“I have chosen seven men whose personalities will, I hope, interest other people as much as they have intrigued me. I do not think that I have fantasticated them, but time always supplies some element of fancy. We should remember L.P. Hartley’s, ‘The past is a foreign country. They do things differently there’”

J. Paul Getty

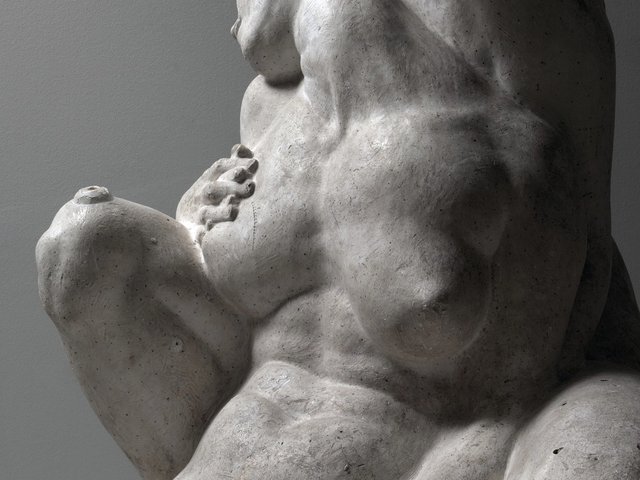

He moved to the door saying, “If Mr Colin recommends them, I’ll take all three”Despite, or perhaps because of, the disparity in their characters and backgrounds, Colin Agnew and Paul Getty became close friends. Their conversation had one interesting phonetic feature. Mr Getty, by omitting the letter “i”, reduced Colin’s Christian name to a monosyllable, while Colin contrived to get three separate sounds into the name Paul, which he always spoke with a rising inflexion. Mr Getty bought Sutton Place in the 1960s, and this was the period when he most enjoyed acquiring pictures. The vast rooms of that great Tudor mansion allowed him to indulge his taste for really large canvases, and the full-length portraits by Gainsborough and Batoni, the enormous hunting scenes and game larders by Snyders, and a life-size nude by Palma Vecchio all looked wonderful in their new setting. At this date he rarely bought without consulting Colin, but as neither man had any real sense of time, their meetings required considerable stage-management. At a lunch party celebrating Colin’s ninetieth birthday, Mr Getty arrived half an hour late with the ingenuous excuse that he had miscalculated how long it would take him to walk from the Ritz to Boodles Club in St James’s Street.

Once, in Colin’s absence, I showed him three pictures which he was considering: a portrait by Veronese; another by Tintoretto and the centre panel of an altarpiece by Girolamo di Benvenuto. Asking for the appropriate volumes of Bryan’s Dictionary of Painters, so that he could study the entries for these artists, he read slowly through them marking the place he had reached in the text with his forefinger. Eventually, thunder rumbled in the distance, and he looked up and asked if it was gun-fire; when I said I thought not, he moved to the door saying, “If Mr Colin recommends them, I’ll take all three”. Feeling that further conversation was needed, I asked what the roses were like at Sutton that summer. He said that they were “just fine”, and, taking out a notebook, made an entry. A year later, I received a letter inviting me to lunch so that I could come and see his garden. I am glad to have had the chance to record this act of kindness on the part of a man who is more often remembered as having installed a pay-phone for the use of his week-end guests.

The Reverend E.P. Baker

His arrival in Bond Street with chips of frozen snow still clinging to his person recalled that epic picture of polar heroism, “A very gallant gentleman”, in which Captain Oates staggers out into the blizzard

The most loyal visitor to the private views of our Annual Watercolour Exhibitions was the Reverend E.P. Baker, the rector of a small parish in the depths of Oxfordshire. Although a member of another faith, his small, slightly portly figure and twinkling spectacles recalled Father Brown. He had, too, the rock-like character and physical courage of Chesterton’s priest. Punctual arrival at the head of the queue which formed up by 9:15 on the January Monday morning meant for him rising in the small hours and manoeuvring a moped along frozen lanes to catch the milk train from Kingham to Paddington, but he never failed to appear. In the grim winter of 1963, snow drifts blocked his way to the station and, as often happened in that Siberian season, the train’s heating system had broken down. His arrival in Bond Street with chips of frozen snow still clinging to his person recalled that epic picture of polar heroism, “A very gallant gentleman”, in which Captain Oates staggers out into the blizzard. The queue, with whom he was a great favourite, set to work to defrost his outer clothing while we from inside sent out a nip of something warming for the inner man. By common consent he was then allowed first choice in the Exhibition, and had soon made his annual purchase of two drawings, and returned to his normal rosy self.

