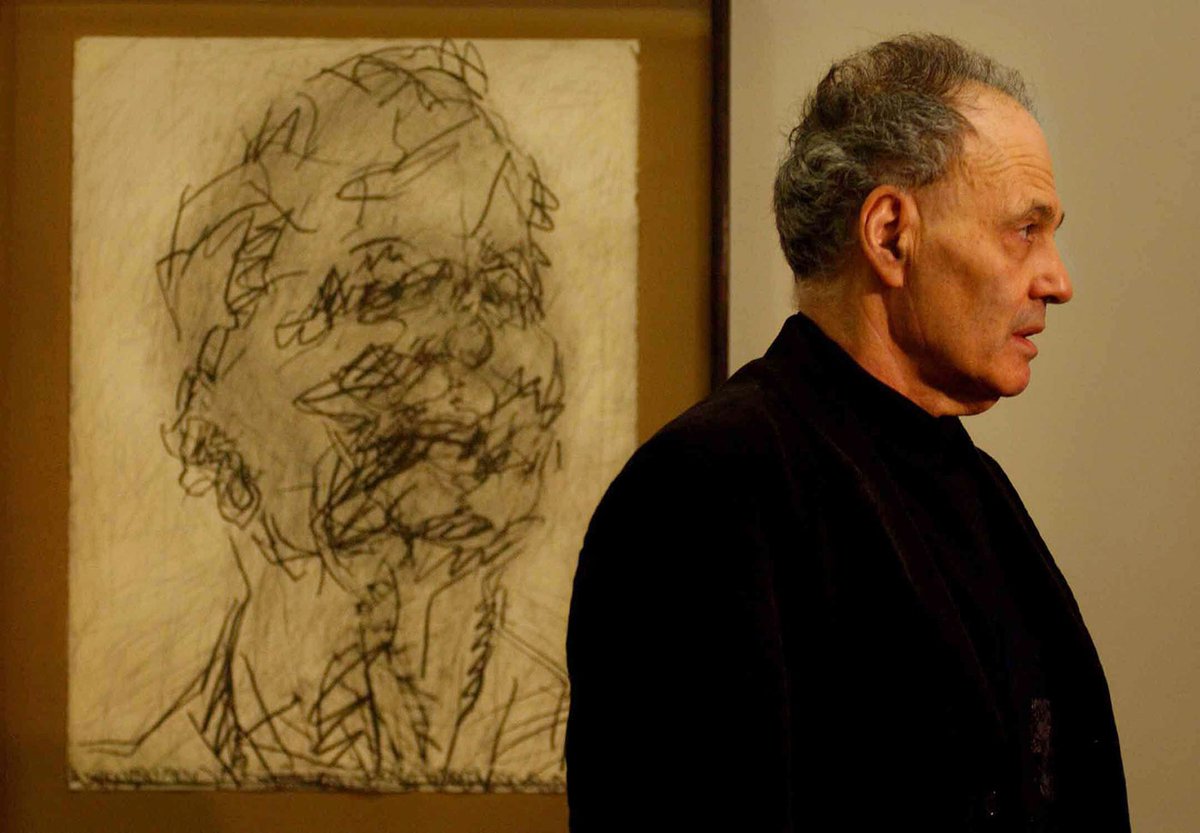

From the small shower of recent art features you could have watched, or listened to, programmes of two main types emerged: those about artists and their work, and those about ideas. We had two full-length programmes devoted to Frank Auerbach, currently exhibiting a wall of his drawings in the National Gallery, with a retrospective in the Royal Academy (until 12 December); one, an interview with John Tusa on Radio 3, and the other, a television documentary for Omnibus. Three programmes complemented Tate Modern’s exhibition Surrealism: desire unbound, a Night Waves Special, BBC2’s Surrealism: a private view, and a discussion of Surrealism and psychoanalysis in Melvyn Bragg’s BBC Radio 4 series on the history of ideas, In Our Time.

Omnibus’s film about Frank Auerbach falls into the category of programmes which hark back to the golden years of TV arts, in which the camera discreetly recorded the artist at work over several hours and then edited a programme in which we felt that we had got closer to what Martin Amis refers to as the “emanation”. Amis, sharing a discussion about the contribution of the South Bank Show to arts broadcasting, was very positive about the celebratory nature of the shows because, as he said, they’re trying to open up a recondite area and bring it to “the people”.

