The unexpected death of Achim Borchardt-Hume at the age of 56 robs his colleagues of a friend and mentor and the wider art world of an exceptionally talented, productive and admired curator. Two exhibitions currently on view at Tate Modern, The Making of Rodin (until 21 November) and Anicka Yi: In Love with the World (until 16 January) have become a poignant testament to his unusual ability both to curate original re-interpretations of familiar ‘Modern masters’ and to collaborate with contemporary artists on ambitious new projects.

Borchardt-Hume was an outstanding example in a generation of European curators who were given an opportunity, through the creation of the European Union, to be born in one country, study in another and work in a third or fourth before reaching the age of 40. Born in Germany in 1965, educated at universities in Bonn, Rome and eventually Essex, Borchardt-Hume was a curator whose professional career played out at the Serpentine Galleries, Whitechapel Gallery and the Tate in London. Like others who have arrived in the capital over the past 25 years, Achim brought a breath of fresh air to the British art world. His education was different, with a wider frame of reference than is conventional amongst historians trained in England. His doctorate thesis looked at the relationship between art and politics in Fascist Italy and in many of his exhibitions and essays he sought to place the achievements of artists in the context of the cultural and political realities of the contemporary world. At the outset of his brilliant, sensuous exhibition Picasso 1932: Love, Fame, Tragedy (2018), examining the production of Picasso during a critical year in his career, Borchardt-Hume gently reminded us that this was also the year in which Adolf Hitler was granted German nationality, allowing him then to stand in elections and to take power in 1933.

The EY Exhibition: The Making of Rodin exhibition is on show at Tate Modern until 21 November Photo: © Han Yan/Xinhua/Alamy Live News

I first encountered Achim when he was completing his doctorate at Essex. Over the spring and summer of 1994, in the run up to commissioning an architect to convert the Bankside Power Station into what became Tate Modern, Achim undertook an exercise to solicit the views of a wide range of living artists on the essential attributes of a good space for art and the successes and failures amongst recently completed museum and gallery buildings. His persistence and rigour elicited some valuable responses and did much to shape thinking that eventually led to the appointment of the architecture firm Herzog and de Meuron and the use of the Turbine Hall as ‘found space’. Already, at the age of 30, his promise was evident.

There was nothing predictable about Achim’s exhibitions, other than the fact that they would deliver a fresh take on the well-known

There followed a period as an assistant curator at the Barbican and six years at the Serpentine where he worked on solo shows with artists including Stan Douglas, Gillian Wearing, Rachel Whiteread, Cindy Sherman and Yayoi Kusama. In 2005 he became a curator at Tate Modern, returning to his abiding interest in Modernism with the exhibition Albers and Moholy-Nagy: from the Bauhaus to the New World (2006), an original concept for an exhibition that traced the work of two of the most influential teachers at the Bauhaus through their departure from Europe to their impact on schools of art and design at Yale and Chicago. The next year Borchardt-Hume’s ability to work with artists was put to the test in collaborating with Doris Salcedo on the realisation of one of the most ambitious and challenging transformations of the Turbine Hall. The introduction of a massive fault line, or ‘crack’ along the length of the space was an exceptional feat of engineering and all of Achim’s tenacity was required to deliver Shibboleth on time. Further, well selected and beautifully paced exhibitions of the late work of Mark Rothko and the painter Per Kirkeby followed in successive years.

In 2009 Borchardt-Hume’s growing authority as a curator led to his appointment as chief curator in the newly expanded Whitechapel Art Gallery. Over the next three years, he broadened his field of interest to look at artists working in the Middle East and elsewhere in the world, curating an astonishing number of significant exhibitions for, amongst others, Mel Bochner, Giuseppe Penone, Zarina Bhimji and Walid Raad. He returned to Tate Modern as head of exhibitions in 2012. Achim was always eager to learn from the experience of others and worked well with the then director, Chris Dercon as he had done in his earlier phase as a curator at Tate Modern working with Vicente Todoli. Major exhibitions that he curated over the next few years included Malevich in 2014, Alexander Calder: Performing Sculpture in 2015-16, Robert Rauschenberg in 2016 and Picasso 1932 in 2018 in close collaboration with colleagues at Tate Modern, as was so often the case with his projects. All, like the current Rodin show, were distinguished by their original scholarship, their careful inclusion of archival material and historical context, their structural clarity and thoughtful pacing. There was nothing predictable about Achim’s exhibitions, other than the fact that they would deliver a fresh take on the well-known.

