The Harlem Renaissance is one of the most significant cultural movements that emerged in the early decades of the 20th century in the US, with Black artists, writers, musicians and thinkers engaging in self-expression with pride and creativity. Although New York City was a nexus from the 1920s to the 1940s, the Great Migration led to millions of African Americans moving out of the segregated South and forming communities across the country with their own vibrant artistic scenes in Chicago, Philadelphia and beyond. Despite the movement’s enduring impact on culture, including on the international development of Modernism, its artists were long overlooked by major museums, both in collecting and in exhibitions.

This persistent oversight reached a flashpoint in 1969, when New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art (the Met) opened the exhibition Harlem on My Mind, which failed to include any Black painters or sculptors. Protests ensued, as the show disregarded the pivotal role of artists in the activism and community of Harlem, instead focusing on reproductions of newspaper stories and photographs. Although photographs by James Van Der Zee and Gordon Parks were shown, they were treated as documentation rather than fine art (photography would not have its own independent curatorial department at the museum until 1992). The Black Emergency Cultural Coalition, organised in response to the exhibition, gave out leaflets at the museum stating: “If art represents the very soul of a people, then this rejection of the Black painter and sculptor is the most insidious segregation of all.”

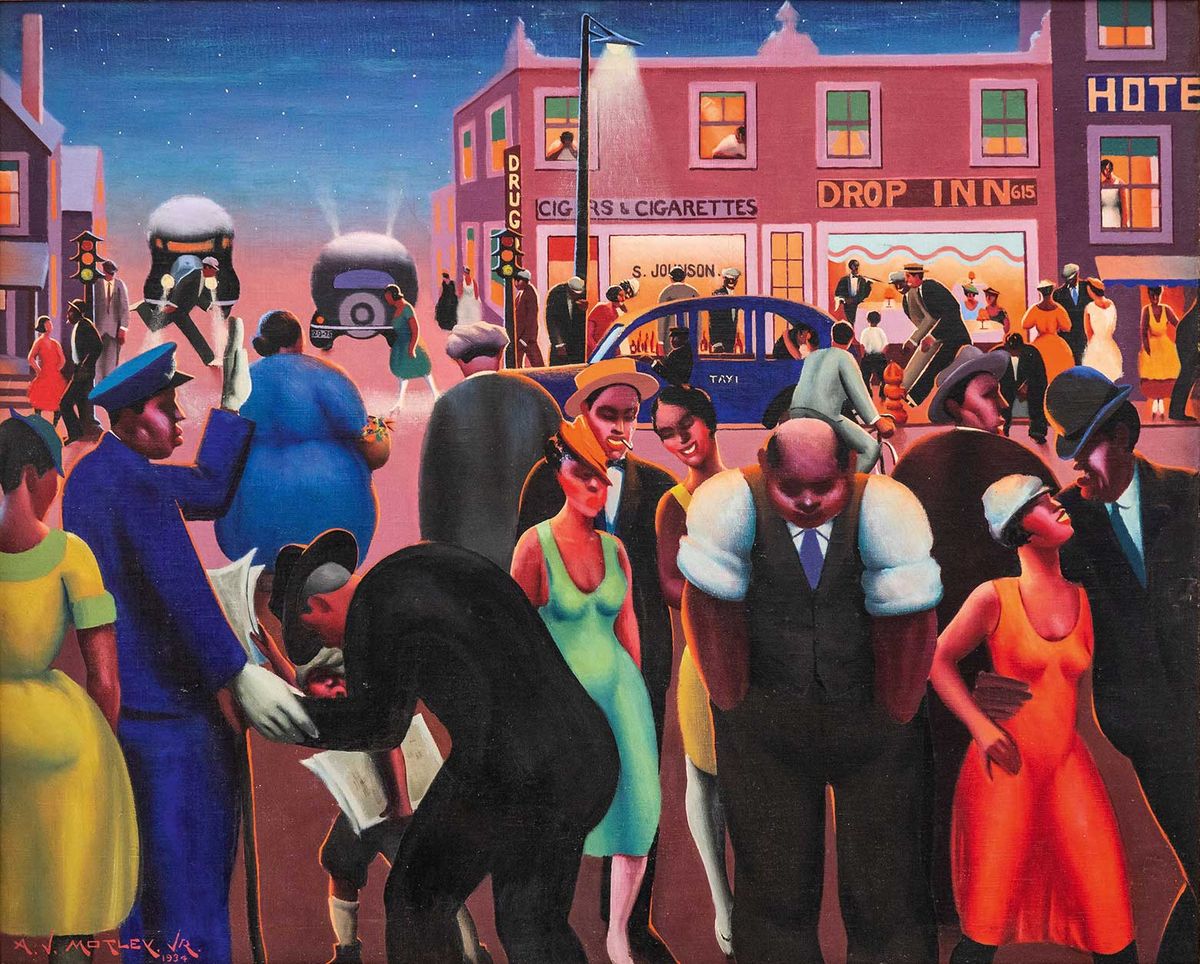

The Met's new exhibition, The Harlem Renaissance and Transatlantic Modernism, is only the fourth museum survey on the era and the first in New York in almost four decades. It also reflects the Met’s shift over the years in both bolstering its collections with important inclusions like the James Van Der Zee Archive (established in 2021 with the Studio Museum in Harlem) and diversifying its curatorial leadership. The show presents around 160 works of painting, sculpture, photography, film and more by artists including Aaron Douglas, Archibald Motley Jr, Augusta Savage and Laura Wheeler Waring.

