The sprawling Documenta 15 exhibition, which opened in Kassel over the weekend (until 25 September), was never going to play by the rules. Since its inception in the wake of the Second World War, controversy and chaos have accompanied the German quinquennial, which increasingly attracts not only attention from curators and artists but the scrutiny of politicians too—and this year was no different.

From a karaoke session at the opening press conference to entire sections of the exhibition devoted to sleep and informal play, the show, organised by the Indonesian art collective ruangrupa, wholeheartedly challenged the idea of what a large-scale exhibition could look like, for better and for worse. Indeed, this edition was perhaps the most visually unappealing, but politically charged to date, delivering a show in which questions of ethics eclipse those of aesthetics and the lines separating art and social practice have all but disintegrated. What is left is a series of artistic responses to the philosophy of lumbung (Indonesian for rice barn), which advocates for resource sharing, material equity and communal good. Within this were plenty of eyebrow-raising moments. Here are some of the most notable things we saw.

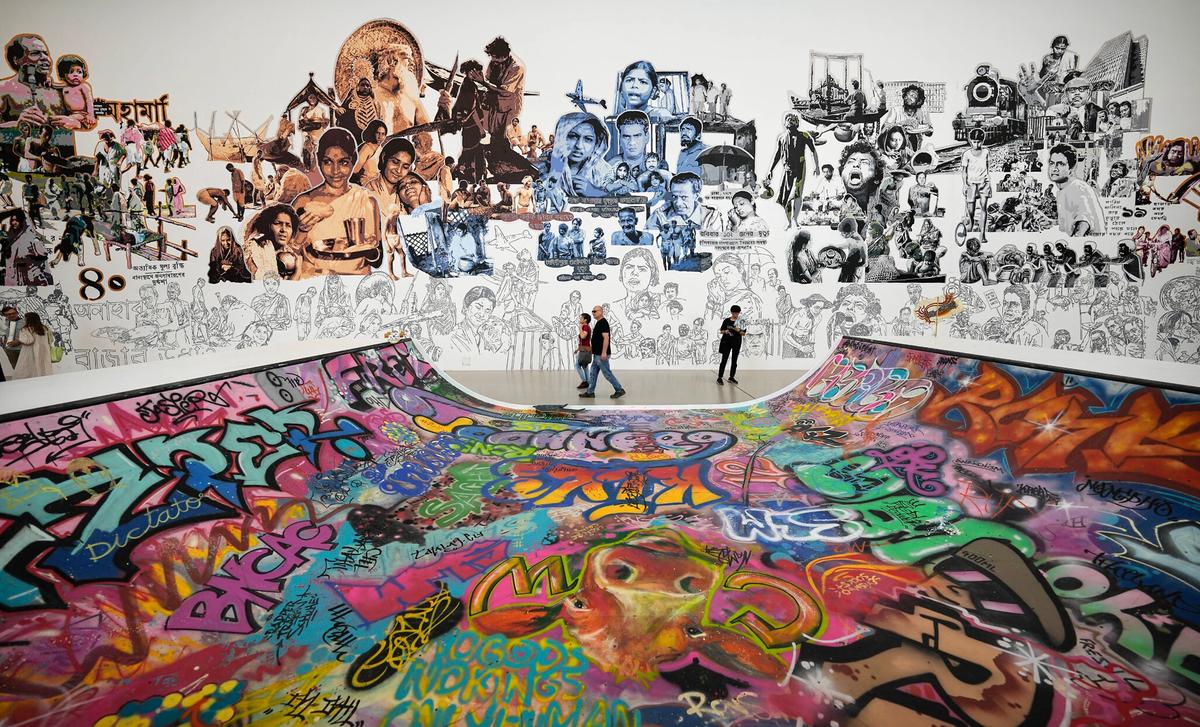

Detail from Taring Padi's People’s Justice (2002) © The Art Newspaper

Artists censor work as antisemitism row endures

Accusations of anti-semitism have plagued Documenta 15 since January, due to the anti-Zionist stance of a number of exhibiting artists. This was, unsurprisingly, a central subject of conversation during the opening, which featured a visit from Germany's president, Frank-Walter Steinmeier. In a speech that read as a warning to the exhibition's organisers, he said that Documenta must "do more" to address and rectify the issue.

