Our Ecology: Toward a Planetary Living

Mori Art Museum, Tokyo, until 31 March 2024

The Mori Art Museum’s new exhibition Our Ecology: Toward a Planetary Living takes inspiration from the Indian historian Dipesh Chakrabarty’s idea of the “planetary” perspective needed to confront climate change. The show critically examines the ecological crisis through more than 100 works by 34 artists spanning 16 countries.

Emphasising interpersonal networks over objects, artists were invited to travel to Tokyo to “bring in ideas and realise works rather than shipping”, says Martin Germann, the exhibition’s co-curator. As a result, almost no art was shipped for the show and most of the gallery is occupied by 11 new site-responsive commissions. They include Kate Newby’s floor installation of objects collected from the streets of Tokyo, and Nina Canell’s participatory work inviting visitors to trample on seashells from Hokkaido that will later be repurposed in cement.

Looking at how artists respond to their surroundings is important, as “global problems started with local beginnings”, Germann says. That dynamic plays out in Martha Atienza’s video Fisherfolks Day 2022, addressing how a small fishing community in the Philippines is threatened by global tourism. Equal importance is given to art from the 1950s to the 1980s, including documentation of an early body of work by Hans Haacke, where he collaborated with animals, plants and meteorological conditions, and a reenactment of Yutaka Matsuzawa’s My Own Death (Paintings Existing Only in Time), first performed at the 1970 Tokyo Biennale.

The curators considered that “after forecasting and constant technological innovation couldn’t prevent today’s climate crisis, ‘back-casting’ seems important as well”, Germann says. The artists and seasoned eco-activists Agnes Denes and Cecilia Vicuña offer valuable references in this context, reminding us of their long-term commitment to the issue.

The show’s second “chapter” comprises a historical study guest-curated by the US-based scholar Bert Winther-Tamaki, examining how Japanese artists explored environmental issues under the country’s rapidly changing post-war social conditions and economic boom. Fujiko Nakaya’s 1972 video on the protests against the chemical company that caused severe mercury poisoning in Minamata, the Chernobyl series (1989-90) by the ceramicist Ryoji Koie, and Tetsumi Kudo’s Pollution–Cultivation–New Ecology series (1972-73), all address industrial pollution from the artists’ personal perspectives.

Intertwining various perspectives over its four chapters, the Mori exhibition presents “both smaller gestures of sensitivity and bold statements” with the view that, ultimately, “all art is ecological”, Germann asserts, quoting the philosopher and author Timothy Morton.

Maki Nishida

An image from Ishikawa’s Community Shaken by Construction of a Heliport series (2002). Much of her work has focused on the relationship between the people of Okinawa and the US military based there © the Artist, Courtesy of the artist and Tokyo Opera City Art Gallery

Mao Ishikawa: What Can I Do?

Tokyo Opera City Art Gallery, Tokyo, until 24 December

Japanese photography was, until recently, a male-dominated domain: male photographers, male publishers, male gallerists, male critics. The best-known names of Japanese photography are male and based in Tokyo: Nobuyoshi Araki, Daido Moriyama and Eikoh Hosoe. There are, however, female practitioners outside Japan’s capital who have created strong work for many decades. Mao Ishikawa, born in 1953 and based in her native Okinawa—the southernmost prefecture of Japan on the Ryukyu chain of islands—is one of them.

Ishikawa began photography in the 1970s, studying under Shomei Tomatsu at the Workshop Photography School in Tokyo. Returning to Okinawa, she photographed her colleagues while working in bars that catered to African American soldiers on the US military bases. Her pivotal series Red Flower: The Women of Okinawa (1975-77) and her photo book Hot Days in Camp Hansen!!, published in 1982, dynamically document the lives of the bar women and hostesses she befriended and their relationships with Black GIs. Images of Ishikawa herself, taken by her fellow Okinawan photographer Toyomitsu Higa, also feature in the book, embodying her immersive and diaristic approach.

