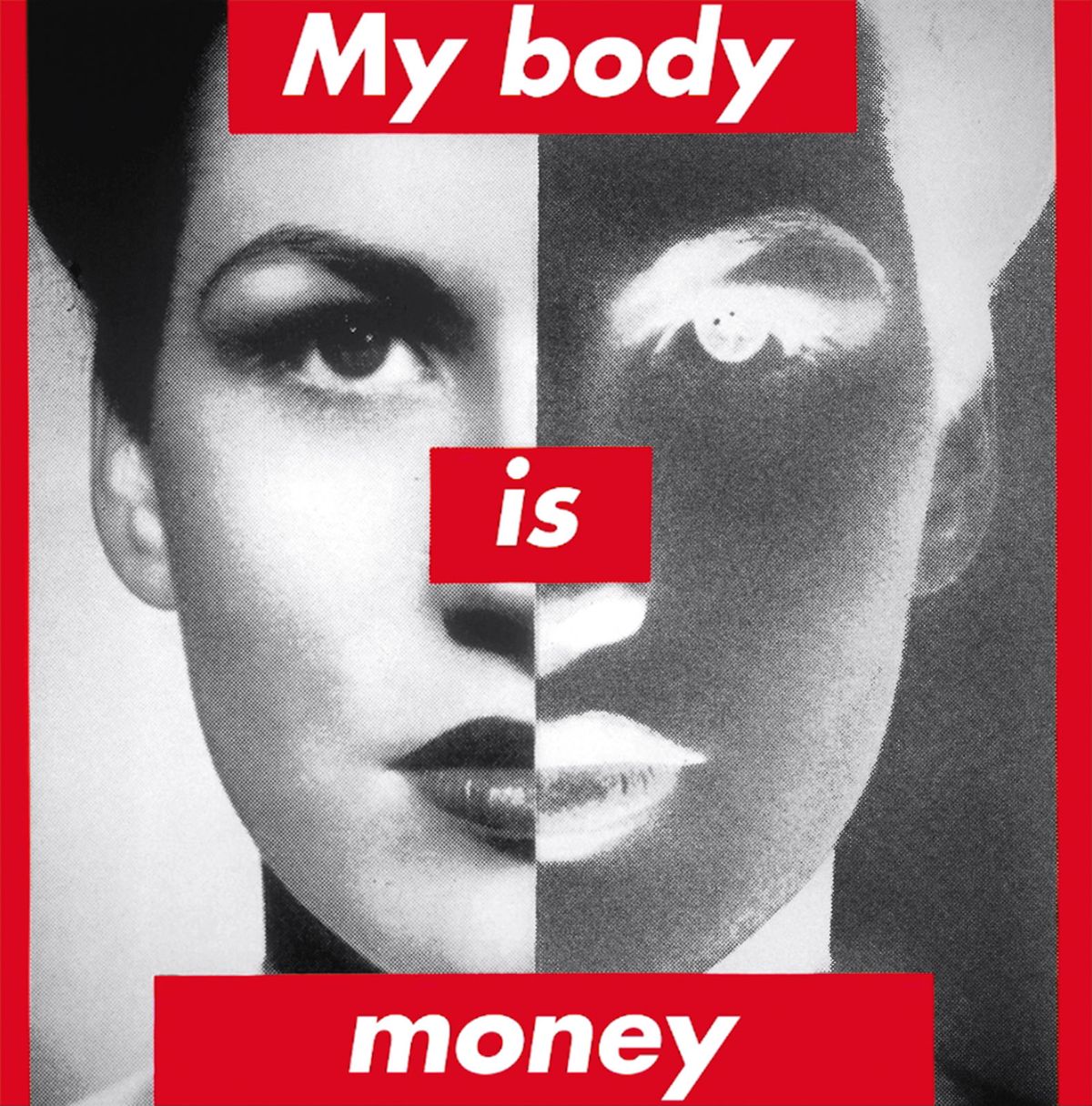

By some measures, Barbara Kruger might be the most influential artist working today. Her cliché-eviscerating work has moved as ably as cliché, infiltrating visual culture to an extraordinary degree, with early pieces like Untitled (I shop therefore I am, 1987) and Untitled (Your body is a battleground, 1989) spawning countless imitations and variations.