This demand was put to the test on Sunday (19 June), when a 2002 work in an installation by the Indonesian collective Taring Padi was removed from the show by the artists due to its perceived antisemitic content. The offending work, part of a larger cardboard banner, depicted "a caricature of a Jew with sidelocks, a cigar, and SS symbols on his hat," according to German art publication Monopol.

Taring Padi said in a statement that they are "saddened that details in this banner are understood differently from its original purpose" and "apologise for the hurt caused in this context".

A demonstration in solidarity with ruangrupa and The Question of Funding that took place in Kassel on 18 June © The Art Newspaper

Pro-Palestine demonstrations

Accompanying the antisemitism row have been a number of racist attacks against pro-Palestine artist groups, which led to increased security and police presence throughout the show. Perhaps because of this, no large-scale protests took place, as was expected.

The only demonstration of the weekend was held on Saturday, opposite the Friedrichsplatz, in support of Palestinian rights. It was led both by the Palestine artist group The Question of Funding as well as the Kassel faction of the German-Palestine Society (DPG), a local anti-Zionist group that terms Israel as "an apartheid state". Here, demands for Israel to pay reparations to Palestine were made, along with chants that declared: "From the river to the sea, Palestine will be free."

Overworked employees cast doubt over "lumbung spirit"

A number of Documenta staff told The Art Newspaper that this edition is the most intense they have staged, and with good reason: 1,500 artists (and counting) have been invited to show work, requiring lots of extra red tape, from last-minute visas to readjusted wall labels.

In the words of the Venice Biennale curator Cecilia Allemani, organising a biennial is "80% logistics", which is something that artists might not consider when inviting all their friends to the party (one collective brought around 100 other artists to Kassel to show work). "I question where the lumbung spirit ends—it certainly doesn't seem to extend to the artistic team whose hours have increased dramatically, often staying up till 3am or 4am with no extra pay," said one curator who wishes to remain anonymous.

Mini-Berghain comes to Kassel (and with pointed politics)

In true Documenta style, the opening weekend's best parties also functioned as gesamtkunstwerk thanks to the Delhi collective Party Office, which is throwing a series of BDSM-friendly music events in a basement nightclub throughout the show's 100 days. This is not merely an opportuntity for illict revelry, but also a space to practise the philosophy of "care, resilience and community building" that is the raison-d'être of Party Office.

Three back-to-back nights brought acclaimed DJs such as Juliana Huxtable and Slim Soledad into a club at the WH22 venue, which featured a dancefloor, bar, swings, a soft-leather room with paddles and a number of darkened corners for intimate tête-à-têtes. Before descending into the fun, all participants were required to read and agree to a list of rules that stressed the importance of consent and mutual care in nightlife environments.

But the club's entry policy—which privileges non-white, queer and neurodivergent people—was also deemed exclusionary by a number of hopeful partygoers, mainly white men, who were rejected at the door by Party Office hosts. "You are doing the wrong thing, you are misguided!" shouted one man as he was denied entry. Unfazed, Party Office's founder Fadescha reminded the crowds that they are creating a space for people that might not feel comfortable in traditional club environments—and if anyone takes an issue with this policy, they are free to go elsewhere.