A few years later, Ishikawa visited an American GI friend in Philadelphia to understand how he became a soldier stationed in Japan. The resulting series, Life in Philly (1986), balances street photography with close-up shots, high-spirited moments of happiness with the struggles of poverty. Ishikawa’s artistic practice has focused on people connected to Okinawa in and outside Japan, and often on historically marginalised communities. Her lens ranges from working-class women to interracial couples and mixed-race children, to priestesses and popular actors of traditional Okinawan theatre. She spends time with her photographic subjects and forms a relationship with them based on respect and trust, yielding powerful, intimate narratives.

Okinawa was placed under US control after the Second World War and only returned to Japan in 1972. The islands have been heavily influenced by the presence of US armed forces; more than 70% of US military bases in Japan remain in Okinawa today. Despite its beautiful nature, distinct ancient culture and the recent growth in tourism, Okinawa is still Japan’s poorest prefecture. Tensions persist between the Okinawan people, American soldiers and the Japanese government in Tokyo, which is seen as using the islands to house military bases unwanted elsewhere. In the history of post-war photography, Okinawa is mostly associated with Tomatsu’s 1960s and 70s work, which portrays the US presence in strong, symbolic and critical images. In contrast, Ishikawa’s position comes from within: it is more personal, tender and complex, often focusing on human commonality.

The Tokyo Opera City Art Gallery is now dedicating a major retrospective to the photography of Ishikawa, spanning her career chronologically from the 1970s to the present. The artist’s first solo museum exhibition in Tokyo introduces her photographic oeuvre to a wider public audience, up to recent works from The Great Ryukyu Photo Scroll series begun in 2014.

The show’s curator, Taro Amano, first encountered Ishikawa’s work 20 years ago. He included her in his group exhibition Non-sect Radical: Contemporary Photography III at the Yokohama Museum of Art in 2004, together with other international photographers who were socio-politically engaged without having a specific political affiliation. Since then, Ishikawa’s photography has appeared throughout the world. In 2017 her first English-language monograph was published by Session Press.

“The works in this exhibition do not have a direct political message, but rather feature various contexts,” Amano explains. “It is up to the individual viewer which context they focus on.” He emphasises the strength of Ishikawa’s body of work even beyond its socio-critical and political concerns: “Persistently looking at a range of people, her gaze has the power to see the core of human existence.”

Ishikawa’s works offer fresh, honest and personal perspectives on Okinawa in which humanity shines through. The question posed by the exhibition’s title, What Can I Do?, was chosen by the artist. Her hope, Amano says, is to encourage people to think about “what they can do for society, no matter how trivial this might seem”.

Lena Fritsch

Box (2003-19) by Nobuya Hitsuda, whose experimental approach has inspired many younger artists Photo: Kei Okano; © the artist, courtesy of the artist and Kayokoyuki

Nobuya Hitsuda

Kayokoyuki, Tokyo, until 3 December

Following a 2019 solo exhibition of Nobuya Hitsuda, blame not on reasons, Kayokoyuki gallery has teamed up with the painter Hiroshi Sugito for a presentation contextualising the work of the contemporary master affectionately known as “Hitsuda-sensei” (teacher).

Born in Tokyo in 1941, Hitsuda had an influence on contemporary Japanese art that cannot be overstated. Having taught at the Aichi Prefectural University of the Arts and Tokyo University of the Arts, he is a rare academic whose artistic practice is on par with his ability to impart knowledge. Hitsuda’s painting achieves its lightness through playful bricolage. It embodies a space in which memory and imagination interact, evoking the subjective experience of the flow of everyday life.

It is no wonder that his students have pursued a broad range of approaches in their own practices, from his fellow painters Sugito, Yoshitomo Nara and Kyoko Murase to the conceptualist Yuki Okumura and the mixed-media artist Emi Otaguro. The experimental imperative in Hitsuda’s work is evident. A case in point is a mood board-like installation in his 2019 exhibition. Taped to the wall were reproductions of Hitsuda’s paintings, Polaroids of the works and the empty cityscapes that inspired him, and patterned and painted paper scraps from his studio; this ensemble was disrupted by the inclusion of a finished and framed work on paper.

In 2009 the Aichi Prefectural Museum of Art and the Nagoya City Art Museum mounted a tribute show, placing Hitsuda’s art alongside work by his students. Kayokoyuki’s new solo show will offer insight into the work of Hitsuda, while at other exhibitions around the city visitors can see for themselves the extent of his influence on a younger generation.