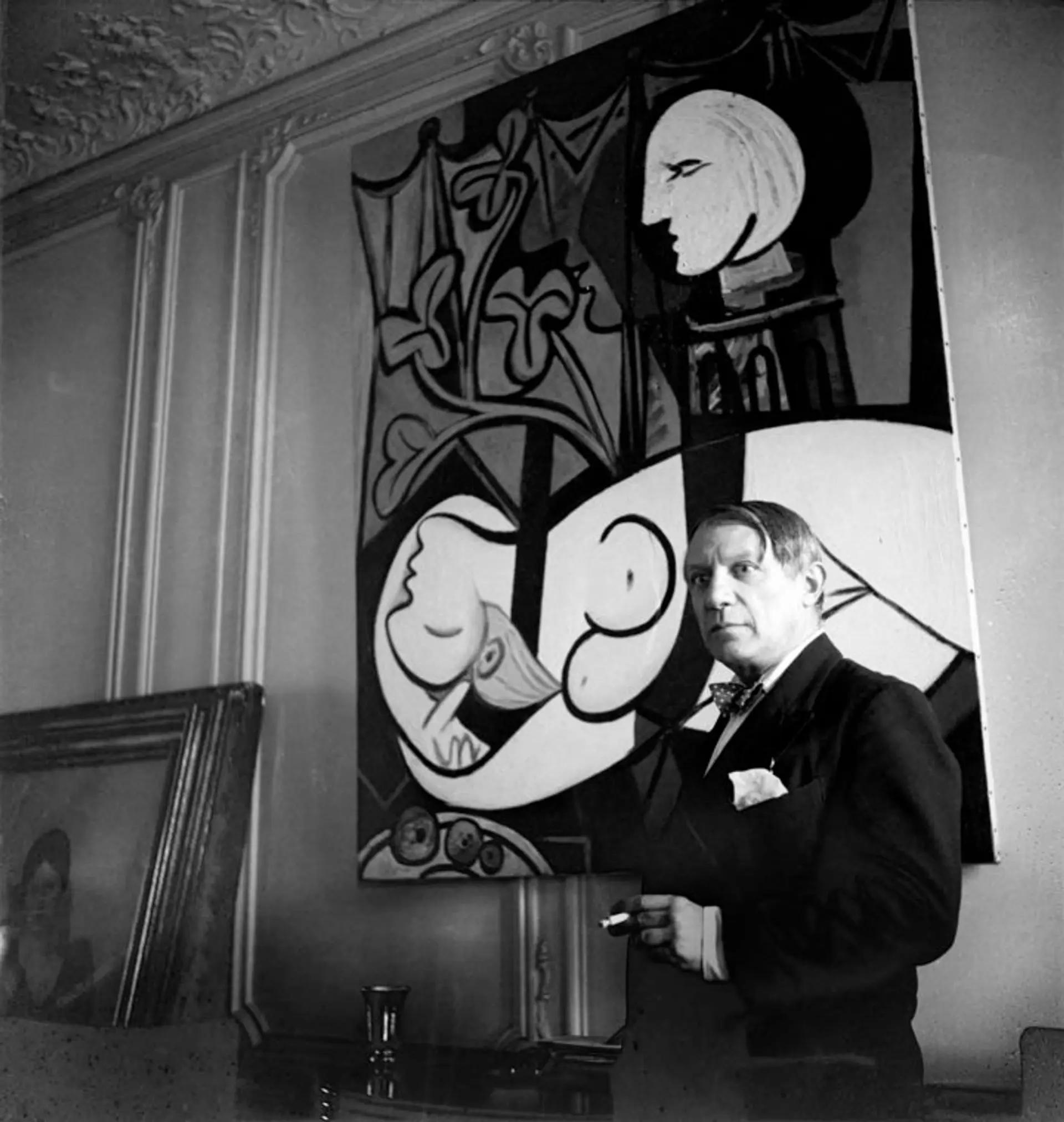

Picasso 1932 included three works of his teenage muse and lover Marie-Thérèse Walter, seen here in the background in a photograph taken by Cecil Beaton © The Cecil Beaton Studio Archive at Sotheby's

In recent years, Borchardt-Hume assumed responsibility for oversight of the overall programme of Tate Modern, working with the current director and close friend Frances Morris to guide the curatorial, learning and live performance teams. He also contributed hugely to Tate as a whole, championing the interests of the BAME staff network and supporting staff through the challenges brought about by the pandemic. A frequent panellist, jurist and moderator at symposiums in London and abroad, his contribution as an historian and his judgement as a curator were increasingly sought both in England, where he was for some years a trustee of Peer in Hoxton, and in continental Europe, where he served on the advisory board of the Generali Foundation in Vienna. Occasionally he also undertook independent projects, such as the important exhibition of Gerhard Richter’s overpainted photographs shown in Beirut in 2012. On more than one occasion he turned down opportunities to lead major institutions in his native Germany, though his loyalty to his adopted home was tested by Brexit and the encroaching insularity of political debate in England.

His untimely death leaves an enormous gap in London. As a professional, Achim was profoundly serious, continually questioning convention and using his disarming charm to win his point with a difficult lender, or an artist who was pushing the boundaries. A knowing smile would often accompany a mischievous or ironic comment from a curator who saw the world from a truly cosmopolitan viewpoint. In recent years he had developed a rare capacity to share his sensitivity, his wisdom and his experience with colleagues at home and abroad. There will be deep grief at his passing within Tate and across the world.