It was a shock, then, to switch into Omnibus. Although Frank Auerbach has given a number of written and radio interviews, this eagerly awaited film by his son, Jake Auerbach, and Hannah Rothschild was a rare and praiseworthy event.

Throughout a long sequence of opening shots in which we mostly saw Auerbach’s back, walking down streets in London’s Mornington Crescent, where he has occupied a studio for over 40 years, he read the following letter. It needs to be quoted in full.

“Dear Jake!! A very quick, scribbly and incoherent letter to you and Hannah. Some of the things you said about a possible film last night make me uneasy. Hannah wrote me a letter many years ago asking me to appear on a programme designed to demystify painting. I refused, of course. The thing is, painting is mysterious and I don’t want to demystify it. It’s no good presenting artists as approachable blokes who happen to paint, although some may have the coolness, or the grace, to lend themselves to this. In this case, you would be dealing with someone who is prepared to answer questions and to explain but who is not prepared to lend himself to ‘performing’ in a film—as though he wanted to contact the ‘general public’. If I have ever thought of contacting anybody it is the misfit in the back room who rejects the general public and television films.

“[What I think I am saying, Dear Jake, is that] I think that Hannah should know what sort of beast she is dealing with—a beast in a burrow, that does not wish to be invaded. Of course, I don’t mind, and wouldn’t object to anything other people say, but I think Hannah should interview me before making filming plans.

“P.S. I go to the cinema when I’m tired, perhaps once a month, the theatre twice a year and watch television in the middle of the night when I can’t sleep at Finsbury Park. I’m not prepared to talk about any of this, let alone perform it. It is entirely irrelevant to a film, which I would prefer to be centred on the work and to answer questions arising from it.”

The sentiments expressed explain Auerbach’s wary, animal-at-bay, manner throughout the interview, that provided the backbone to the narrative. An unseen female interlocutor, presumably Hannah, put questions kindly, almost sotto voce. Yet a more uncomfortable interviewee is hard to imagine. Although Auerbach gamely replied to all the questions, his reluctant, melancholy manner contrasted strikingly with the jolly, relaxed boy, student and young artist, of the rostrum photographs. An opening close-up of his hands, tensely clasped and turning, set the strained tone of the interview in which he rarely looked up, barely smiled, only once radiantly when this artist who works 364 days a year for pleasure, admitted to being obsessive: “I hope so. Yes. I think so. A bit. Yes.”

The film was structured round a sequence of fascinating encounters with seven witnesses. All were models who have sat for him regularly on a set day each week for between 10 and 42 years, and who described the experience of seeing the image form, be eradicated and reform, session after session.

The destructive element to the creative process came as a surprise to some of them. “It seemed more like a fit,” Jym Briggs Mills told us. “He was very violent and quite in a world of his own and it was quite frightening in the beginning.” Finally after weeks of increasing intensity the likeness would gell in a single hour of rapid activity, Catherine Lampert said, pointing out the blotches and squiggles of paint on one of her portraits. “Every single stroke is fresh on the last day.”

If only the camera had been allowed silently to record that hour. It would not demystify painting, as Auerbach fears. It would reveal what only a few have been privileged to observe. It would have given us, too, the passion and spontaneity that came across in The John Tusa Interview. This was not the Auerbach who appeared unhappily on camera. Animated, fluent, he responded eagerly to Tusa’s knowledgeably forthright interviewing, scarcely waiting for the question to be asked before answering. Words, ideas, views on art from Giotto to video, poured out, wise and generous, sweeping the listener along with him.

His description of Bomberg’s influence did much to explain the hazardous “experimental journey”, of which the excellent TV film could only show us the conclusion, but none the less tellingly for juxtaposing sitter and finished portrait. “He had a sort of idiom that allowed one to go for the essence from the beginning, to adumbrate a figure in 10 minutes and then to redo it and find different terms in which to restate it until until one got something, unlike a poster or a photograph, that seemed to contain the mind’s grasp of its understanding of its subject.” If television crept us only a little closer to Auerbach’s work, we can probably agree with Alan Yentob on The South Bank Show that it’s “better to have it than not to have it. And have it where people can get excited by it.”

