The British Museum in London is the latest in an increasingly long line of major cultural institutions to scrub from their walls all reference to the Sacklers—the philanthropic family now indelibly linked to the US opioid epidemic.

Members of the family manufactured and aggressively marketed the addictive prescription painkiller OxyContin. But before the dangers of the opioid drug were fully known, the Sacklers rose to prominence as generous patrons of arts and educational institutions on both sides of the Atlantic. Those same museums and universities are now rushing to disavow the family name.

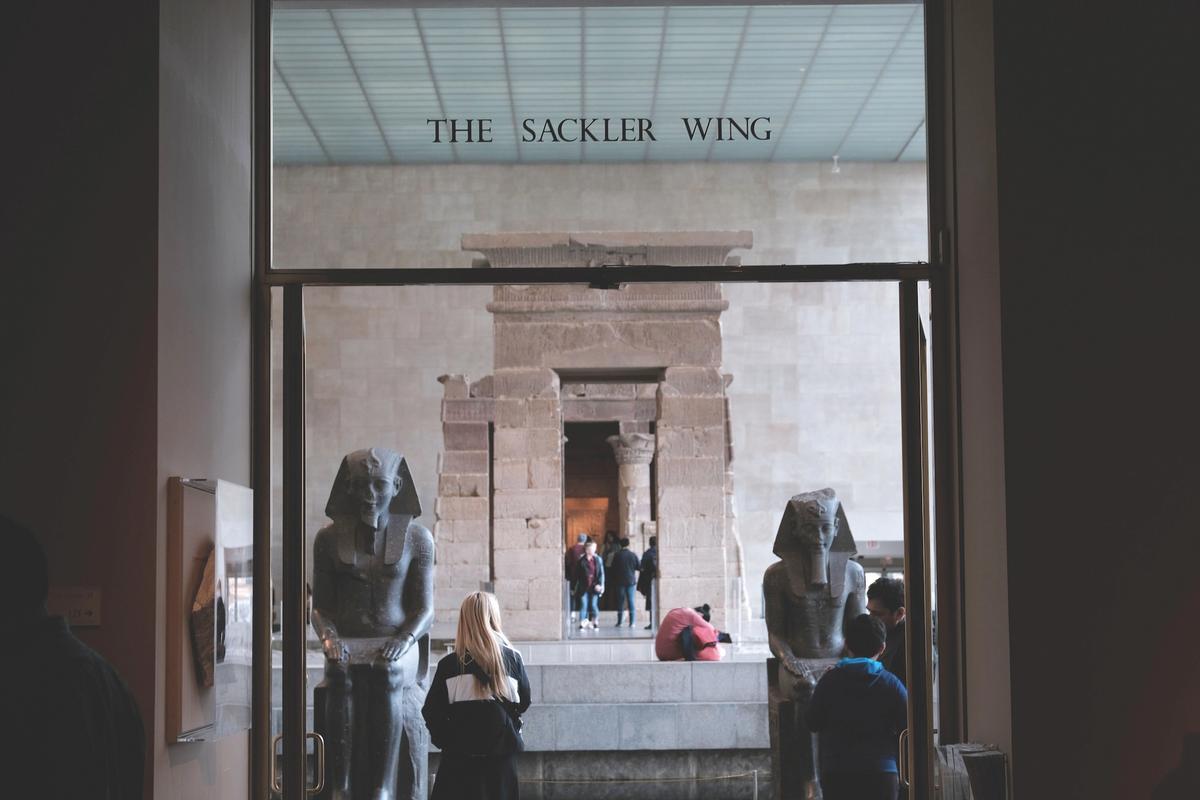

In February, the Tate also announced it would remove references to Sackler philanthropy from its two London museums. It followed the Serpentine Galleries in London and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, which took down the Sackler name from their buildings in January and December respectively. The Musée du Louvre in Paris erased references to the family’s donations in July 2019, a decision it attributed to the expiration of a 20-year naming rights deal.

Earlier this month, a $6bn legal settlement was reached between the Sackler-owned firm Purdue Pharma and a consortium of US states that would resolve the barrage of civil lawsuits filed against the family for its role in the opioid crisis. (The Sacklers deny wrongdoing.) The terms of the new settlement would allow museums that have taken Sackler money to remove the family name from physical facilities, programmes, scholarships and endowments without penalty, provided that they give 45 days' confidential notice and do not "disparage the Sacklers". The settlement awaits final approval by a judge and the US Court of Appeals.

Though the Tate, the Met and several other museums declared in 2019 that they would not accept further gifts from the Sacklers, signs and plaques marking the family’s historic donations remained intact—until now.

“The Sackler case is a major milestone in the history of American cultural philanthropy,” says Benjamin Soskis, a senior research associate at the Center on Nonprofits and Philanthropy at the Urban Institute in Washington, DC. “There is a real symbolic potency to their name being removed from the wall of places like Tate and the Met.”