Shifting the gaze

It was the lack of institutional attention to the Harlem Renaissance in the past that, in part, compelled the curator-at-large Denise Murrell to begin organising the exhibition soon after she joined the museum in 2020. “The Harlem Renaissance has not been integrated into the central narratives of early 20th-century Modern art,” Murrell says. “And that applies whether we’re talking about American art or the international context. So I was feeling that this was a real void, and it’s such a rich period of radically new thinking.”

The exhibition’s advisory committee includes Mary Schmidt Campbell, who co-organised the 1987 show Harlem Renaissance: Art of Black America at the Studio Museum, and Richard J. Powell, who co-organised the 1997 touring survey Rhapsodies in Black: Art of the Harlem Renaissance. The Met’s outreach to scholars, private collectors and other institutions included several Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs), with a large percentage of the loans arriving from their collections.

“The concentration of art is at the HBCUs, which were one of the few opportunities for these artists to be able to support themselves as artists, to be teachers and to found art schools,” Murrell says. She notes that Clark Atlanta University, Hampton University, Howard University and Fisk University all have robust collections on the Harlem Renaissance, but because of a lack of funding compared to larger institutions, these are often not digitised. In travelling to the HBCUs, she was able to examine their works in depth, including some that had long been in storage and rarely exhibited.

In addition to this research, there has been extensive conservation work on many pieces, either at the Met or in a local studio. This process has led to The Harlem Renaissance and Transatlantic Modernism shedding light on some lesser-known artists. For instance, Fisk, in addition to lending works by Winold Reiss and Aaron Douglas—who taught and painted murals at the university—is also lending Malvin Gray Johnson’s Harmony (1934). Depicting three performers playing stringed instruments, the bend of their knees in red trousers echoing the angular shape of a stage, it is one of several works portraying the music and nightlife that thrived in Harlem at the time.

“Malvin Gray Johnson, he died so young—he was 38—and that’s why he’s not as readily recognised as so many other figures of the Harlem Renaissance,” says Jamaal B. Sheats, Fisk’s associate provost of art and culture and the director and curator of the Fisk University Galleries. “So his work being featured in the exhibition is something I’m really excited about, because one thing that we do at Fisk is we’re always advocating for people to shift the gaze and to highlight other artists.”

While these HBCUs were where a number of Black artists from the 1920s to the 1940s worked and established art programmes that continue to teach new generations, in New York, exhibitions were being held at cultural centres such as the 135th Street branch of the New York Public Library, now part of the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture.

“Everything was right here, so it was like a ripe fruit growing,” says Tammi Lawson, the curator of the art and artefacts division at the Schomburg Center. “We have a 50-year jump on most places collecting Black art and Black culture.”

Lawson adds that the Schomburg Center has the largest collection of art by Augusta Savage in a public institution. Savage’s Gamin (1929), a bronze sculpture of a boy wearing a cap, is one of the works at the Met demonstrating how Black artists used portraiture at a time when stereotypes and frequently racist imagery dominated art and popular media.

“We wanted to have a survey of the different artistic approaches to portraiture, which I felt was a major medium for shaping this idea of the modern Black subject,” Murrell says. Key to this was broadening the perspective beyond New York and even the US. As emphasised by the second half of the exhibition title—Transatlantic Modernism—many Harlem Renaissance artists worked abroad in Paris, London and elsewhere and were involved in the international dialogue reshaping Modern art.

In her essay for the exhibition catalogue, Murrell observes that the writer and philosopher Alain Locke advocated for exhibiting art from what was then known as the “New Negro Movement” together with that of European Modernists. He wrote in his 1925 essay The Legacy of the Ancestral Arts: “Indeed there are many attested influences of African art in French and German Modernist art. They are to be found in the work of Matisse, Picasso, Derain, Modigliani and Utrillo among the French painters.” However, at the time, there were very few racially integrated museum exhibitions.

Murrell says that she “wanted to enact one of [Locke’s] aspirations” by bringing together European artists’ works with those made by African American artists during their time abroad. The Met show includes pieces by Matisse, Munch and Picasso—all of whom depicted Black subjects—as well as by artists such as the Jamaican-born sculptor Ronald Moody, who worked in London.

The wide range of influences and styles across the exhibited artists demonstrates how the reach of the Harlem Renaissance moved far beyond the narrow geographic focus of the term. But the Met proposes a collective narrative: of a movement that transformed modern visual expression through the portrayal of often everyday and ordinary moments in Black life. As Murrell says: “These are Black artists, photographers, painters, sculptors and filmmakers making work that represented the community—its individuals and the community as a whole—in the way that we chose to be seen.”

• The Harlem Renaissance and Transatlantic Modernism, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 25 February-28 July