But far from assuming that influence works in one direction, Kruger’s work often acknowledges that she is not only a creator but a consumer, speaking to other consumers who in turn speak to her—even with their knock-off versions of her works. And she knows that artists are perpetually remaking their own work.

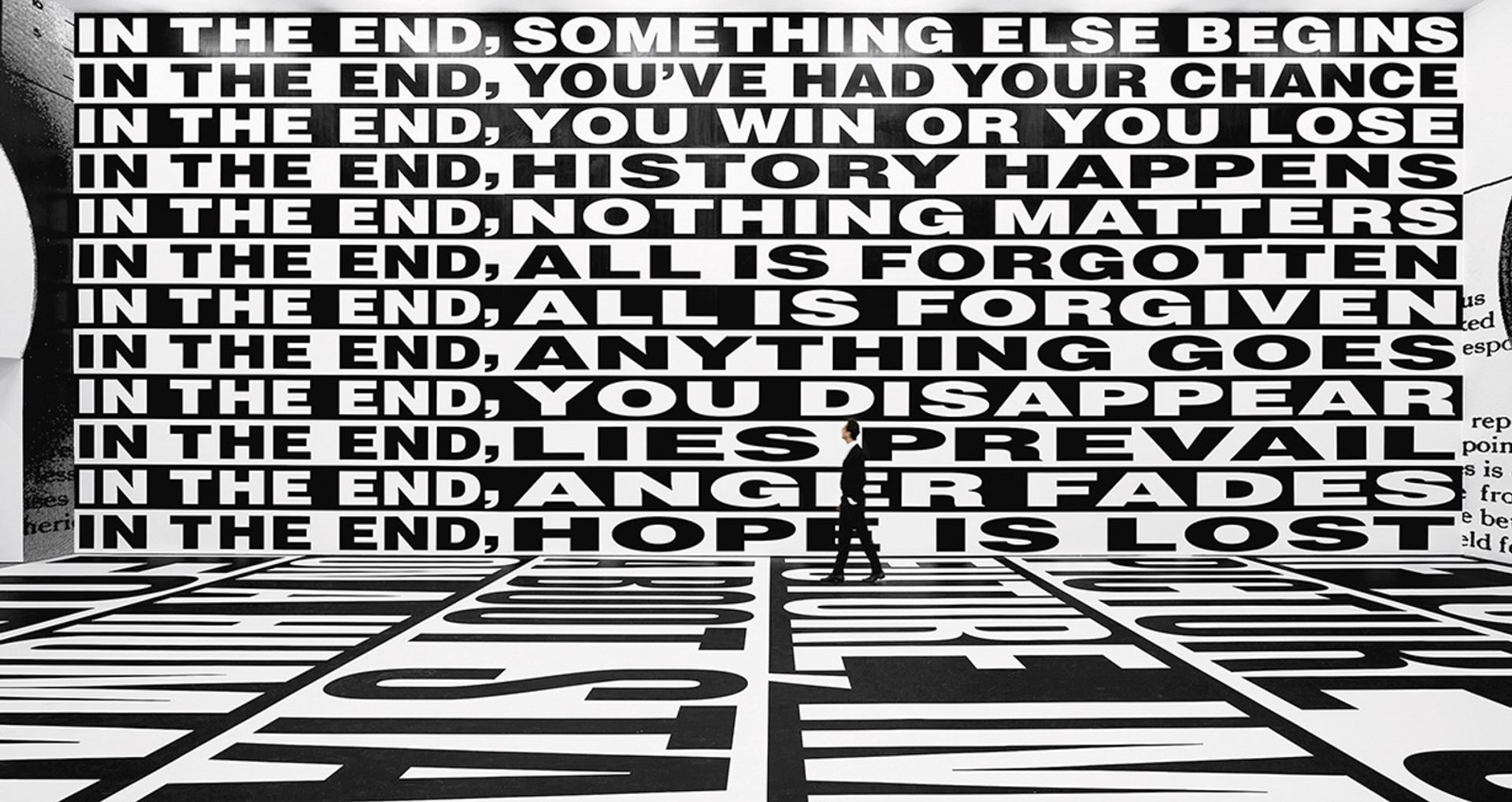

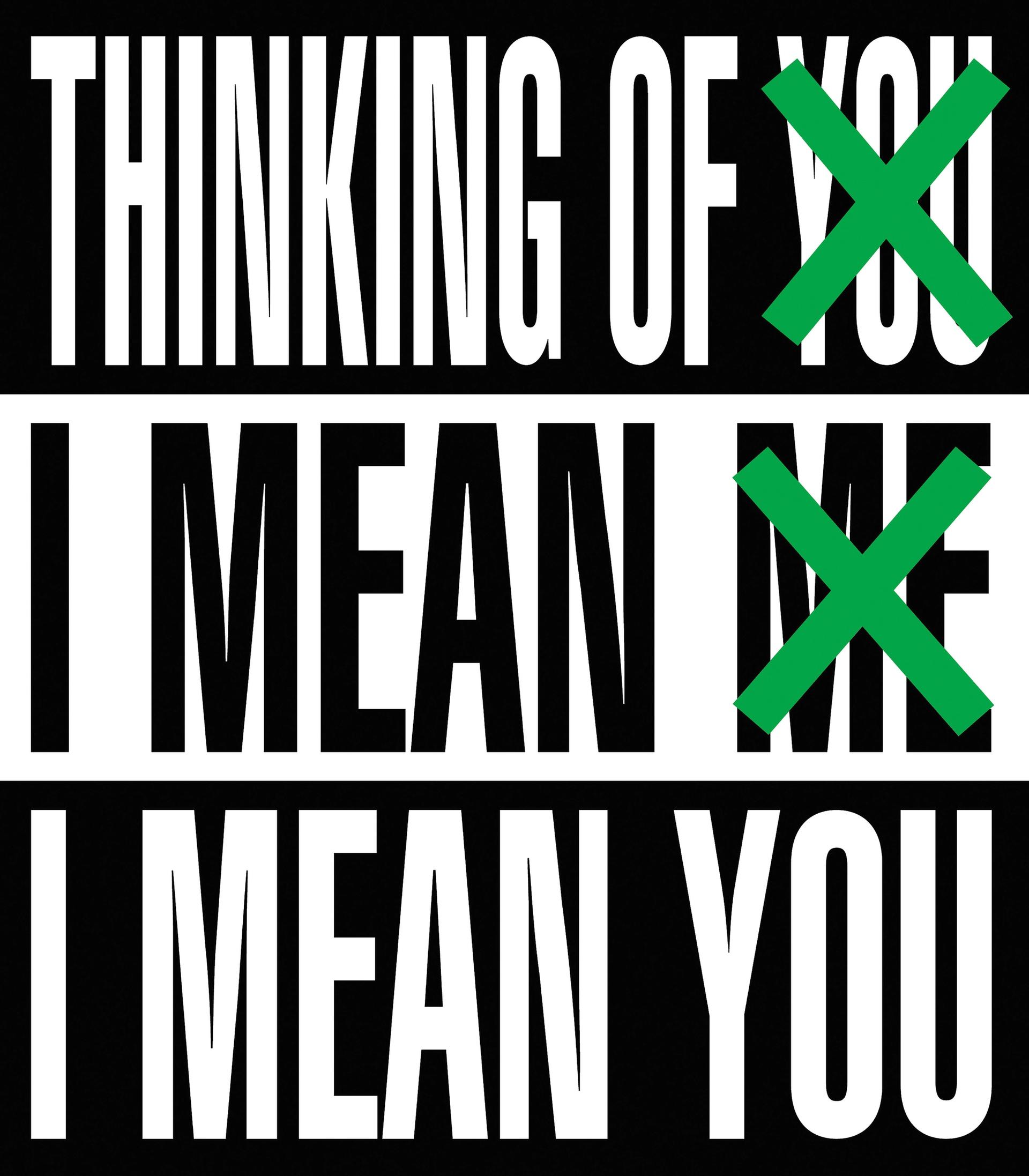

Her forthcoming survey at the Art Institute of Chicago, Thinking of You. I Mean Me. I Mean You, is especially canny in this way, with five new, large LED displays that revise her early catchphrases. Together, they replace the notion of the “icon” as a static image with something more fluid and alive—something more like a meme.

The Art Newspaper: You have called your new show an “anti-retrospective”. What do you mean by that?

