The Tate Modern in London and the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis have organised an exhibition that has wrestled an established Italian art movement away from its “inventor” and its country of origin in an attempt to uncover its roots.

“Zero to infinity: Arte Povera 1962-72” (31 May-19 August) is the first major museum show of Arte Povera works for well over a decade and the first ever in the UK. One of the last important Arte Povera overviews outside Italy in recent memory, “The knot” in 1985, was confined to one of New York’s alternative art spaces, the P.S.1 in Queens, over the river, and a world away, from Manhattan’s Museum of Modern Art.

The Tate exhibition brings together 140 works (including a number of works on loan from private collections which have not been seen since anywhere since the 1960s) by 14 artists: Giovanni Anselmo, Alighiero Boetti, Pier Paolo Calzolari, Luciano Fabro, Piero Gilardi, Jannis Kounellis, Mario and Marisa Merz, Giulio Paolini, Pino Pascali, Giuseppe Penone, Michelangelo Pistoletto, Emilio Prini and Gilberto Zorio.

Many of the artists in the current Tate show took part in the early landmark group shows of Arte Povera: Harald Szeeman’s touring exhibition, “Live in your head: when attitudes become form”, which began at the Kunsthalle Bern in 1969, and Germano Celant’s “Conceptual art, Arte Povera, Land art” show of 1970 in Turin.

The name given to the disparate grouping of artists from Turin, Rome, Milan, Bologna and Genoa originates from a 1967 catalogue essay and a corresponding article in Flash Art magazine titled “Arte Povera: notes for a guerrilla war”, by a young, influential critic of the time, Germano Celant, now roving curator for the Guggenheim and the Fondazione Prada. The terminology Celant used to describe his chosen artists was loosely based on a theory formulated by the Polish theatre director, Jerzy Grotowski, who proposed a pared-down style of confrontational drama, which he later published in a book, Towards a poor theatre, of 1968.

As a gesture of courtesy, the curators of “Zero to infinity”, Richard Flood from the Walker Center and Frances Morris from the Tate, sought Celant’s “blessing” (which they received by exchange of letters) before embarking on their own, artist-oriented history of Arte Povera.

In attempting to start from zero, by backdating the dateline of the show to five years before the movement was baptised, and without Celant for guidance, the UK and US partnership risked alienating some of the senior practitioners of Arte Povera, such as Jannis Kounellis and Gilberto Zorio, who would have preferred their work beyond the 1960s and 70s to be included as well.

In fact, since the formalisation of Arte Povera in the early 1970s, Germano Celant and many of his Povera protegés have preferred to exhibit work under the artists’ individual names, both to differentiate them from the Arte Povera tag and to allow them to develop independently.

For this ambitious survey, which will tour the US until 2003 after leaving London, both curators had head starts as both had worked with many of the artists before. The Walker Art Center was the first US museum to show and collect Arte Povera artists such as Mario Merz, from as early as 1966. The curators were also helped by critic and curator, Francesco Bonami of the Chicago Museum of Contemporary Art, a native Italian speaker who introduced them to many of the artists.

In a fresh interpretation of Arte Povera’s genesis, “Zero to infinity” proposes shows by Michelangelo Pistoletto in Turin and Pino Pascali in Rome in 1962-63 as signifying the first wave of the movement, some four years before the group shows cited in Celant’s book Precronistoria, which gives his account of the “prehistory” of Arte Povera.

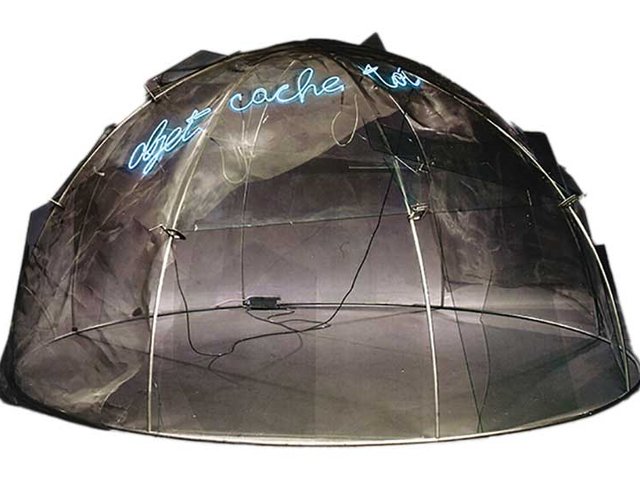

Whatever the year of origin, Arte Povera artists indisputably share a use of humble materials (even the marble in Fabro’s “Feet” can be seen on any pavement in Milan), and they made no attempt to dress them up as anything more than blocks of ice, planks of wood, lumps of lead, lettuce leaves or paper doilies.

The exhibition goes further, however, than the mere use of materials to elucidate the disputed meaning of Arte Povera, which resists being translated as simply poor, impoverished or pauvre. One argument goes that the artists were all linked by their political motivations. Indeed, the 1960s were genuinely volatile and transitional times for Italy, with student demonstrations and social unrest of which the artists were certainly aware, especially those affiliated with Gian Enzo Sperone’s second gallery which shared a building with party headquarters.

A political interpretation of art often arises after the event, however. It is easy to give a fascist reading to Fabro’s “Golden Italy”, a cut-out of a map of Italy, hung upside down like Mussolini, or see Pino Pascali’s fake machine gun as a call to arms. But Pascali thought that the 1968 Venice Biennale (which included his own work) should go ahead, despite the boycott by fellow artists, a view he explained away in a manifesto, stating that “artists have always been victims of politics”.

The real political thrust of Arte Povera was an aggressive opposition to the cult of art as a luxury commodity. None of the early works was produced with a sale in mind. Many were huge and unwieldy, others were one-off performances or conceptual pieces. But, as nearly always in the history of the Avant-Garde, the Arte Povera artists were well championed by a few influential critics, galleries and dealers such as Ettore Sottsass, Ileana Sonnabend and Gian Enzo Sperone, and their works were rapidly to rise in value.

“Zero to infinity: Arte Povera 1962-72” (31 May-19 August), Tate Modern, Bankside, London Tel: +44 (0) 20 7887 8700. Touring to Walker Art Center, Minneapolis (13 October-13 January 2002); Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles (10 March-11 August 2002); Hirshhorn Museum, Washington (17 October-12 January 2003)