Ephraim Shapiro

The fullest enjoyment of Giorgione’s altarpiece could, he claimed, only be realised if we had walked from Venice to Castelfranco.

Another of our clients who thought that the pleasure we derive from works of art increases in ratio to the difficulties we experience in arriving in front of them, was a Russian emigrant who had started his career in the Hermitage Museum. The fullest enjoyment of Giorgione’s altarpiece could, he claimed, only be realised if we had walked from Venice to Castelfranco. Ephraim Shapiro worked in London in the Russian department of the B.B.C. Wartime conditions suited this complicated man, as he suffered from chronic insomnia and liked fire-watching by night while emerging in daylight to make predatory raids on the thinly attended sale-rooms which provided a happy hunting ground for someone with eyes as sharp as his. His conversation had the inconsequence that Chekhov gave to his older characters and it was larded with Russian proverbs, many of which he was suspected of having invented himself. There was, however, nothing phony about his powers of connoisseurship, and looking at pictures with him was fascinating. Struwwelpeter hair streaming behind him, he took exhibitions at the run, a manic smile of glee overtaking his features when he spotted a wrong attribution. He had the Russian love of obfuscation, and indulged it to the full in his will, in which he left several pictures to the Hermitage. As he had become an English citizen and relations between ourselves and the Soviet Union were, when he died, a great deal pricklier than they are today, this caused considerable suspicion and distrust among the fiscal authorities of both countries. He would have relished the confusion which must have arisen.

Paul Wallraf

Marriage gave a new thrust to Paul’s collection. He now bought figures of animals and birds in every conceivable medium from bronze and terracotta to ivory and jade. (Sotheby’s entitled a section of his posthumous sale catalogue “The Wallraf Menagerie”.)

Paul Wallraf had a wonderful eye, widely ranging tastes and the acquisitive instinct of a magpie. He could rarely resist buying anything he liked even though he had nowhere to put it. Descended from Ferdinand Franz Wallraf, who with Johann Richardt had founded Cologne’s great museum, Paul lived in what was for post-war days a sizeable apartment with large rooms. They soon proved to be far too small to contain his collection. Visits, though immensely enjoyable, had elements of both the obstacle race and the assault course. There was simply nowhere to put down one’s drink or, eventually, anywhere to sit. Objects of all kinds occupied every inch of space and the walls were so thickly hung with pictures that smaller drawings lay flat or propped against their neighbours. Just when it seemed he would be evicted by his collection, the flat immediately above became available, so he took it and started collecting all over again. Then Lebensraum became available in Venice in the Sixties, when he took on the first floor of the Palazzo Malpiero Trevisani in Campo Santa Maria Formosa. Shortly after Paul acquired this Venetian outpost, Carlo Bestegui died and a sale of his collection was held in the Palazzo Labia. The Italian government, concerned that the better things should remain in Italy, were delighted to hear that many of them only made the journey by canal from the Cannareggio to the piano nobile of the Palazzo Malpiero. Paul made a very happy marriage with Muriel Ezra, the widow of a distinguished zoologist, who built up his own private menagerie in Surrey in the days before safari parks proliferated in the English countryside. Pre-war south-bound motorists may still remember, soon after leaving the Kingston by-pass, being stared at by supercilious llamas and ruminant bison from a field on the left which was the boundary of the Ezra estate. Marriage gave a new thrust to Paul’s collection. He now bought figures of animals and birds in every conceivable medium from bronze and terracotta to ivory and jade. (Sotheby’s entitled a section of his posthumous sale catalogue “The Wallraf Menagerie”.)

Paul and Muriel entertained lavishly and were much loved in Venice. Every morning throughout the summer they would march smartly from their capanna at the Albergo Excelsior to the Hôtel des Bains at the other end of the Lido. There they would touch the boundary fence and march smartly back again. This daily parade assumed for the bagnini something of the significance that the Changing of the Guard has for London’s tourist guides. From the Regatta to the Fireworks, Venice has always laid on regular spectacles for her visitors, and here was a new one.

Sir Ralph Richardson

I noticed that when particularly struck by a drawing, his features would assume the same look of wide-eyed amazement that they had done in the latter rôle when Bottom wakes from his dream and begins the speech, “I have had a most rare vision ...”

Sir Ralph Richardson rarely missed our Watercolour Exhibitions. His favourite artist was John Varley. He usually arrived on a powerful motor bicycle—a B.M.W., I am told. Once he brought another famous theatrical knight on the pillion. It was fascinating to hear, as they removed their crash-helmets, the beautifully modulated tones of the greatest Hamlet of our century enunciate the words, “Ralph, dear boy, you really do drive much too fast”.

