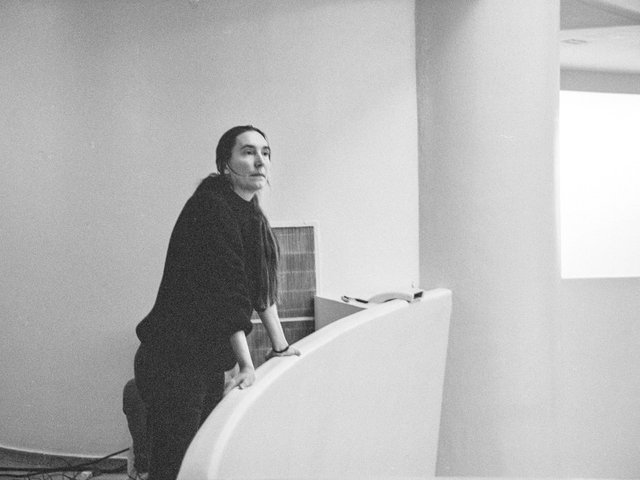

Jenny Holzer has the rare honour of being a contemporary artist as much beloved of the fashionable beau-monde as the intellectual and cultural elite which determine museum programmes throughout the world.

She is not to blame for any of this. Indeed, even if the world paid her no heed whatsoever she would still continue making her work with the very personal integrity and intelligence that has long distinguished her from any inherently careerist pack. Perhaps part of Holzer's secret is making art that is both challenging and oblique, which utilises entirely anonymous and open forms of communication yet somehow remains distinctly her own, recognisably a “Holzer” despite its democratic medium.

Holzer might be thought of as a “language artist” but one who takes the dry formulas of that cerebral generation of Conceptualists before her and mutates them into a direct form of political and social activism. Today she may help create the atmosphere for “Helmut Lang Parfums” in SoHo but it has to be said that it is by no means a normal atmosphere, let alone for a perfume shop. Likewise Holzer was selected by Karl Lagerfeld as one of the few named contemporary artists for his planned Chanel retrospective at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. This was rejected by the museum's director Philippe de Montebello for being a little too aggressively “now”.

Holzer is sincere, open, honest and by now very sophisticated when it comes to the games of both our wee art world and the larger arena of municipal and state politics.

William Burroughs once claimed “language is a virus from outer space”; if this is so then Holzer has spread her own trademark virus into the inner space of our consciousness as well as every day culture at large.

The Art Newspaper: What are your ideas for this new exhibition at Cheim & Read gallery?

Jenny Holzer: I want to show the most recent text oh, which has to do with a girl child, and I am making an installation that plays with Richard Gluckman’s galleries at Cheim & Read. I am hoping for a clear presentation of a rough subject.

Do you find the relatively intimate nature of a commercial gallery automatically leads to a very different approach to that of a public commission?

With museum exhibitions or a public commission in comparison with gallery shows, there can be more architecture or streetscape to work with or against, more subject matter readily available, and more people with whom to collaborate or wrestle. Regrettably, much of the intimacy of a gallery show is with myself. Working in public is in some ways easier than giving yourself the creeps as you make art solo.

Regrettably, much of the intimacy of a gallery show is with myself. Working in public is in some ways easier than giving yourself the creeps as you make art solo

That said, it often is possible to have more difficult texts in a gallery than can be used in some public commission, and at times it is a relief to have a bounded elegant zone in which you can do whatever you can, where you have complete freedom to embarrass yourself or acquit yourself well.

For a gallery show you have to please yourself rather than the obligations of dealing with a larger public not to mention the bureaucracy of public art agencies and local politicians. Is this a liberation or a challenge?

If “please yourself” means to make work that is as it should be, then this should happen in the gallery and in the public sphere.

About liberation vs. challenge, a gallery show is both. Several public projects have taken me a decade or more to complete, and I can be worn down from the negotiations required to realise an honest piece. This process can be especially hard when the subject of a public commission is wrenching and still live. This has been true with anti-memorials in Germany, and was the case with the First Amendment memorial to the blacklisted screenwriters of Hollywood.

An exhibition with a supportive gallerist can seem divine until you remember there is nothing more intimidating than making art for a knowledgeable public, and then there are the impossible standards such as those set by Goya’s black painting. Thinking of Goya keeps me motionless for months, sometimes years on end. Give me a dispute with a local politician any day.

