In their new and bold visual style, Venetian School artists discarded Florence’s obsession with form in favour of rich colours, greater dynamism and unparalleled sumptuousness. Works by Bellini, Giorgione, Tintoretto, Titian and Veronese are intrinsic products of the city: they seem to course with the hedonism, commercial energy and grandeur of the Renaissance republic. Today, the paintings and frescoes line the walls of busy museums and quiet churches tucked away along thoroughfares throbbing with tourists. Other spaces in the city display important collections of Modern art. Whether you are visiting for the Biennale or simply for a weekend break, our list will guide you through Venice's vast and diverse artistic heritage.

Bellini's San Zaccaria altarpiece (1505), church of San Zaccaria

Bellini_San Zaccaria_ Credits Web Gallery of Art

Placed above the altar on a wall packed with baroque paintings, Bellini’s sumptuous masterpiece immediately grabs your attention. In this “sacra conversione”—a genre in which Madonna and child are presented alongside assorted saints from various eras—the artist exhibits his adherence to Giorgione’s rich, moody colours, with lavish blue and yellow robes for Peter and glorious red for Jerome. The 74-year-old Bellini painted the scene in a niche framed by flanking columns. By ingeniously integrating the actual columns into a perfectly depicted chapel in the painting, he makes the work feel as though it is opening up from the architecture itself.

Tintoretto’s Crucifixion (1565) at the Scuola Grande di San Rocco

Tintoretto’s Crucifixion (1565)

The charitable San Rocco confraternity, a wealthy group of Venetian citizens, constructed the Scuola Grande as their seat.Tintoretto adorned the gilded interior with 60 works depicting scenes from the Old and New testaments over a period of two decades. The result is a breathtakingly abundant offering that stands as Venice’s biggest pictorial cycle. You are unlikely to miss the awesome Crucifixion, arguably Tintoretto’s finest work. The huge canvas teems with despairing throngs, gathered at the foot of the cross to the backdrop of a thundering sky.

