When the heavy crown of England pressed down upon her on that Coronation Day in 1953, Elizabeth Windsor was transfigured into a dynastic icon. As with her Elizabethan namesake, a sphinx-like inscrutability cloaked her ever after. We discovered no more of her private taste or aesthetic preferences than the horses and headscarves and Balmoral heather, electric bar heaters and crimson carpets spotted in photographs and television appearances.

The superlative Royal Collection of paintings sculptures and palaces, formed the backdrop and fabric of her daily life. Most of the more than 5,550 acquisitions made during her reign and listed in the trust’s archives comprise the random gifts and presentations of foreign and British dignitaries: a basket from Tonga in 1954, a jar of grain from Canada. The Queen was reported to have said that, while the Prince of Wales deplores their quantity and quality, “I’ve got no taste so I’m delighted with them.” But her own purchases remained almost completely uncharted territory.

'If everything you’ve heard is true, you’d think the high point of her artistic desire should be Stubbs, but perhaps it’s Sir Alfred Munnings?' speculated the style commentator Peter York

“If everything you’ve heard is true, you’d think the high point of her artistic desire should be Stubbs, but perhaps it’s Sir Alfred Munnings?” speculated the style commentator Peter York. Her beloved royal servant “Crawfie” (Marion Crawford) tells us that Princess Elizabeth played horses obsessively and racing, breeding and riding preoccupied her ever since. So New Zealand, America and Canada all presented her with small equestrian bronzes. Slovenia did so, too, pairing its gift with a live Lipizzaner stallion in 2008. Munnings contrived miniatures for the dining room of Queen Mary’s Dolls’ House in the Thirties, and two of her magnificent Stubbs form a backdrop to a rather nice oil painting of the Queen breakfasting at Windsor painted by Prince Philip in 1965. But her own purchase that year—discovered by Arnold Machin after she casually asked his opinion of the artist during a portrait sitting for the Royal Mint—was a Lowry, almost the only clue that we have to her collecting.

A cane basket given by the then Queen of Tonga to Queen Elizabeth in 1954 Royal Collection Trust / © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2022

Houses arrived ready-made with her job, the first a Wendy house-sized, two-storey cottage when she was six, a gift of the people of Wales. The throne meant a life divided between Buckingham Palace and the slightly more private Windsor Castle (she had hoped to live in Clarence House with the palace as her office). Chatsworth was like being at home—she complimented her hostess during a visit—but far more comfortable.

But on most matters of taste, she delegated. Just as the Prince Consort had done a century before, Philip took agency over their accommodation, beginning with the floating palace that was to be the royal yacht Britannia. The royal couple recruited the architect and designer Hugh Casson, the impresario behind the Festival of Britain, with the modernising—if not Modernist—agenda of reworking its formal, Edwardian designs for something progressive, relaxed and contemporary, their “home from home”.

Away from her palaces of state, the Norfolk mansion of Sandringham and Balmoral Castle in Scotland may have represented her unpretentious ideal, with brown furniture, Edwardian field sports and a full complement of servants

“The Queen is a meticulous observer with very definite views on everything from the door handles to the shape of the lampshades,” Casson noted. He became their interior decorator of choice, ushering in a lighter, classic country-house style at Buckingham Palace, Windsor and Sandringham that included a guest suite in the Edward III Tower at Windsor showcasing works by contemporary British designers such as the ceramicist Lucie Rie. But while the Queen was officially final arbiter of taste here, everything had been pre-selected by Philip and Anthony Blunt, Surveyor of the Queen’s Pictures, while the 1992-97 post-fire restoration of Windsor was directed by a committee which Philip also chaired.

Away from her palaces of state, the Norfolk mansion of Sandringham and Balmoral Castle in Aberdeenshire, where she died, may have represented her unpretentious ideal, with brown furniture, Edwardian field sports and a full complement of servants. At Balmoral a nervous Windsor clergyman remembers luncheon of macaroni cheese and mince, and when Machin took her portrait there he saw her knitting after supper surrounded by her friends and Scottish cousins. A silver box of dog biscuits sat in front of her dinner plate; at royal picnics the lady-in-waiting Anne Glenconner watched her making the salad and washing up.

A trayful of tiaras

Instead the Queen exercised her royal prerogative in fields where she was most expert: regalia and portraiture. Princess Margaret’s marriage to Antony Armstrong-Jones, Earl of Snowdon, provided her with a superb image-maker and taker of photographs, modern-medieval pageantry (Prince Charles’s investiture at Caernarvon Castle) and industrial design.

She understood jewels, crowns and how to style them. Machin remembered her trying on a trayful of tiaras before his portrait sitting and she complained to Noël Coward that the too-large investiture crown commissioned by Garter King of Arms looked like a candle snuffer on Charles’s head. Cecil Beaton had been her mother’s photographer of choice, but the Queen recognised Tony Snowdon’s brilliance, retaining his services from the 1950s until long after his divorce.