Richardson’s enthusiasm made his visits great fun, but he could be brusque. When I said how much I had enjoyed his performance in the title role in Uncle Vanya, he snorted, “Oh, did you. I could not understand the fellow at all myself”, and stumped away. Fine clocks were another of his many passions. Asked by his doctor if he had recovered from flu, he said that he was fine but one of the clocks was going badly, and would the doctor come and have a look at it as soon as it was possible. For our generation he was incomparable in two parts—Falstaff and Bottom the Weaver. I noticed that when particularly struck by a drawing, his features would assume the same look of wide-eyed amazement that they had done in the latter rôle when Bottom wakes from his dream and begins the speech, “I have had a most rare vision ...”. Was it, I wondered, his natural reaction to something extraordinary, and did he therefore use it on the stage, or was he simply acting and registering what he thought was the appropriate emotion under the circumstances? I doubt if he knew himself.

Frits Lugt

He had a healthy Dutch appetite. After lunching with Général de Gaulle, his diary recorded, “uninteresting pictures, dull guests and no second helpings”

A warning flashed across Europe in 1907 when Max Liebermann wrote from Amsterdam to Dr Bode in Berlin, “There is a red-headed young man here whom we must watch”. This “rothaariges Jungling” was the twenty-three year-old Frits Lugt who was then working for the auctioneers Frederik Müller et Cie and the message led to an invitation to visit Dr Max Friedländer in that great training ground for art historians, the Print Room of the Kaiser Friedrich Museum. Lugt’s arrival in Berlin coincided with that of Colin Agnew, whom we had sent to open a branch there, and the two men, almost exact contemporaries, became lifelong friends. Mr and Mrs Lugt were to put together one of the most fascinating collections of the next sixty years. They were amateurs in the eighteenth-century sense of the word. They amassed shells, English portraits, Indian miniatures, blue-and-white china and artists’ letters with the same degree of expertise with which they collected pictures, drawings and prints. Mr Lugt died on Rembrandt’s birthday, and was, like the artist, a Mennonite. He seemed austere and I never saw him with a hair out of place, or a button undone, but he had a healthy Dutch appetite. After lunching with Général de Gaulle, his diary recorded, “uninteresting pictures, dull guests and no second helpings”. At our first meeting I was nervous, remembering the glacial formality of a visit to Berenson at I Tatti, but they order things differently in the rue de Lille. He greeted me with scrupulous courtesy and a welcoming smile. During a two hour tour of his collection, he imparted endless information. He was then in his late seventies, but I think he only sat down once. It was an unforgettable Master Class. When I thanked him he said, “Please come again. We always have time for people who like to use their eyes”. I walked home on air across the Esplanade des Invalides and bored everyone with his parting words for weeks afterwards.

Ralph Edwards

There lurked in his character, as with all the best Welshmen, an element of Dylan Thomas’s “No Good Boyo”, and his conversation was designed to provoke, particularly in political matters about which he felt strongly.

Shakespeare must have known someone very like Ralph Edwards when he put Fluellen into Henry V. If Ralph came in on St David’s Day, I would have hidden to avoid being forced to eat a raw leek as was poor ancient Pistol in that play. At all other times, Evelyn and I rushed out to meet him if we heard that he was in the Gallery, so stimulating was his company. We were told that a recurrent illness had made him in his earlier days an abrasive and difficult colleague but when we knew him, the right pill had been found and the former angrily flashing eye and rasping voice of which people spoke had mellowed to a genial twinkle and an infectious chuckle. There lurked in his character, as with all the best Welshmen, an element of Dylan Thomas’s “No Good Boyo”, and his conversation was designed to provoke, particularly in political matters about which he felt strongly. His knowledge of English furniture was legendary, but he had too a sharp eye for pictures. Appropriately, he was one of the first to appreciate the work of Richard Wilson’s fellow countryman and contemporary, Thomas Jones. Long before the rest of us, Ralph had recognised the quality of those intimate plein air sketches of Welsh valleys and sunlit Neapolitan walls, today so sought after and so expensive. When his book Early Conversation Pictures appeared, Evelyn took what Henry James would have called “the rash and insensate step” of saying that he was enjoying it. “How far have you got?”, asked Ralph with a look of deep suspicion. Evelyn admitted to only having read one chapter. “Ah”, snorted the author triumphantly, “then you still have another 160 pages of closely packed erudition to come”. He was a well-read man, admiring especially the mystic poetry of Henry Vaughan, the Silurist who came from the Brecon country of the Black Mountains where he himself had a house. It was said of Vaughan that he was “esteemed by scholars, an ingenious person, but proud and humorous”. It could have been said of Ralph too.