Dürer’s vandalised “Virgin of Sorrows” briefly went on show at Munich’s Alte Pinakothek last month, ten years after it was subjected to an horrific attack. Concentrated sulphuric acid was thrown at the Virgin’s head, and it immediately dripped down her blue gown, stripping away the paint and exposing the white ground. The Munich curators had a long debate on whether to show the damaged work, and eventually a compromise was agreed: the “Virgin of Sorrows” would be shown only for the first fortnight of the ten-week Dürer exhibition. The rest of the exhibition runs until 14 June.

“The ‘Virgin of Sorrows’ will be a terrible shock for visitors, and this was a reason not to exhibit it. But the damage is a fact, and it will always remain even if it is hidden by the restorers. So we decided to put it on show for a short period”, explained curator Dr Martin Schawe. The exhibition also includes the two other Dürer masterpieces which were victims of the 1988 attack, the “Paumgartner altarpiece” (a Nativity, with wings of St George and St Eustace) and the “Glim Lamentation”. Following 23,000 hours of work, these two pictures have now been successfully restored, and were unveiled for the show. Work on the “Virgin of Sorrows” will begin shortly, financed with a substantial donation from businessman August von Finck.

It was on 21 April 1988 that Hans-Joachim Bohlmann, a fifty-one year old Hamburg man, arrived at the Alte Pinakothek and headed for the Dürer room. He started throwing acid from two bottles at one of the altarpieces, and when some schoolchildren who were in the room tried to intervene, he warned them off with the acid. Some of the Dürers were behind glass and were safe, such as the magnificent self-portrait, but Bohlmann succeeded in causing terrible damage to three works. He then allowed guards to seize him. Bohlmann was discovered to be mentally unstable and it later emerged that he had been responsible for a long string of incidents.

He was placed in a secure hospital, but in January this year he was allowed out for a few hours and escaped. He made his way to Dresden. The Gëmaldegalerie includes Dürer’s “Seven Sorrows of the Virgin”, of which Munich’s “Virgin of Sorrows” once formed the centrepiece. Curators and warders in a number of German galleries now carry photographs of Bohlmann in their wallets.

Immediately after the 1988 attack, restorers arrived in the Dürer room within three minutes. The acid quickly penetrated through the paint. The surfaces of the three works were covered with a dark, foaming and malodorous liquid. The restorers removed the panels from the walls, placing them face upwards on the floor to prevent further dripping.

Hours later the panels were removed to the restoration studio, and action was taken to deal with the pools of acid which had accumulated at the bottom of the panels, just above the frame. The acid had already soaked into the end-grained wood, which was beginning to degrade into a black, slimy mass at the edge. Small areas of the damaged wood were removed with a fretsaw. This resulted in losses of up to one centimetre into the wood at various points across the bottom of all three paintings.

According to Chief Restorer Bruno Heimberg, the damaged surface of the paintings consisted of “friable, very porous, partly crumbling, lava-like crusts of a reddish brown to light grey colour.” The exposed gesso ground ranged from extremely porous to powdery.

The most difficult challenge for Mr Heimberg and his colleagues at the museum’s Doerner Institute was how to neutralise the concentrated sulphuric acid. Diluting it with water would have spread the damage. So too would the application of neutralising agents, which would have caused foaming.

It was decided to try a technique which was new in picture restoration, the ion-exchange method. In this chemical process, the sulphate anion is exchanged with a carbonate, forming carbonic acid in an aqueous solution. This immediately decomposes into carbon dioxide and water. The process is undertaken by delicately applying the agent in the form of a resin. Work on neutralising the acid on all three pictures took a year.

The next problem was restoring the lost areas. The losses were filled with wax-chalk. Retouching was then done using modern powder paints, bound with synthetic resin (with oil paint occasionally used in the glazes).

“Our aim was to close the gaps, and make it difficult to see the retouches”, explained Dr Schawe. Getting the right effect was particularly difficult because the pictures were all covered with darkened varnish, which was retained. To have removed this varnish would have created additional problems. These retouchings are not immediately obvious to the casual visitor, although they can easily be spotted when seen close up, particularly at an angle.

This approach differs considerably with that taken by restorers at the Hermitage after Rembrandt’s “Danaë” was vandalised in an acid attack in 1985 (The Art Newspaper, No.60, June 1996, p. 4). At the Hermitage, the acid was neutralised by washing the canvas with water. After much debate, museum restorers decided to make their repainting clearly visible.

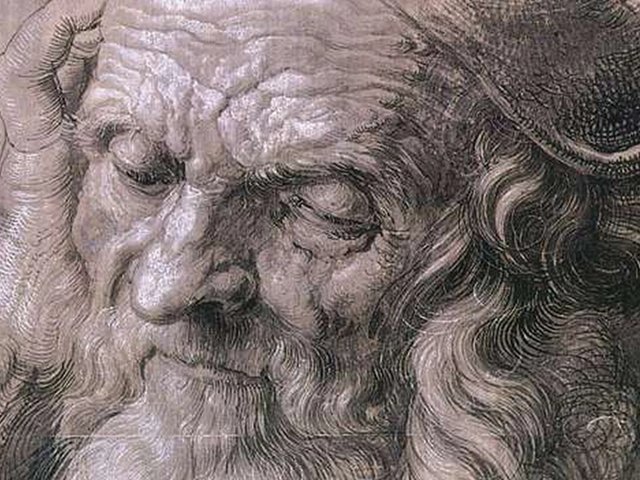

One of the positive spin-offs of the Munich work is that all the Alte Pinakothek’s Dürers have been thoroughly examined, and the results published in the exhibition catalogue. The paintings have been subjected to infra-red reflectography, which has revealed that Dürer did much less underdrawing as his career progressed. The changes are particularly apparent if one compares the detailed underdrawing of drapery in the “Virgin of Sorrows” (1495-8) with the much sketchier underdrawing of “The four Apostles” (1526). In all his works, there is relatively little change between the artist’s underdrawing and the final painting, suggesting that Dürer had very clear ideas when setting out on a work.

Dürer’s pigments have also been closely examined, and compared with those used by his contemporaries. An analysis of fifty-six South German paintings of the period showed that ultramarine, made from lapis lazuli, was only used by two artists, one of which was Dürer (in his “Suicide of Lucretia” of 1518). By this time Dürer was highly successful, and able to afford the finest pigments. Throughout his career Dürer was meticulous about his materials, and it has been found that he sometimes used a ground made from egg shells, which gives a much brighter white than normal chalk.

To show the results of the restoration work, the Munich Pinakothek is exhibiting the three damaged pictures (two restored and one unrestored) with its seven undamaged Dürers and three works which are normally on loan to Nuremberg’s Germanisches Nationalmuseum (“Hercules” and “Portrait of Wolgemut”) and Augsburg’s Staatsgalerie (“Portrait of Jakob Fugger the Rich”).

The exhibition is at the Neue Pinakothek (the Alte Pina-kothek is closed for renovation work). When the exhibition finishes, the Dürers will be transferred across the road to the Alte Pinakothek for its reopening on 31 July. There the pictures will be on display in the gallery’s traditional Dürer Room, all of them protected by glass.