When Nona Faustine learned about the history of slavery in New York, a “lid was blown off”, she says. Born and raised in Brooklyn, the photographer was familiar with the colonial names that adorn the city, but she was not aware of its deep ties to slavery. As Faustine researched this history, she began photographing herself in places linked to enslavement, often posing nude—apart from a pair of white “church lady” shoes, a nod to the use of clothing to assimilate and signify decorum.

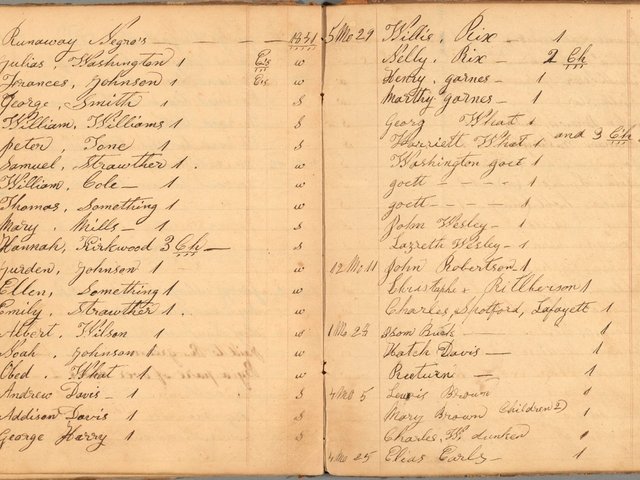

Many are familiar sites, such as Wall Street, the beacon of commerce that was named after the defensive wall built by slave labour and the site of public slave auctions between 1711 and 1762, as well as the nearby Tweed Courthouse, which was constructed along the African Burial Ground—the largest colonial-era cemetery for Africans, which was rediscovered in 1991.

Nona Faustine, They Tagged the Land with Trophies and Institutions from their Rapes and Conquests, Tweed Courthouse (2013)

© Nona Faustine

This series of more than 40 photographs made between 2012 and 2021 comprises the artist’s first solo museum show, Nona Faustine: White Shoes, at the Brooklyn Museum. Speaking from her studio in Brooklyn, Faustine reveals how evidence of this erased and forgotten history lies in plain sight.

The Art Newspaper: When did you first learn about New York’s history of enslavement?

Nona Faustine: I started learning about it in grade school. The message was that slavery occurred here, but it was very limited in scope—that we didn’t have many slaves and we were a free city. It wasn’t until I was in college and saw the excavation of the African Burial Ground that the lid was blown off about the true history, which is that we were heavily invested in slavery in New York City. We had one of the largest populations of enslaved people outside of Charleston, South Carolina.

To see, understand and have conversations about the legacy of enslavement in areas just outside the Brooklyn Museum, it’s like blinders are taken offNona Faustine

Once you know the history, you see it everywhere. There are colonial houses owned by slave owners everywhere. All you need to do is look up the early Dutch settlers: Wyckoff, Lefferts, Van Cortlandt. Their houses are still here, and there are streets and parks named after them all around the city.

These sites are inextricably linked to history.

Exactly. I reference this in some of the titles, like the quote from Harriet Tubman’s biography: There are few markers left but your black body is the marker. The land does hold the memory of your existence. You only have to put it there in its natural state to remember. Harriet Tubman, Sylvester Manor, Shelter Island, NY (2021). This land and our nation have not healed from slavery. In Prospect Park, Brooklyn, there are Revolutionary War soldiers in unmarked graves. Under the sidewalks in Lower Manhattan, there are unidentified bodies from the African Burial Ground. When the city does construction, they have to face this, but other than that, we don’t talk about it.

Isabel, Lefferts House, Prospect Park, Brooklyn, NY (2016), from Nona Faustine's series White Shoes © Nona Faustine

Can you share more about how you title your work? You include reflections on the past and future of a site, as well as one contemporary reference to the killing of Sandra Bland.

A lot of the titles are influenced by literature and poetry, and others give information about the site. Some name the enslaved people who lived in the places I photograph. I see titles as a part of the art. I included Sandra Bland because she was killed when I was making this series, and her death spoke to the generations of violence against Black women in this country.

You are nude in some images, particularly in the beginning of the series, but you always have on the white shoes. Can you explain their symbolism?

The shoes are at the core of the series. I’m unclothed in the beginning to make people see me and understand that the first images are at the beach along the Atlantic Ocean, because that’s how Africans were brought to this country. I remain unclothed on Wall Street standing on a false slave block. I am not playing a slave, but I am standing there and have on shackles to make you understand what that could have looked like.

How did the public respond to seeing you nude?

No one bothered me at all. It was amazing. My body had a lot of power. There was a moment on the steps of the Supreme Court, when I took off my coat and revealed my nudity and a man walking by and gasped. I felt very empowered. New Yorkers are used to seeing people doing photo shoots, so they try not to pay attention. I also think they didn’t want to look at me in that state: nude, Black woman, plus-sized. That’s what I would guess their reactions were about. It was almost like I was invisible.

What have the reactions been from the public since your exhibition opened?

There’s inevitably some backlash, but the response is always incredible to this body of work. The power of photography lies in the conversations it opens. It introduces a world that people might never have heard of. To see, understand and have conversations about the legacy of enslavement in areas just outside the Brooklyn Museum, it’s like blinders are taken off. That, for me, is the goal of the work. Every day, we walk through sites attached to slavery. I want people not only to remember me, but to remember the faces and the names of people lost to history. That’s what people fear in death: that they’ll be forever forgotten. As long as we hold the memory of them, they will never die.

• Nona Faustine: White Shoes, Brooklyn Museum, New York, until 7 July