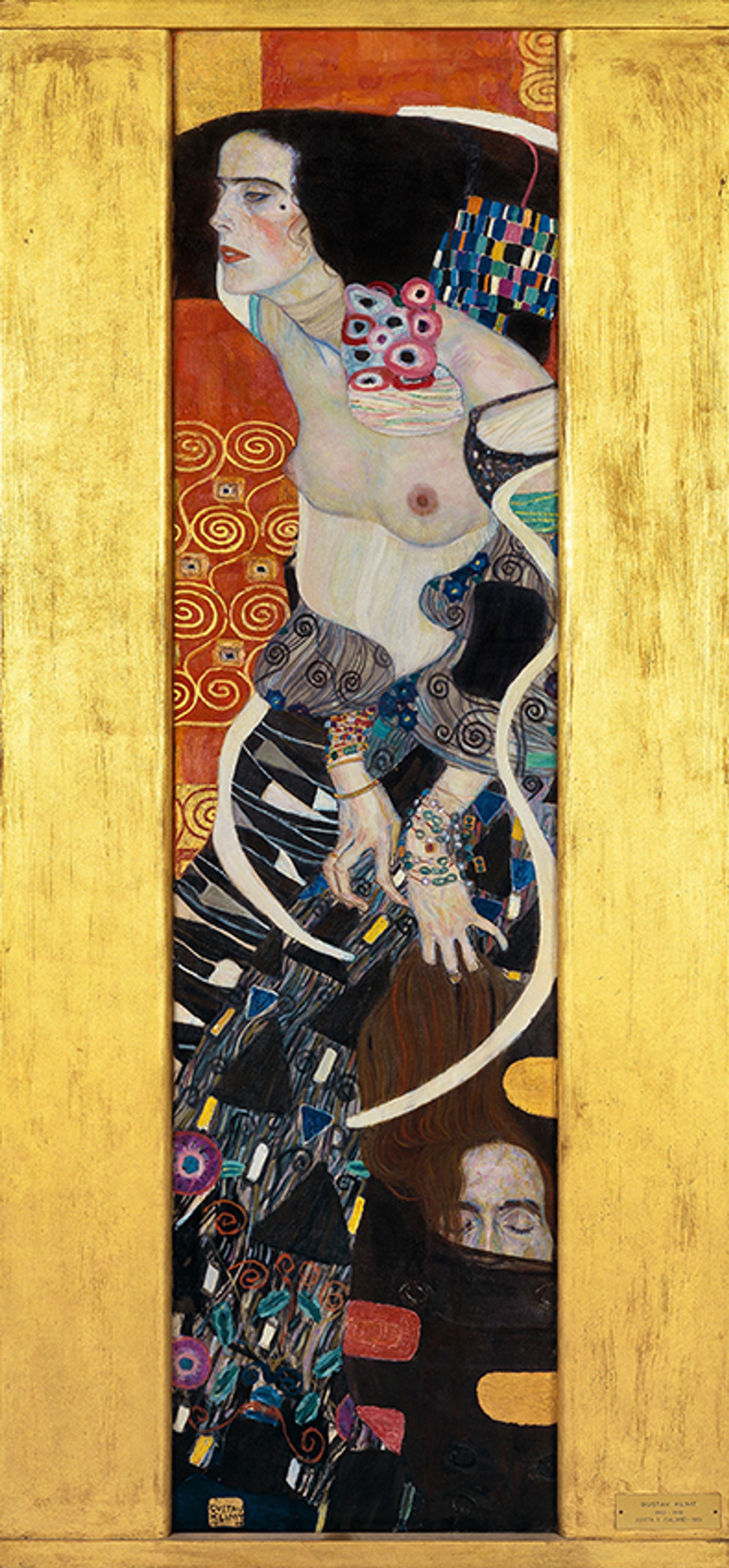

Gustav Klimt’s Judith II (1909), International Gallery of Modern Art, Palazzo Ca’ Pesaro

Gustav Klimt, Judith II (1909)

According to the bible, Judith decapitated General Holofernes to save her city, Bethulia, from destruction. Klimt first depicted the figure in 1901, returning to the subject eight years later in this riot of contrasting colours. Imbued with a sense of dynamism reminiscent of Salome’s Dance of the Seven Veils, the work was acquired by the city of Venice after the 1910 Biennale. It now hangs in the Gallery of Modern Art on the first two floors of Ca’ Pesaro, once home to the powerful local family that produced a 17th-century Doge. The third floor of the palace hosts the Museum of Oriental Art.