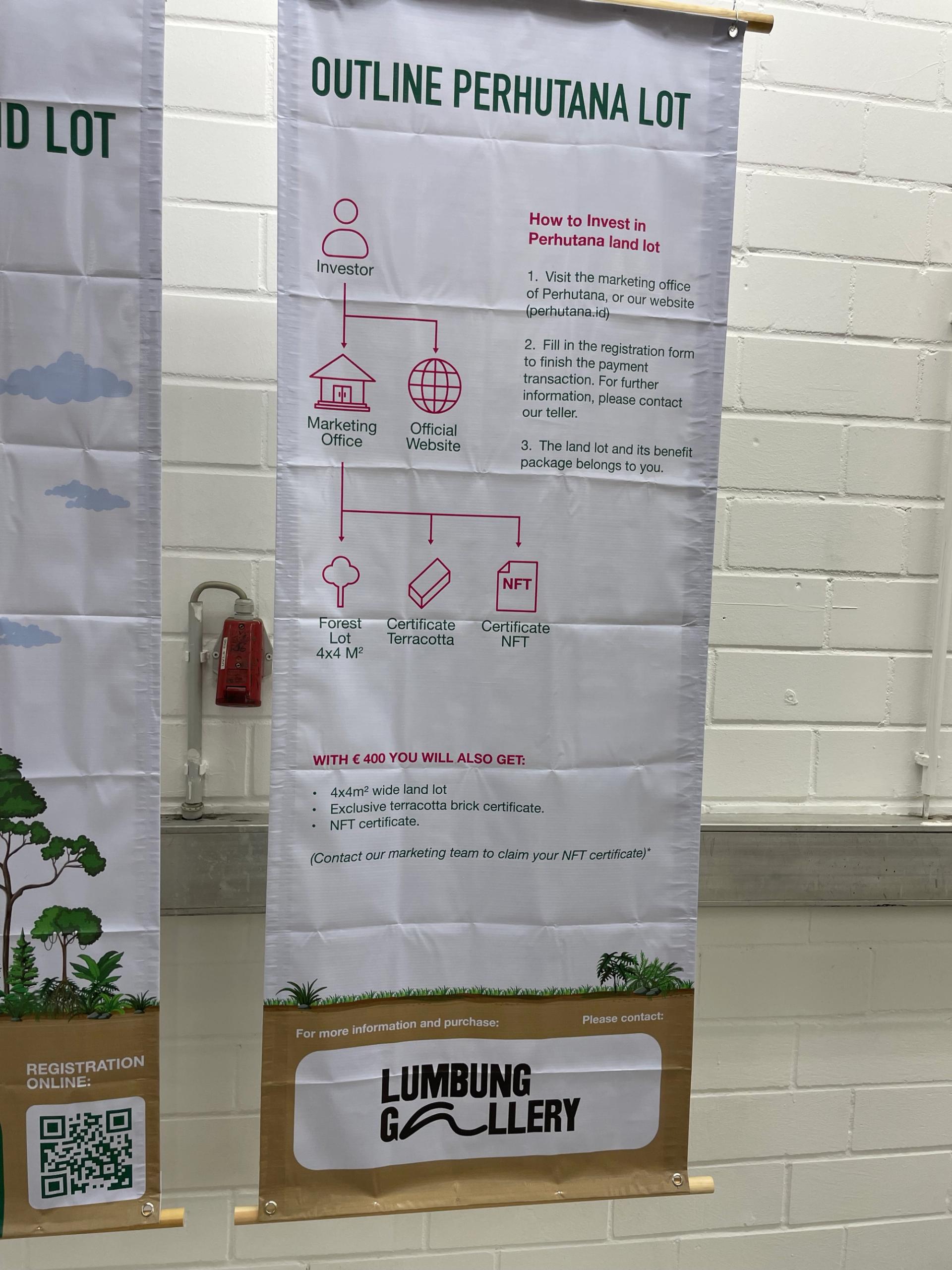

Jatiwangi Art Factory invite you to buy a plot of forest to protect it from industrialisation—and it comes with an NFT © The Art Newspaper

Saving and destroying the planet

In the vast Hübner Areal venue of Kassel's industrial east, the Indonesian collective Jatiwangi Art Factory's large exhibition displaying their practice of creating clay tiles is accompanied by a confusing message about the enviroment. The collective, which are based in the Northern Majalengka area of Java, are attempting to protect swathes of rainforest that are under threat from industralisation and human expansion.

To counteract this, they are offering 16m sq. plots of the forest for sale, each of which will be considered "sacred" and protected by Indonesian law. However, the plot comes not only with a title deed, but a corresponding NFT too. The recent controversy around the environmental impact of cryptocurrency and other blockchain-based assets makes one question whether the best way to protect the planet is by emitting more carbon into the atmosphere.

An anti-exhibition for those "haunted by biennials"

It was no secret that this year's Documenta would treat the concept of an exhibition as something to be deconstructed—and resolutely fulfilling this promise was the collective Le18, from Marrakech, who staged a sort of "anti-exhibition" in protest against the biennial model. Plans were scrapped in April for a more conventional show, as the group butted heads with the Documenta organisers, one of its members, Nadir Bouhmouch says. Instead, the group have turned their space into a library and cinema with places to rest for free—something that is a "vital resource for a large show", Bouhmouch adds. In lieue of an exhibition, there will be a series of talks held throughout Documenta that will ask questions such as "what does it mean to be together?". Still, according to Le18, people entered the space on the opening weekend expecting to see art objects and were confused by the unconventional nature of what they found. "They are haunted by the spectre of the biennial."