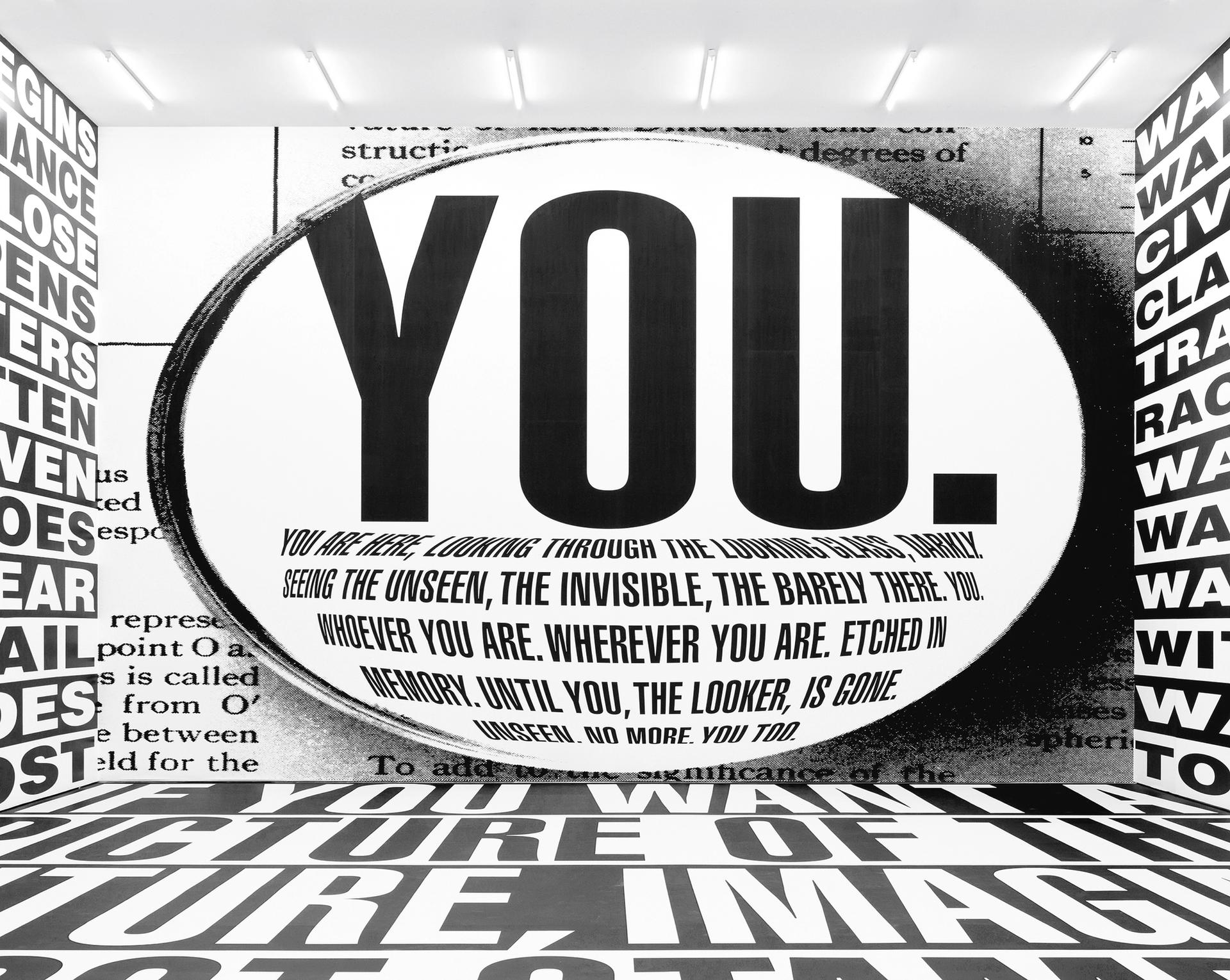

Barbara Kruger: I don’t really remember saying that because it’s so binary. It’s more that this show is not a gathering together of all of my works. There aren’t that many works where you can put a nail on the wall and hang something. It’s mostly wallpaper and floors, architecturally determined by the space. In Chicago, the show will look totally different than it will when it travels to Lacma [Los Angeles County Museum of Art], which will look different than what I will do in the atrium at MoMA [Museum of Modern Art in New York]. It’s all architecturally defined, and that’s what I love doing.

Barbara Kruger's Untitled (Forever, 2017). Installation view at Sprüth Magers, Berlin, in 2017-18 Amorepacific Museum of Art (APMA), Seoul. Photo: Timo Ohler and courtesy of Sprüth Magers

The survey also has a mural showing different ways people have riffed on your images. Does it surprise you that your work has taken on such a life of its own?

Some of my early works came out of the fluency I learned working as an editorial designer [starting in the 1960s at Mademoiselle magazine], that was obviously pre-digital. People turn pages quickly, and if you could get somebody to stop and stay on a page for a while with a quick thought or look, that was good. That’s why many of these works have another life in a digital universe, where folks can take forms and make them their own.

Have you ever sued anyone for copyright infringement?

I’m on this website Redbubble, where people design posters and t-shirts, and sometimes my gallery asks them to take things down and they will. So I’m not against copyright. But I don’t own a typeface. I don’t sue people. I will let all these corporations who are old-school robber barons do that. I think copyrights are