Jeffrey Ian Rosen

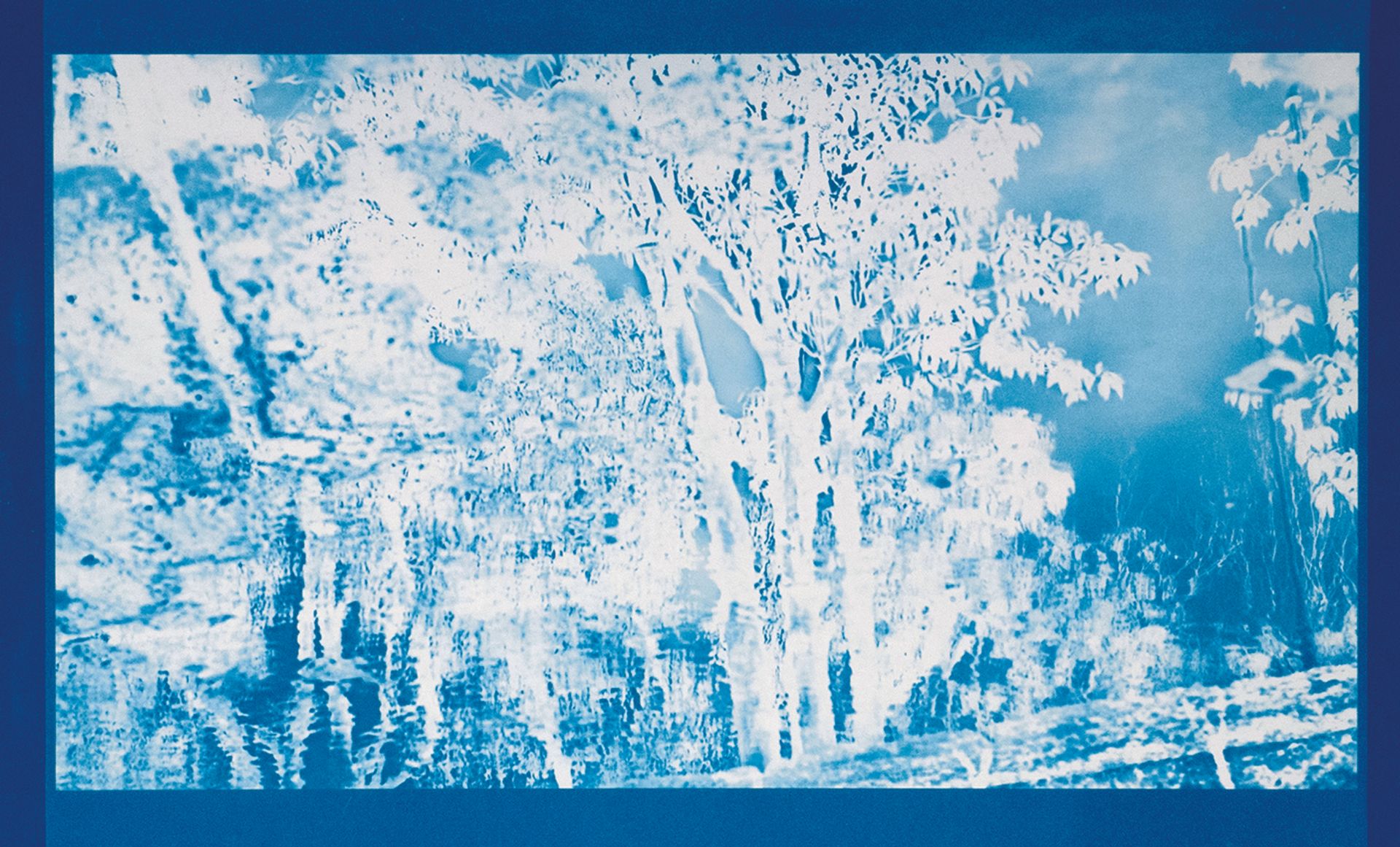

Miyake has begun producing videos from her cyanotypes, such as this still from Nowhere in Blue (2023) © The artist; courtesy of the artist and Waitingroom

Saori Miyake: Nowhere in Blue

Waitingroom, Tokyo, until 19 November

For Saori Miyake, shadows are an essential part of depiction. Her works only make marks by passing through a negative state. In Blue Print (2023), for instance, one of Miyake’s recent cyanotypes, the forms of a tree, its branches and individual leaves are all distinctly visible. But they only appear through their pictorial absence, as voids on the paper where no pigment appears.