BBC2’s Private View of Surrealism: desire unbound at Tate Modern tried to do just that, to get a non-specialist, yawning viewer excited. Recommended for a teenage audience. The opening image in which the camera pulled out from an eye to the presenter, Waldemar Januszczak, full-face, was, if clichéd to old-timers, neat and arresting. Shots with blood-red skies and phallic towers set the scene. Supercharged prose kept us on the boil. Breton, Pope of Surrealism, “learnt from Freud”, Januszczak tells us, “that within us all is a bubbling vat of illicit desires. Yes, the subconscious, that secret câche of dark stuff into which the artists of Surrealism began dipping enthusiastically.”

What followed was a well-made programme in which Francis Whately applied a straightforward format, a tour though the exhibition stopping off at five points with appointed commentators from different disciplines, including Susie Orbach, a psychoanalyst and the novelist Will Self. Januszczak and guest stood on either side of the work. Each had time to express a view, uninterrupted. Steady shots or slow panning gave us plenty of time to look at the actual work. Apart from some flippant asides which undermined its critical role, this was a serious programme, presented at a popular level by Janusczcak with zest and professional polish.

A broader Surrealist panorama

While BBC2’s tour of the exhibition was selectively weighted towards sex and titillation to keep us amused, a Night Waves Special, broadcast live before an invited audience in Tate Modern, aimed at a broader, texturally richer, Surrealist panorama. Montages of archive material added sound colour. Inevitably the programmes covered similar ground, following the exhibition in rejecting posters and popularisation in their search for a definition. The Night Waves presenter Richard Coles ably orchestrated a discussion in which experts spoke about the relationship of Surrealism to art and psychoanalysis—Professor Dawn Ades and Lisa Appignanesi, to literature—Professor Mary Ann Caws, translator of Surrealist love poetry, with examples beautifully read in English and French by Simon Russell Beale, to film—Professor Ian Christie, and, less discussed than art and literature, to music—the American conductor Richard Bernas, with piano pieces by Satie and Antheil performed by Nicholas Hodges.

In the final section of the programme the discussion opened up to look at the influence of Surrealism on contemporary practice with Cathy de Monchaux, at “post-colonial” theory and the recycling of Surrealist kitsch imagery. We might have expected a more excited exchange, but the format did not favour debate, although from an earlier interjection the audience were clearly fired up. A new topical series, Undercurrents, built on similar lines, is planned for the New Year. We hope for turbulence.

It may be that Surrealism is still such a complex subject to grapple with that explainers must keep their calm. Certainly the only person who appeared agitated and almost inarticulate with sceptical confusion on In Our Time, unravelling in this instance Surrealism and psychoanalysis, was its inquisitor, Melvyn Bragg. His well chosen panel, Professor Dawn Ades again, Malcolm Bowie, Marshal Foch Professor of French Literature, Oxford University, and the psychoanalyst Darion Leader, elucidated the subject with precision, bringing in checks and balances and avoiding simplification. They remained unphased by Bragg’s chivvying determination to speak for the plain man: “So, we’ve got that. Let’s move on …”, “Yea, but what I want to know is…that’s what I want to know.” Near half-time Bragg’s bewilderment reaches exasperation: “I want to hammer away at this a bit. I don’t think I’m getting there yet, to tell you the truth.”

Malcolm Bowie: “Can I ask you a question...?”

Bragg: [interrupting]: “No, I want to ask you. This manifest and latent idea, can you just be clear about what these are in Freud and which the Surrealists took and why they took what they took.”

Bowie: “I think the manifest is...”

Bragg [interrupting again]: “Obviously if you’re swimming, you’re swimming. You dream about you’re swimming, you’re swimming. That’s manifest. Latent is why you’re swimming, that’s the interpretation of swimming, turning the visual into verbal and solving it and therefore revealing the wish.”

It was a matter sometimes of following the questions as much as the answers, but Bragg’s persistence paid off. For anyone interested in extending their understanding of the way the Surrealists manipulated both conscious and unconscious experience this was a stimulating listen. Intermediate to advanced, with Bragg standing in for the struggling beginner.