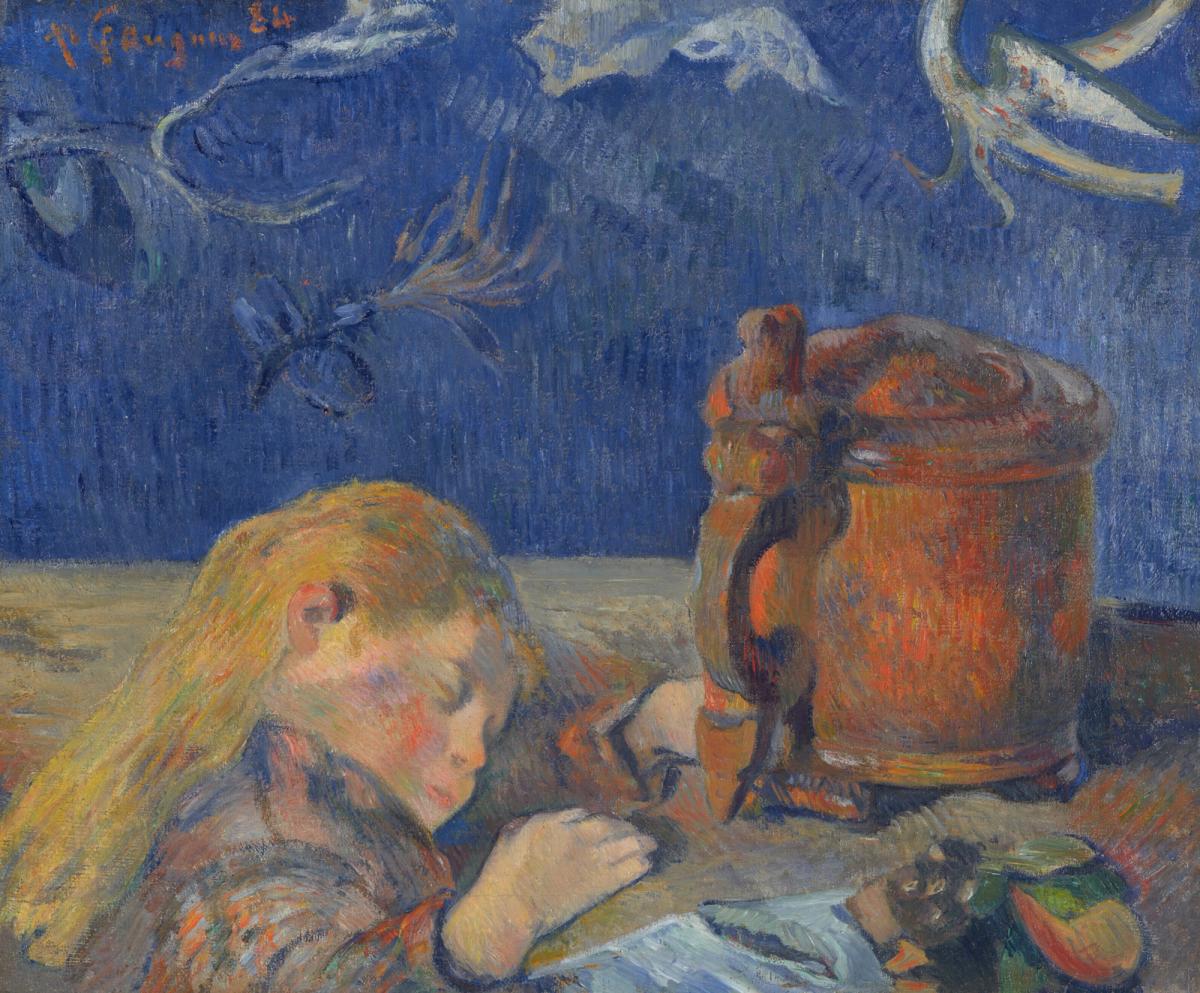

Paul Gauguin’s, Clovis Endormi (1884)

Masterpieces from the Collection of Sam Josefowitz, Christie’s, London, 13 October

Estimate: £3,000,000-£5,000,000

The provenance of this oil painting by Gauguin lists the artist’s brother-in-law, Hermann Thaulow, and his sister-in-law, Pauline Elizabeth Thaulow, both based in Tromso, Norway, as former owners. It depicts Clovis Gauguin, the artist’s son with Mette-Sophie Gad, who Christie’s describes in an essay as “his favourite child”. One of dozens of works by the painter to depict the interior lives of children, it shows Clovis asleep beside a doll and a large tankard. It was painted during a turbulent time for Gauguin’s marriage, as Mette-Sophie had returned to her native Denmark that year, taking two of their children with her but leaving Clovis behind.