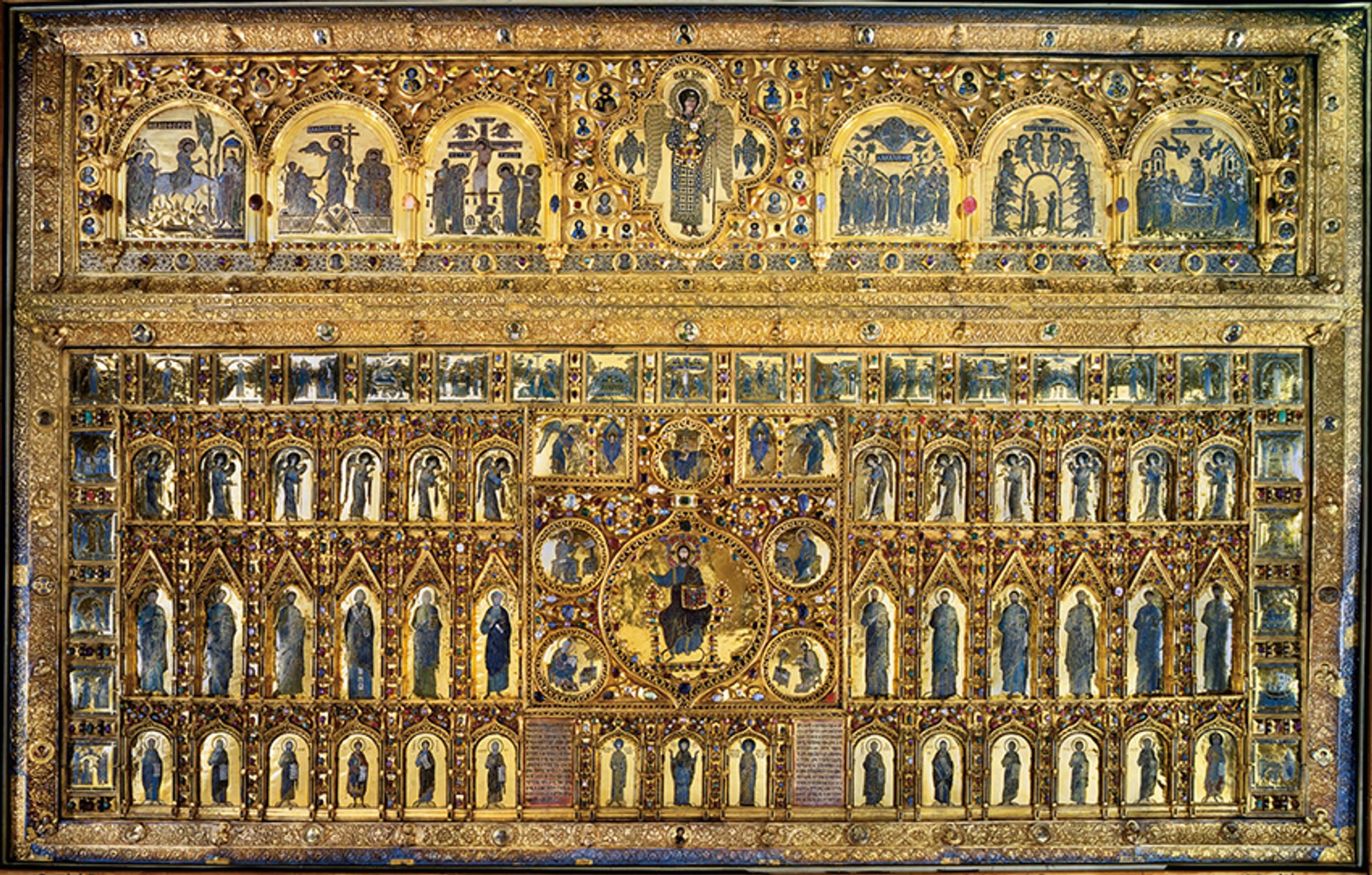

Pala d’Oro (10th-13th century), Saint Mark’s Basilica

Pala d'Oro, Saint Mark's Basilica, Venice

Nicknamed the “Chiesa d’Oro” (“Church of Gold”), Saint Mark’s Basilica is one of the world's finest examples of Italo-Byzantine architecture. Its 8,000 sq. m expanse of dazzling mosaics—created by the likes of Veronese, Tintoretto and Titian, and sometimes by using 24-carat gold leaf—understandably draws more visitors than any other Venice landmark. Commissioned by Doge Pietro I Orseolo in 976 and extended thereafter, the lavish Pala d’Oro altar contains enamels taken from Constantinople following the Fourth Crusade. The golden structure incorporates 1,300 pearls, 300 sapphires, 300 emeralds, and garnets, amethysts, rubies, spinels and topazes.

Giorgione’s La Tempesta (around 1505), Gallerie dell’ Accademia

Giorgione, La Tempesta (around 1505)

This work is not only one of the world’s first landscapes; it is also the most mysterious painting in Venice. Giorgione moodily depicts a green and turquoise countryside illuminated by a burst of lightning. The man to the left has been variously identified as a shepherd and a soldier, while the nude woman suckling a child is sometimes described as a gypsy. Whether the work represents a socio-political allegory, a symbolic narrative or pure fantasy depends on who you ask. It is displayed at the Gallerie dell’Accademia, a temple to Venetian School artists including Bellini, Tintoretto and Titian.

Veronese’s Madonna in Glory with St Sebastian (1572), Church of San Sebastiano

Veronese, Madonna in Glory with St Sebastian (1572)

The sober Renaissance façade of the church of San Sebastiano hides a trove of works from Veronese’s mature period. Depicting scenes from the saint's life, the artist's cycle of frescoes and paintings extends across walls, ceilings and panels in the organ loft. The Madonna in Glory with St Sebastian, which was beautifully restored in 2017 along with the church's other works by the non-profit organisation Save Venice, takes pride of place above the church’s altar. Veronese worked on the paintings for over 20 years and is buried in the church.

Tiepolo’s Neptune Offering Gifts to Venice (around 1758), Doge’s Palace

Giovanni Battista Tiepolo, Neptune Offering Gifts to Venice (around 1758)

In the Doge’s majestic seat of power, the gilded Sala delle quattro porte linked the four principal organs of government (the Sala del Collegio, Sala del Senato, Sala del Consiglio dei Died and Sala dei Tre Capi). Commissioned to replace a fading Tintoretto fresco, Tiepolo’s allegory extols Venice’s wealth and domination of the sea. Venice is depicted as a beautiful Queen leaning on a lion of St Mark. Neptune, god of the sea, offers her gifts from a cornucopia overflowing with coins, coral and pearls.

Jackson Pollock’s The Moon Woman (1942), Peggy Guggenheim Collection

The Peggy Guggenheim Collection houses Jackson Pollock'sThe Moon Woman (1942)

In addition to its museums in New York and Bilbao, the Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation also manages the Peggy Guggenheim Collection, displayed in the heiress’s former Venice home. The 20th-century collection of Cubist, Surrealist and Abstract Expressionist works includes a number of Jackson Pollocks that fill an entire room. Clearly inspired by Picasso, whose works had shown at MoMA in 1939, Moon Woman depicts a garishly coloured, voluptuous creature with colourful folds of skin wrapped around a jet black spine.

Titian’s Pesaro Madonna (1519-26), Basilica of Santa Maria Gloriosa dei Frari

Titian, Pesaro Madonna (1519-26)

Titian depicts his patron Jacopo Pesaro, then Bishop of Paphos in Cyprus, as kneeling at the feet of the Madonna alongside members of his family, saints, a knight, two prisoners and a turbaned Turk. The artist broke with the tradition of placing devotional figures at the centre of the composition to permit a stronger sense of movement. Continue your Pesaro pilgrimage by checking out the three family tombs in the basilica (containing the remains of Jacopo Pesaro, Doge Giovanni Pesaro and general Benedetto Pesaro). Composer Claudio Monteverdi, Titian and Canova’s heart are also entombed here.

Canova’s Daedalus and Icarus (1779), Museo Correr

Antonio Canova, Daedalus and Icarus (1779)

Overlooking Piazza San Marco, the Museo Correr is housed in parts of the Procuratie Nuove, completed in the 17th century, and the Procuratie Nuovissimi, constructed by Napoleon following the demise of the Republic at the start of the 19th century. On display is Canova’s first marble sculpture, which shows an elderly Daedalus, his body shrivelled with age, attaching wax wings to the back of his son, Icarus. The museum also contains works by Antonello da Messina, Carpaccio and Bellini, as well as maps, architectural designs and models illustrating the history of Venice.