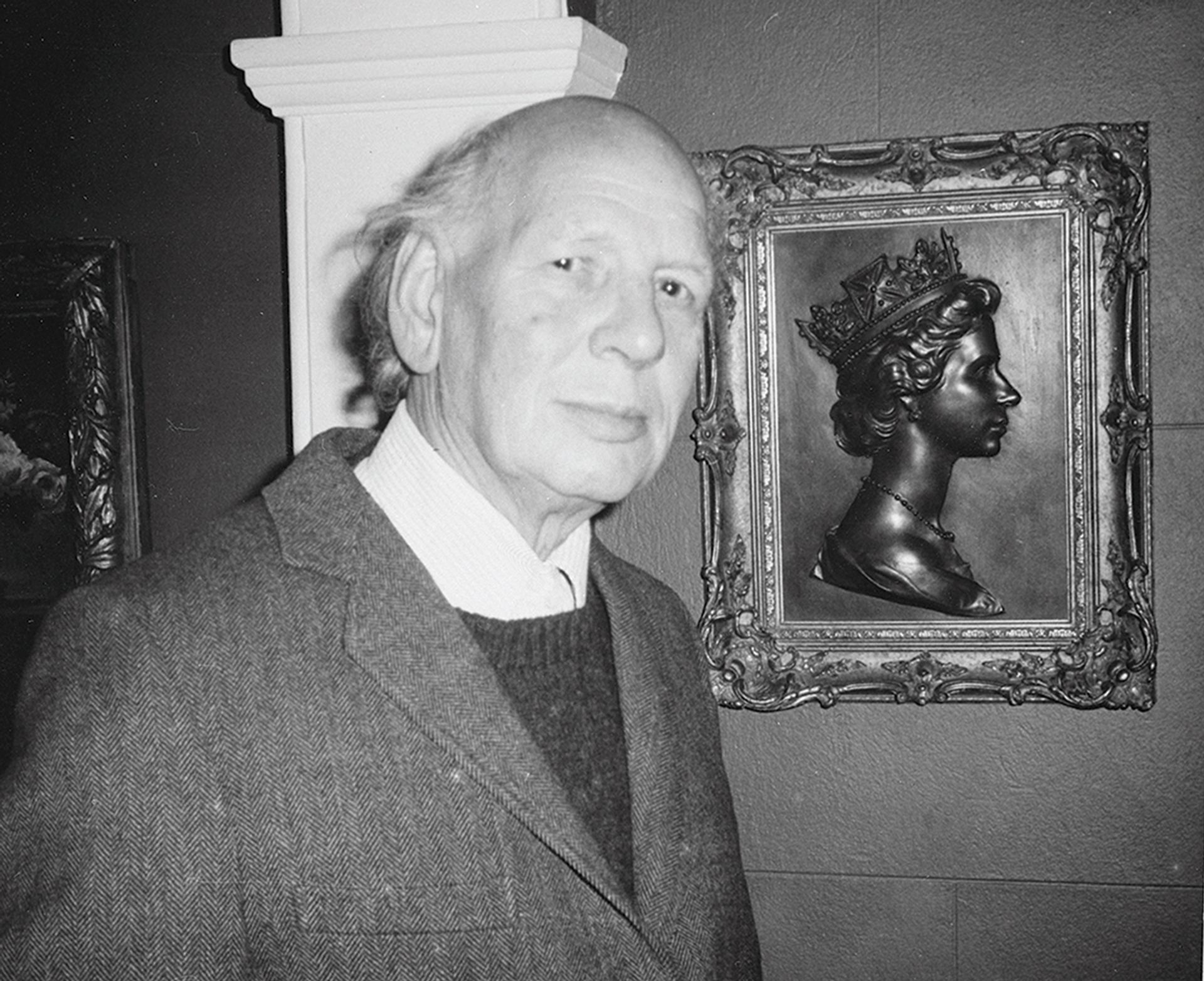

Arnold Machin with the relief portrait he made of the Queen—which is known to have pleased her—for the Royal Mint Supplied by The Royal Mint Museum

Machin’s relief portrait for the Royal Mint and its subsequent adaptation for her likeness on postage stamps pleased her, too, as did his sinuous 1970s cameo of Prince Charles and other royal portraits for Wedgwood. But stamps, with their miniaturised heraldry amounting to a royal logo, have been important since her philatelist grandfather George V’s time. When Tony Benn was her Postmaster General, she refused the attempt of the artist and illustrator David Gentleman to remove her head entirely from their design. When Gentleman simplified her likeness to the Machin profile, Benn spread his designs on the Buckingham Palace carpet for her approval. These are the icon-images she chose and minded about, rather than those created by Lucian Freud, Rolf Harris or Chris Levine.

She complained to Noël Coward that the too-large investiture crown commissioned by Garter King of Arms looked like a candle snuffer on Charles’s head

Beyond this, those who know will not or cannot tell—John Betjeman, Hugh Casson, the Queen Mother, Princess Margaret, all dead, the keepers of her works of art and intimates-in-waiting maintaining her secrets. Freighted and weighted with the ghost-ridden, pompous furniture and apparatus of her queenliness, her Leonardo drawings, Holbeins and Van Dycks, she nevertheless seemed a creature incarnate with perfect commonsense, both excused and “above” taste. We knew her as we were allowed to know her, on television and the coins in our pockets, or fell for the brilliant fantasy figure of Alan Bennett’s dramatic tribute, A Question of Attribution, the Queen who only exposed her discreet connoisseurship before Blunt, her surveyor of pictures.