euphemisms for corporate control on a certain level. Remember when Napster lost its first big lawsuit and the record industry thought it won? Guess what? It didn’t. We live in this digital universe. Digital life has been emancipating and liberatory but at the same time it’s haunting and damaging and punishing and everything in between. It’s enabled the best and the worst of us.

Untitled (Forever, 2017) appeared in a 2019 show at the Amorepacific Museum of Art Photo by Timo Ohler, courtesy of Sprüth Magers

You made Untitled (Your body is a battleground) before the march in Washington, DC in 1989 supporting abortion rights. Can you tell us how the work came about?

At that point in 1989, I think I had been to two previous huge marches in DC to protect women’s reproductive rights. We thought we had done this in 1973 [with Roe v Wade, the Supreme Court decision on abortion], and here it was in 1989 and it was still happening. I reached out to [pro-choice organisations] Planned Parenthood and NARAL and offered my services, but one of them said we already have an advertising agency we are working with. They didn’t know who I was; I barely knew who I was. So I printed this work myself and went around with my students at the Whitney Independent Study Program and sniped it—posted it—throughout Manhattan.

And of course this work is still so urgent today, and still being used.

Just this year it was used in a project in India about women’s menstruation [called Sanitation First]. There is a crisis in India right now—not just Covid but also because of discrimination based on poverty, class, caste and gender—so they approached me to see whether they could use Your body is a battleground as a template. This was a campaign to talk openly about women’s bodies and supply sanitary products.