An exhibition with a supportive gallerist can seem divine until you remember there is nothing more intimidating than making art for a knowledgeable public, and then there are the impossible standards such as those set by Goya’s black painting. Thinking of Goya keeps me motionless for months, sometimes years on end

There is a trajectory in the careers of American artists of all generations and genres. The work begins by being small scale, casual, inexpensive and even domestic before success leads to a kind of gigantism.

I don’t think you can make this generalisation about American artists. I am guilty of several big production numbers, but I don’t believe that most US artists are.

In the late 70s you were fly posting handmade posters on the streets. You are now involved in massive sculptural public projects for cities around the world. How has the context and scale changed the nature of your work?

When I must make pieces for large museums with extraordinary architecture, I need to animate those buildings wholly. I use scale so that the art work is not subordinate to architecture, and so that the art joins the strength of the buildings. In the New York and Bilbao Guggenheims, and in Berlin’s Neue Nationalgalerie, I wanted to have my installations describe, rouse and even extend the spaces.

For certain public events, for example when I try to counter a colossal war memorial, my alternative may need to be as large as the “real” monument. Once I had laser texts cover a hulking great Leipzig memorial to insist that the murder and torture of women in war is significant.

While there are reasons for aggressive scale, I flinch when you mention gigantism. It is no love of mine. I have been making xenon projections recently that last a few nights and leave nothing other than a few pictures and recollections, so here’s to the immaterial on the way to the nonexistent.

About context, I continue to depend on and work with, or in opposition to, strong architectural or social situations. That part of my practice is much the same or at least analogous to the old NYC street work.

As a very young artist you used to make abstract stripe paintings; could you ever conceive of returning to such a medium?

No, but I get the stripes back because I often make bands from light.

Over the years you have deployed your texts through a wide variety of media, from paper through stone carvings, metal plaques, laser and LED (Light Emitting Diode) electronic signs. Do you feel certain statements are better suited to a particular media?

Some series, such as the “Inflammatory essays”, are better shown a certain way. The paper posters were prime for these texts, although I occasionally place essays on electronic signs if I need howling.

Or is the intention that they should all be deployed equally in a range of different materials?

The truisms are adaptable and go most anywhere, including on T-shirts. The longer more violent texts are not T-shirt material.

Annette Messager used LED shop front advertising in Paris to display her “Common Proverbs” in 1974 but you were the first artist to really popularise this medium.

I was ignorant of this work. Thank you for telling me about it.

Do you feel these became “signature” works, that people identified them as a “Holzer”?

I suspect that some people think of LED signs and me together. When my daughter was young, she was certain that every flashing display was mine.

I suspect that some people think of LED signs and me together. When my daughter was young, she was certain that every flashing display was mine

If Barbara Kruger ran her text on an LED and you printed your text in the distinctive typeface Kruger is known for, would the work still be identifiably yours?

People probably could tell the difference, but it would be funny to do a taste test.

Is your work the actual text itself or its typographic presentation?

On paper, my work can include the writing, the font, the layout, the choice of ink and more. For electronics or xenon, the art can be the combination of texts, the special effects, the pacing and rhythm, the colour juxtapositions, the choice of site, the placement of vicious, sombre or romantic subject matter in or on buildings with particular histories, functions or shapes.

Would it be true to say that your one and only central medium is language and that it is merely then distributed in a variety of formats and contexts?

No. Language is important because it carries much of the explicit content, but at times meaning also can be conveyed, for example, through the dark plants and flowers of the Black Garden in Germany, or with blood ink, or through a quiet flow of light onto viewers.

You are a voracious reader, especially of political theory and policy journals such as Foreign Affairs. How does this reading filter through into your work, into your own writing?

I read Foreign Affairs for analysis about who is doing what to whom. Then I might write about recent events in the first person to have myself, and perhaps others, emotionally alive to what has happened.

I read much literature in the hope that I’ll begin to write gracefully.

Does the central issue of language make it difficult having to work on foreign projects, for example, using translators such as Anne O’Connor for your Nantes scheme?

Translation always is an adventure, but I can be lucky and have translators who are more literate than I am. Anne O’Connor has worked on translation proper and has helped me communicate with the French Ministry of Justice. She is part of a team amassing texts on law that should play in the Nantes courthouse. Regarding issues of language, it is curious that the Nantes judges rejected a large percentage of the selected writings about justice, and most of these rejected quotations are by long-dead venerated men.

It is curious that the Nantes judges rejected a large percentage of the selected writings about justice, and most of these rejected quotations are by long-dead venerated men

In Britain, advertising has often been amazingly cryptic, abstract and oblique and now even in America it seems to have become much more sophisticated, less overtly “hard sell”. Is it difficult for your own work to maintain its mystery in a media-landscape in which it is increasingly unclear what is being sold or what a slogan is supposed to mean?