Although the Kyoto-based artist trained as a painter, she has moved from oil on canvas to photographic processes precisely because of her interest in shadows and the pictorial possibilities within them. “While a shadow is an optical phenomenon,” Miyake says, “it is also an extremely powerful metaphor”. Her previous work has used tracings of found images—including photographs taken by a Japanese athlete who visited Berlin for the 1936 Olympics—to make photograms, sending them through negative and positive.

Miyake’s solo show at Waitingroom gallery in Tokyo will include cyanotypes, a camera-less process in which light-sensitive paper is partially covered with an object or a screen; the areas exposed to sunlight turn a rich blue colour. This is one of the earliest forms of photography, and Miyake notes the influence of the pioneering 19th-century English botanist Anna Atkins, who made cyanotypes of her specimens.

Blue Print departs from Atkins’s botanical enquiries to explore concepts of landscape, a genre that has interested Miyake since the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic. Drawing on her own experiences of walking through nature, Miyake is interested in the gap between the realism implied in the English term “landscape painting” and the spiritual implications of landscape in East Asian painting traditions.

Such tension between scientific and artistic qualities resonates with Miyake’s core idea of the “painterly image”, which can emerge from a wide range of visual material beyond conventional painting, including images that circulate online. “I am moved,” Miyake says, “by the feeling that anyone who sees images on social media takes on certain qualities of a painter”.

Dan Abbe

• Waitingroom, 2-14-2 Suido, Bunkyo-ku, until 19 November

A 2022 paper-and-plaster work from Terauchi’s One is Many Many is One series Photo: Fabian Stransky

Yoko Terauchi

Hagiwara Projects, Tokyo, 1 November-2 December

Yoko Terauchi started her career in the late 1970s, making welded steel sculptures and studying at St Martin’s School of Art in London with Anthony Caro. But she soon had questions and doubts as she observed “everyone making Caro-esque sculptures and the tutors making categorical assertions on what was good and bad”, she recalls.

Sceptical of these judgements, and the tendency towards dualism in Western thought, she shifted her sculptural practice from the creation of objects to a means of conveying her view of the world, which she describes as “one as whole”. Terauchi set out to visualise how humans only impose binary oppositions on the world by force of cognitive habit. Her works made with paper and telephone cables dissolved the concepts of front/back and inside/outside, challenging the validity of such distinctions. Her career flourished after her participation in the seminal 1983 exhibition The Sculpture Show at the Hayward Gallery and Serpentine Gallery in London. By the end of the decade, Terauchi had moved on to making installations that physically immerse the audience in metaphysical concerns, frustrating any easy materialistic interpretation.

Terauchi feels that we tend to believe what we see as true even though our perception is limited and subjective, everyone only grasping a different part of a thing, leading to inevitable conflicts. With her belief in the wholeness of humanity and the universe, since the 1980s she has addressed the meaninglessness of division by enquiring into concepts such as dualism, relativism and empiricism. She is at present exploring the “one” proposition of Zen philosophy, which accepts any existence as being “one” and an embodiment of “all” at the same time.

In her latest solo exhibition at Hagiwara Projects gallery, Terauchi presents a new site-specific installation from the series One is Many Many is One (2022). This is the latest development of ONE, an ongoing series since 2004. An artist statement from 2022 reads: “when we count something as ‘ONE’/this is the beginning of dividing the world/which in fact is One as Whole… why can’t we accept the world as it is?”

Inviting the audience to stand in the middle of this question, a set of seemingly unrelated objects—a stretched-out sheet of paper with countless holes and a plaster cast—waits for them in the space. M.N.

• Art Week Tokyo runs 2-5 November. See all of our coverage here