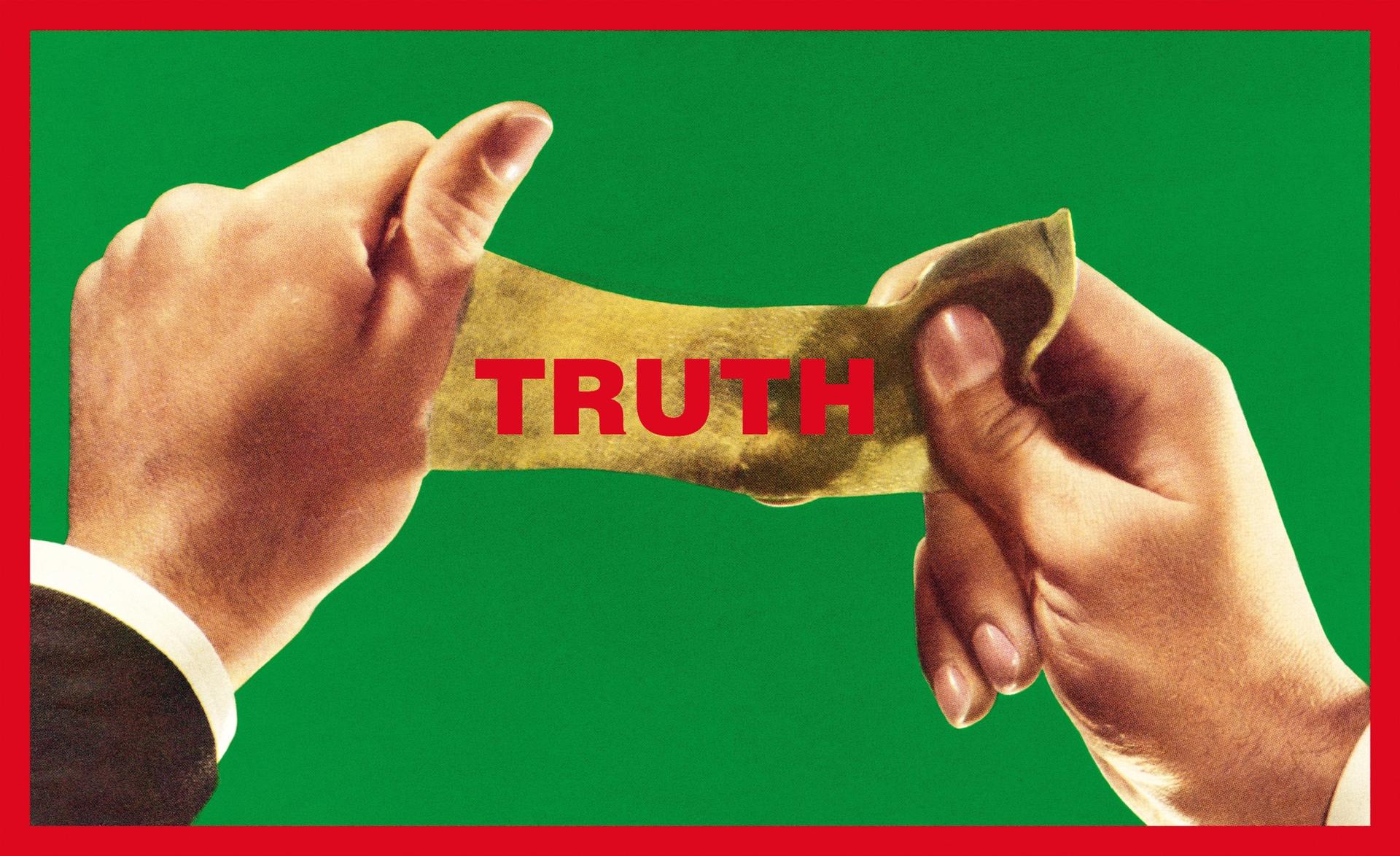

Barbara Kruger. Untitled (Truth, 2013) Collection of Margaret and Daniel S. Loeb. Digital image courtesy of the artist

You must get hit up to make or donate work all the time for causes.