The last time this painting was offered on the open market was in 1984, by Richard L. Feigen gallery in New York, where it was bought by the prominent collector and music entrepreneur Sam Josefowitz. His collection, which spans some two millennia of art, is being offered in a series of sales in London and Paris, kicking off during Frieze Week, and culminating during the Paris+ par Art Basel fair. Clovis Endormi has been on loan to the Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto since 2008. There is no stipulation that the buyer must loan it to the museum.

Courtesy of Christie’s

Roman Sardonyx cameo portrait of the Emperor Claudius (around AD41-54)

Rothschild Masterpieces, Christie’s, New York, 11 October

Estimate: $200,000-$300,000

This first-century imperial cameo coming up to the block at Christie’s New York may be small, but it is of major historical significance. A portrait of Emperor Claudius, it is thought to have been mounted in Renaissance Germany. The cameo has been consigned from the collection of the French branch of the Rothschild banking dynasty. It appeared in the renowned Marlborough Gems auction in 1899 at Christie’s London, where it sold for £3,750, making it the most valuable object in the sale.

Shortly afterwards, it entered the Rothschild family collection. The cameo was seized from the Rothschilds after the Nazi occupation of Paris in 1940 by the Reichsleiter Rosenberg Taskforce, a group dedicated to confiscating cultural property, and stashed in the Altaussee salt mines in Austria. It was later recovered by members of the Monuments, Fine Arts, and Archives programme of the Allied armies, better known as the Monuments Men, and returned to France and the Rothschild family in 1946, according to Christie’s. “You’ve got this thing which has got extraordinary history in it and it just fits in the palm of your hand,” says Jonathan Rendell, the deputy chairman of Christie’s Americas. “That to me is staggering, and it’s very rare to see.”

Courtesy of Bonhams

Gilt copper alloy figure of Manjushri, 15th century

The Claude de Marteau Collection part IV, Bonhams, Hong Kong, 6 October

Estimate: £590,000-£780,000

This 600-year-old gilt bronze portrays a seated Arapachana Manjushri, representing the bodhisattva (a Buddhist figure somewhat comparable to a Christian saint) of perfected wisdom. Given to a Tibetan monastery by a Chinese court as a diplomatic gift, it is emblematic of an unusually heightened period of cultural exchange between the two regions that took place in the early 15th century.

It comes from the Belgian antiques dealer and collector of Buddhist and Hindu sculptures Claude de Marteau, having come into his possession between the 1960s and 1970s, according to Bonhams specialist Edward Wilkinson. The exact details of how and when De Marteau acquired the sculpture are not known, as he was “not a great record keeper”, Wilkinson says. While acknowledging that the provenance of works from other Himalayan countries, notably Nepal and India, are now under intense scrutiny amid mounting evidence of illict dealing, he says this dilemma is less applicable to art from Tibet.

“Most was smuggled out of the country by Tibetans themselves during the Cultural Revolution—the Chinese destroyed around 80% of Tibetan monasteries during this period, presenting something of a paradox: should the art have stayed there and risked being lost?” Wilkinson adds that Bonhams has “worked with renowned collectors in the field and performed due diligence” to give itself certainty that the work entered De Marteau’s collection by legitimate means.

