Las Vegas

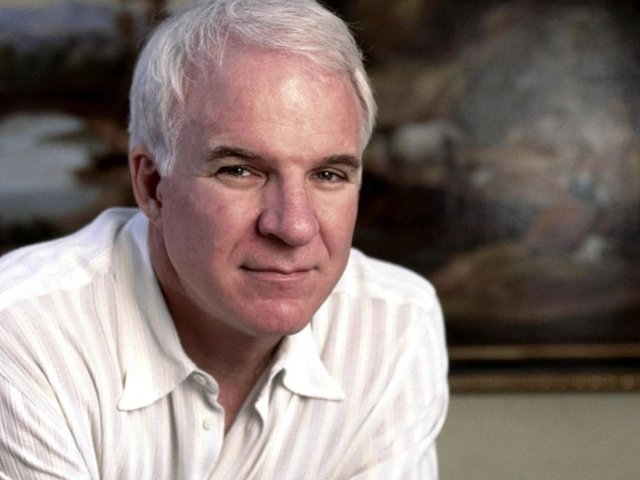

When I was growing up in Las Vegas in the Seventies, I had a friend whose father bore a strong resemblance to Steve Martin, and people would often stop him to ask if he was the man himself. This was a plausible question because the famous comedian often came to town to perform in hotel showrooms.

In 2001, I only visit Vegas to visit my family. The city, like its old casinos, has been imploded and rebuilt many times over. And the Steve Martin act that now appears in Vegas is not the man himself, but his art collection, which is on view publicly for the first time, at the gallery of the Bellagio Hotel.

Steve-Martin-as-art-collector is not news to many in the art world, but for the average visitor to Vegas, "art collector" would not be the first association they would make with a man who became famous as a quirky comedian, eternally satirising the American Way, strutting across stage and calling himself "a wild and crazy guy." This exhibition of 28 pictures seems intent to give both of those groups something to digest.

Martin’s taste runs to figurative paintings and works on paper, with a heavy emphasis on the kind of American 20th-century art that looks big and bright at first, then dark and mysterious only on longer contemplation. In some instances, this juxtaposition is evident in two separate paintings, such as the pair of Edward Hopper canvases—"Captain Upton’s House," a solid, white, lighthouse admidst a blue sky painted in 1927; and a later composition of an older woman, gazing into the night in "Hotel window", 1955.

In other cases, the contrast appears simultaneously in the same work, such as in Martin Mull’s painting "Birthday boy XI", 2000, which presents a sun-kissed, innocent boy gushing with happiness at his birthday, seemingly unaware of the half-naked mother- and sister-like figures offering cakes around him. While the exhibition includes such obviously famous work as Roy Lichtenstein’s "Oh...alright..." from 1964, it also shows that Martin collects artists whose names are not as clearly carved in the popular canon; for example, the traditionally inclined Sixties painter John Koch, represented by two interior scenes.

Several European works from Martin’s collection are also being shown, complementing the themes and movements introduced by the other pictures; for instance, a David Hockney backyard swimming pool, minus people but with splash, fits well with the Fifties nightmare that is Eric Fischl’s "Barbeque". Picasso’s reclining, odalisque-like pencil drawing from 1919, and a pair of muted Georges Seurat crayon scenes of a woman reading and a man on a terrace from 1883 and 1884 from the Bergruen Collection (which Martin says he first saw on view at the National Gallery in London) are nice to see juxtaposed with a Cindy Sherman monochromatic film still in which she, clad in lingerie, looks at her reflection in the bathroom mirror.

If one of the most enjoyable ways of viewing a private art collection is in the home of the collector, then an audio guide, complete with the collector’s personal anecdotes, might be the best alternative. When Steve Wynn first opened the Bellagio Hotel and installed his own collection of multimillion-dollar Impressionist and Modern paintings, he endowed the gallery with a set of Wynn-narrated audio guides included in the price of an admission ticket, leaving the walls free of lengthy text panels. Wynn’s arrangement, while perhaps a little unorthodox—you had to pay to see the show, but if you had enough money, you could negotiate to buy one of the said masterworks—gave the gallery a personalised feeling, a precedent that has remained even as the gallery has changed hands and business plans.

Steve Martin, an entertainer to the end, uses the audio guide to characteristic effect. Enlisting the help of the estimable Adam Gopnik, a writer for the New Yorker, Martin has added much of the irreverent personal detail that makes the exhibition something other than a browse through nice art. In one note on a work by Vija Celmins, Martin begins, "I’m always frustrated when I read an artist’s name and have no clue as to its pronunciation. Usually the only way to find out is to embarrass oneself in front of wiser company and stand corrected. So I'll give it to you straight off: VEE-ah SELL-mens. Now let’s go have lunch." But in this joke about a mouthful of sound, isn’t Martin actually really inviting you to lunch—to feast on art? Like a classic composition, the show rests on a triangle of activity—in this case represented by three F’s: funny, frank and facetious—a little like everything else Martin has created.

“The private collection of Steve Martin: from Piacsso to Hockney”, (until 3 September), The Bellagio Gallery of Fine Art, Las Vegas, Tel: +1 888 488 7111, www.bellagio.com

Originally appeared in The Art Newspaper as 'The man who mistook his art for an act'