What mystery my work has would not be much affected by advertising. The better mysteries are from other sources. I don’t always inhabit the same territory as advertising. My references are more likely to be news or politics. I know what you mean about that ad trend, but now maybe it’s even more mysterious that I am not selling anything. Finally I suppose it’s good every time someone asks herself what is being offered.

There is a great distance, physical and psychological, between the young radical artist of Colab in the East Village of the 70s and the internationally famous artist in her farm compound at Hoosick Falls. Does this distance affect the nature of the work you produce?

Unfortunately, the opposition you set up in your question does not describe a day in the life, then or now. “Internationally famous artist in her farm compound” is not kind, operative or apt. Roughly the same troubles dog me, and approximately the same troubles exist in the world and that is what affects the work.

Is the most important part of your work the solitary creation of the written text or what happens to it afterwards, putting these phrases through the long collaborative process and thus into the public context?

I don’t think it’s possible to rank these activities. I must have the text and the concepts to start, and then it is necessary to present the material to the public with the help of any number of people.

You recently created a monumental sculpture in California in memory of the Hollywood blacklist. How do you feel about working to a specific theme or precise commission?

This always is a puzzle. There is a special obligation to have good answers to such questions. When the history is dirty and completed, when the people have been hurt, when the issue has implications for the present, you must summon a more than adequate response. On any given day it is hard to conjure such a solution and this can make you feel like a worm.

Does a fixed topic or obligatory subject matter compromise the ambiguity so important to your work?

In some projects clarity is necessary. It is clear that the screen writers should not have been blacklisted and persecuted. However, it is improper to represent that time period as simple. A successful memorial admits and tolerates complexity, so this is akin to many of my texts.

On this LA project you worked with a writer Guy Lesser, how do you feel about collaborations with professional writers?

I adore working with professional writers because I am not one. Guy Lesser helped enormously in LA, as did Becca Wilson, the daughter of blacklisted screenwriter Michael Wilson. It was fitting to compose a memorial to writers.

Could you deploy texts written by others and still make them identifiably your own?

Texts for the Los Angeles piece are the First Amendment, attributed quotations from the blacklisted or their families and pro and con citations about blacklisting. There was no reason to make the texts my “own”. I thought that the people silenced should have their remarks cut into stone. For this project I was working as some combination of conceptual artist, a designer and producer. For memorials I now often use signed texts by others.

When you began to work in the late 70s the situation for female artists in America was very different. Do you feel the current cultural climate is inherently far more positive than it was in those days?

I imagine and trust it is better for young woman now, but women in the art world, and especially outside it, do not have equal respect, equal opportunity or equal money.

I imagine and trust it is better for young woman now, but women in the art world, and especially outside it, do not have equal respect, equal opportunity or equal money

On a small-scale political front was the “battle won” by your generation of radical artists?

No, the battle was not won and certainly was not begun by my generation, but I know the situation in art was improved by the output of Cindy Sherman, Kiki Smith, Louise Lawler, Nan Goldin and Rosemary Trockel, to list a few.

What do you consider to be your most successful work to date ?

I don’t know, but I was pleased to have thought of the street posters a long time ago. Since then I have been grateful for installations in buildings such as the DIA, the Guggenheims, Norman Foster’s Bundestag and Mies’s Neue Galerie. I look at the Suddeutsche Zeitung Lustmord piece and the Black Garden. This summer I was happy sitting in the dark with a crowd of people watching xenon in Mexico.

Biography

Background: Born 1950, Gallipolis, Ohio; 1970-71 University of Chicago; 1972, Ohio University, Athens; 1975 Rhode Island School of Design; 1977 Whitney Museum’s Independent Study Program

Currently showing: Jenny Holzer: OH at Cheim & Read, New York (16 October-17 November)

Selected previous exhibitions: 2001: Neue Nationalgalerie Berlin; 2000: Oslo Museum of Contemporary Art; 1999: Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; 1998: Instituto Cultural Itaú, São Paolo; 1997: Museum of Modern Art, New York; 1996: Centre Pompidou, Paris; 1994: Art Tower, Mito, Japan; 1990: 44th Venice Biennale; 1989: Dia Art Foundation, New York; Guggenheim Museum, New York; 1982: Times Square, New York

• To read more of our best artist interviews over the past 30 years, click here for the full collection