Courtesy of Sotheby’s

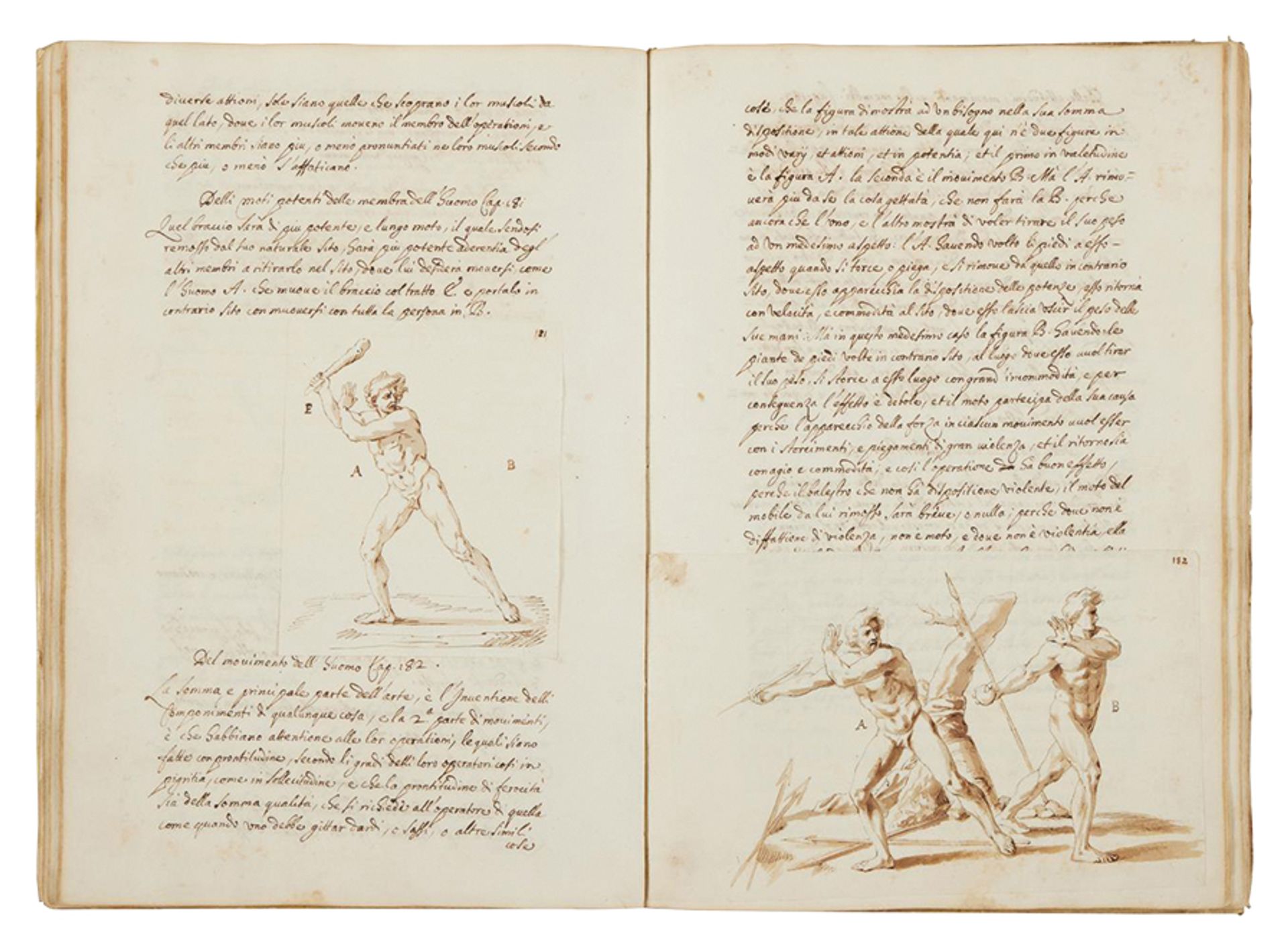

Abridged manuscript of Leonardo da Vinci’s A Treatise on Painting (1638-41)

Bibliotheca Brookeriana: a Renaissance Library. Magnificent Books and Bindings, Sotheby’s New York, 11 October

Estimate: $250,000-$300,000

An early manuscript of Leonardo’s A Treatise on Painting leads a sale of books and bindings from the collection of T. Kimball Brooker, expected to fetch $25m in total. Offered this month in New York, it marks the first dedicated evening sale for books and manuscripts at Sotheby’s in more than a decade. Leonardo’s treatise is well known as one of the first, and most succinct, texts to argue that painting could be treated as a science. It contains anatomical diagrams, as well as guidelines for depicting the natural world, such as his famous “branching rule”, which states that “all the branches of a tree at every stage of its height when put together are equal in thickness to the trunk [below them]”.

Following his death in 1519, Leonardo’s loose manuscripts were gathered by his pupil and heir Francesco Melzi, who copied them, with their corresponding drawings, in a codex now owned by the Vatican Library. This abridged version offered by Sotheby’s contains all the original 375 chapters and 56 illustrations in ink. It was made between 1638 and 1641 in the atelier of Cassiano dal Pozzo; its “potentially heretical passages” have been removed, according to Sotheby’s.