The Sackler name can still be seen at museums including the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Asian Art and Harvard Art Museums in the US, and the Victoria and Albert Museum (where Theresa Sackler was a trustee from 2011 to 2019) in the UK.

Cautionary tale

Now, the ongoing Sackler scandal raises pressing questions for cash-strapped museums about the future of fundraising. “The Sacklers were exceptional for the amount of money they were willing to give to institutions, and the lack of scrutiny placed on them in terms of how and where they made their money,” Soskis says. Their association with leading museums has now become a cautionary tale in the sector, he says. “Cultural institutions are being forced to think much more carefully about who they accept money from, and how that relates to the values that they espouse.”

When a wealthy donor agrees to support an institution in return for naming rights, the lawyers increasingly draw up contracts with carefully worded “morals clauses”. Such clauses “allow an institution to protect themselves in the event of a donor falling from grace”, says Terri Lynn Helge, a professor of law who specialises in non-profit organisations at Texas A&M University School of Law.

This is a relatively new—and rapidly evolving—phenomenon. “Morals clauses are becoming a lot more frequent,” Helge says. “Fifty years ago, it didn’t even cross the minds of institutions to include them.”

According to Soskis, the shift is in part a result of growing activism from the artist community. “Artists are increasingly working together to insist that they have a seat at the table in considerations of donor policy,” he says. “They’re pushing institutions to rethink naming rights.” The artist Nan Goldin, a former OxyContin addict, has notably led the campaign against the Sacklers’ cultural patronage. In a letter she initiated last November, more than 70 artists including Kara Walker and Ai Weiwei called on the Met’s board to strip the family name from its walls.

The Sacklers are not the only scandal-hit philanthropists to have brought scrutiny on the museums they support. Last June, Leon Black resigned as chairman of the Museum of Modern Art in New York after revelations became public of his close professional association with the convicted sex offender Jeffrey Epstein. And in 2015 the Smithsonian sought—unsuccessfully—to conceal a $716,000 donation from the comedian Bill Cosby, who was accused of rape and sexual assault by dozens of women (Cosby’s 2018 conviction was overturned last year).

“There’s been an accumulation of stories of major figures falling from grace that has led institutions to rethink how they conduct gift agreements in the future,” Helge says.

Morals clauses are not yet prevailing practice, however.

A week before Jeff Bezos blasted into space on his New Shepard rocket last July, the Smithsonian Institution announced the billionaire Amazon founder’s $200m donation to the National Air and Space Museum in Washington, DC—the largest gift ever made to the federally funded institution since it was established in 1846. Though the legal intricacies of naming gifts are usually kept private, the terms of Bezos’s agreement with the Smithsonian were released to US media in February under a public records request. Bezos’s name will be given to a new $130m education building and displayed in several other places throughout the museum, including etched into a glass sculpture that will hang from the ceiling.

Significantly, the contract does not include a morality break clause, meaning his naming rights will be legally protected for 50 years—regardless of whether Amazon becomes mired in corporate scandal.

Donors in the driver’s seat

“I presume Jeff Bezos is giving so much money and has so much leverage and has such good and aggressive lawyers that he can insist that no morals clauses are included,” says Jeffrey Tenenbaum, a non-profit attorney and managing partner of the Washington, DC-based Tenenbaum Law Group. “The donor is usually in the driver’s seat in this kind of situation.”

The world’s second-richest man wields the influence to define the terms of his own naming rights, Tenenbaum suggests. “My guess is, if Bezos were ever to agree to a morals clause, it would be very narrowly crafted,” he says. “So he would have to be guilty of the worst of the worst kind of behaviour. And it would have to be proven to have occurred as opposed to just an allegation.”

The Bezos case points to a larger issue for museums. “Crafting a morals clause is easier said than done,” Helge says. “The trigger of when it is permissible for the museum to disassociate from the donor is really important. I’ll use Bill Cosby as an example: you don’t necessarily want to have to wait until there’s been a conviction of the alleged crime before you can then disassociate yourself.”

But museums must strike a delicate balance in negotiating with prospective deep-pocketed donors. “On numerous occasions, we’ve seen initial allegations against a high-profile figure prove to be wrong,” Helge says. “So from a donor’s perspective, they don’t necessarily want a museum to be able to act with a knee-jerk reaction to an initial news report.”

“Trying to craft morals clauses that are satisfactory to both the organisation and the donor—I think it’s becoming a more and more difficult task,” she says.

What is more, against a febrile backdrop of trends such as cancel and call-out culture, many institutions are ever more reliant on the goodwill of the wealthy. The transaction of cash gifts for naming rights “has a long tradition in America especially”, Soskis says. “But there’s been a dramatic increase in the last couple of decades.”

The practice is only likely to grow because of the financial strain placed on museums by the pandemic. “After the pandemic, named gifts are potentially even more crucial to museums, even as they grapple with the changing nature of morals clauses,” he says. “That tension has not yet played itself out.”