I get dozens and dozens of emails every month, but I couldn’t possibly produce that much. As you might know, I have no assistants. It’s just me.

Right before the 2016 presidential election, you made a New York magazine cover where you slapped a red bar with the word “loser” across a close-up of Trump’s face—using one of his favourite insults against him.

That was the point—I was trying to think of the word that he most fears in his life. This was not a prediction of the election by any means. There was no way I thought he was going to lose. I’ve been watching that guy and listening to him for 35 years on The Howard Stern Show and The Apprentice. I know what he’s capable of and what he does, he does really well. The Republican men are full of fire and brimstone—they know how to speak their rage. Not so many Democrats have rhetorical gifts.

Has a politician ever asked you to help with their messaging?

Not really. And I would not do a poster for any particular campaign. It just narrows the meaning down, and I have problems with how candidates are chosen. In 2016, I did a print edition along with other artists to raise money for the Democratic candidate, Hillary Clinton, using a quote from Karl Kraus: “The secret of the demagogue is to make himself as stupid as his audience so that they believe they are as clever as he.” But it was not a Clinton poster; it was about defeating Donald Trump.

Speaking of abuse of power, your work often gets discussed with Jenny Holzer’s because you share that theme, plus interests in language and making your work accessible through materials like posters or stickers. What is the biggest difference between your work and hers?

We share an understanding of how power circulates through culture, how it bestows on some and withholds from others. All these categories, like Pictures Generation and appropriation art, I can’t stand that. I was never a part of the Pictures Generation until that show at the Met [in 2009]. I feel closer on a certain level to Jenny’s methods of address. The differences happen visually from work to work and in my longstanding investment in the reproduction of images.

You curated a small show at MoMA in 1988 called Picturing “Greatness”, with photos of artists, almost all white men, like Rodin and Picasso. I understand you are doing a new version at the Art Institute?

I went through the MoMA photo archive at a time when [the curator John] Szarkowski was still there, and there were almost no women in it. In the Art Institute of Chicago archives, there are more people of colour and women, so I changed the text on the wall a little to mention this incremental change. But the show is still a critique of the notion of greatness. In the title Picturing “Greatness”, the word greatness is always in quotes. As I’ve said before, I don’t believe that any work, whether it’s a piece of visual art or a novel or a building, is as brilliant and major and extraordinary or as damaged and pathetic and minor as it’s thought to be.

Barbara Kruger's Thinking of You. I Mean Me. I Mean You. (2019) Digital image courtesy of the artist

You requested that we not publish a portrait of you, which strikes me as an act of feminist resistance. But I wanted to ask you directly: what’s at stake for you in this?

The texts I wrote for Picturing “Greatness” will tell you. If my image or portrait has to be reproduced in an article, I don’t want to be included at all. There are images floating online and that pisses me off. I want my work to speak for me. Thank God I’m an artist and not an internet or TikTok or movie star; any time I go to a gala, all those people are fighting to get on the red carpet, but the photographers don’t give a flying fuck about artists.

And is there a reason you don’t post on Twitter and Instagram and such?

I have friends who are writers and use Twitter or Instagram as a public relations tool: this is what I read or this is what I eat, so this is what I am. But I’d rather go to hell than do that about myself. Really, everyone is needy in different ways.

Biography

Born: 1945 Newark, New Jersey

Lives: Los Angeles

Education: 1964-65 Syracuse University, New York; 1965 Parsons School of Design, New York

Key shows: 2019 Amorepacfiic Museum of Art, Seoul; 2016-17 National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC; 2013-14 Kunsthaus Bregenz, Austria; 2000 Museum of Contemporary Art Los Angeles

Represented by: Sprüth Magers, Los Angeles, London and Berlin; David Zwirner, New York

• Thinking of You. I Mean Me. I Mean You, Art Institute of Chicago, 19 September-24 January 2022. Tours to Los Angeles County Museum of Art and the Museum of Modern Art, New York, in 2022