A row has broken out after a new documentary on the world's most expensive painting, the Salvator Mundi, claimed that the Musée du Louvre doubted the painting's attribution as a 100% autograph work by Leonardo da Vinci. Although the museum has not publicly commented on the film's assertions, an unpublished booklet on the Louvre's scientific examination of the painting has been leaked to several media outlets, contradicting the film's conclusions.

In the film, The Savior for Sale, broadcast on French television tonight, two anonymous officials in French President Emmanuel Macron’s government make the claims that the Louvre questioned the attribution.

The comments relate to a top-secret examination of the picture, conducted by the Louvre’s laboratory in June 2018, which, these officials say, concluded that Leonardo “only contributed” to the work. As a result, they assert that the Louvre wanted to label it as “Leonardo and studio” in their landmark Leonardo exhibition, which ran from October 2019 to February 2020.

But, according to the film, the painting’s owner, the Crown Prince of Saudi Arabia, Mohammed Bin Salman (MBS), who bought the work via a proxy from Christie’s New York in November 2017, apparently insisted that it be labelled as "100% Leonardo" and placed next to the Mona Lisa. When President Macron rejected these conditions, MBS refused to loan the picture, the film alleges.

A secret booklet, “Léonard de Vinci: Le Salvator Mundi”, prepared by the Louvre and printed in December 2019, roundly contradicts the film’s findings. The booklet provides detailed conclusions of the Louvre’s precise scientific examinations, and concludes that—contrary to the claims made by the two officials in the film—“The results of the historical and scientific study … allow us to confirm the attribution of the work to Leonardo da Vinci", the museum's director, Jean-Luc Martinez, wrote in its preface.

The Art Newspaper discovered the existence of the 46-page booklet back in March 2020 and reported its affirmative conclusions. Though the book was never distributed, a Louvre spokesperson confirmed at the time that “the book was prepared in case the Louvre got the chance to present the painting. As this has not been the case, it is not going to be published”. The Art Newspaper also reported further on the book’s findings in January this year. But the film unfortunately does not address this vital element of the story.

The book that never was – and is no longer to be found

We asked the film’s director, Antoine Vitkine, to comment on this omission. He explains: “Following your revelations about the secret book, I contacted Martinez, who explained that the Louvre does not talk about pictures it does not own and it doesn't have the right to research pictures that don't belong to national collections. The Louvre’s official line is that the book ‘doesn’t exist’. My film’s focus, however, was an investigation into a political decision made by Macron in September 2019, so I concentrated on that. I am very respectful of the Louvre’s scholarship, and I can’t explain the contradictions between the dossier that went to Macron concerning the Louvre’s findings and the secret book, which was paid for by Saudi Arabia. I am confident, however, that [President] Macron did not have access to it when he made his decision.”

Vitkine adds: “But you cannot underestimate the political pressure—in terms of both the Louvre’s interests and the interests that France has in Saudi Arabia—which, without casting any aspersions, pollute what should be a neutral artistic and scientific debate by highly competent people.”

When asked whether Saudi authorities paid for the book, the Louvre maintained its consistent position, by declining to comment specifically on the publication. However, a spokesperson was able to say that “the Louvre's scientific contents, whether in its publications or for the purpose of its exhibitions, are of course totally independent.”

The situation regarding the film seemed serious enough that Jean-Luc Martinez was reported to have met in recent days with the Saudi Ambassador to explain the museum’s position. A few days before the airing of the documentary on French television, several news outlets such as the New York Times and La Tribune de l’Art suddenly had access to the suppressed booklet and published some of its most eye-catching conclusions.

What is in the book?

Given the controversy surrounding the painting and the Louvre’s refusal to comment on the Salvator Mundi or its own book about it, we have decided to report the book’s contents in greater detail.

Published by Hazan éditions—and very temporarily available in the Louvre bookshop in December 2019—it is written by Vincent Delieuvin, the chief curator of paintings at the Louvre, and Myriam Eveno and Elisabeth Ravaud from the Louvre’s laboratory, C2RMF. The book has a cardboard cover, in the style of Louvre catalogues, and is comprehensively illustrated with x-rays and infra-reds taken by the laboratory to support its arguments.

In Martinez’s preface, the answer to the question of attribution is presented categorically: “To mark the celebration of the 500th anniversary of the death of the artist in France, the Louvre museum has organised a major retrospective which intends to offer a complete synthesis of his work. It is in this context that Salvator Mundi, formerly in the Cook Collection and now owned by the Ministry of Culture in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, was studied by the museum and by the C2RMF in 2018. The results of the historical and scientific study presented in this publication allow us to confirm the attribution of the work to Leonardo da Vinci, an appealing hypothesis which was initially presented in 2010 and which has sometimes been disputed. Showing the painting alongside other works by the master from the Louvre is therefore a major event for studies of Leonardo and in the history of our museum.”

The ensuing chapters support the positive attribution to the master. Delieuvin concludes that all the elements the Louvre has studied “invite us to privilege the idea of a work that is entirely autograph ”. Eveno and Ravaud in their section also reach the same conclusion: “The examination of the Salvator Mundi seems to us to demonstrate that the painting was indeed executed by Leonardo…”

The first section of the book consists of a detailed essay by Delieuvin. This would no doubt have made its way into the catalogue of the Louvre’s Leonardo exhibition if the Saudi Crown Prince had permitted the painting’s loan. The Louvre withdrew the book from circulation, and would not discuss it, because the museum is not permitted to write about works that it has not displayed in its galleries.

Delieuvin’s essay examines the lack of contemporary documentary evidence for Leonardo’s authorship, the first preparatory studies by Leonardo for a Salvator Mundi (now in the Royal Collection, Windsor Castle), and the 17th-century engraving of a Salvator Mundi by Wencelas Hollar, with the inscription “Leonardo painted it…”. He then discusses 22 extant paintings of the Salvator Mundi subject, mostly attributed to Leonardo’s studio, and the search for a possible Leonardo original. This leads him to a discussion of the attribution to Leonardo of the Saudi picture (formerly Cook collection), first proposed by Luke Syson of the National Gallery, London, in 2011, and on which Christie’s based its sales catalogue entry.

“There were very differing reactions to the attribution to Leonardo proposed by Luke Syson in the catalogue for the London exhibition, which is to be expected considering what a sensational discovery it was,” Delieuvin writes. “A number of specialists accepted the idea that the painting is entirely autographical, while others preferred the idea that it was a collaboration between the master and a studio assistant. They point out beautiful passages, such as the curling hair and hands, as being worthy of Leonardo, alongside surprisingly weak details where they had difficulty in distinguishing between repainting during restoration and the awkward intervention of an assistant. Finally, a minority of historians totally rejected any intervention by Leonardo.”

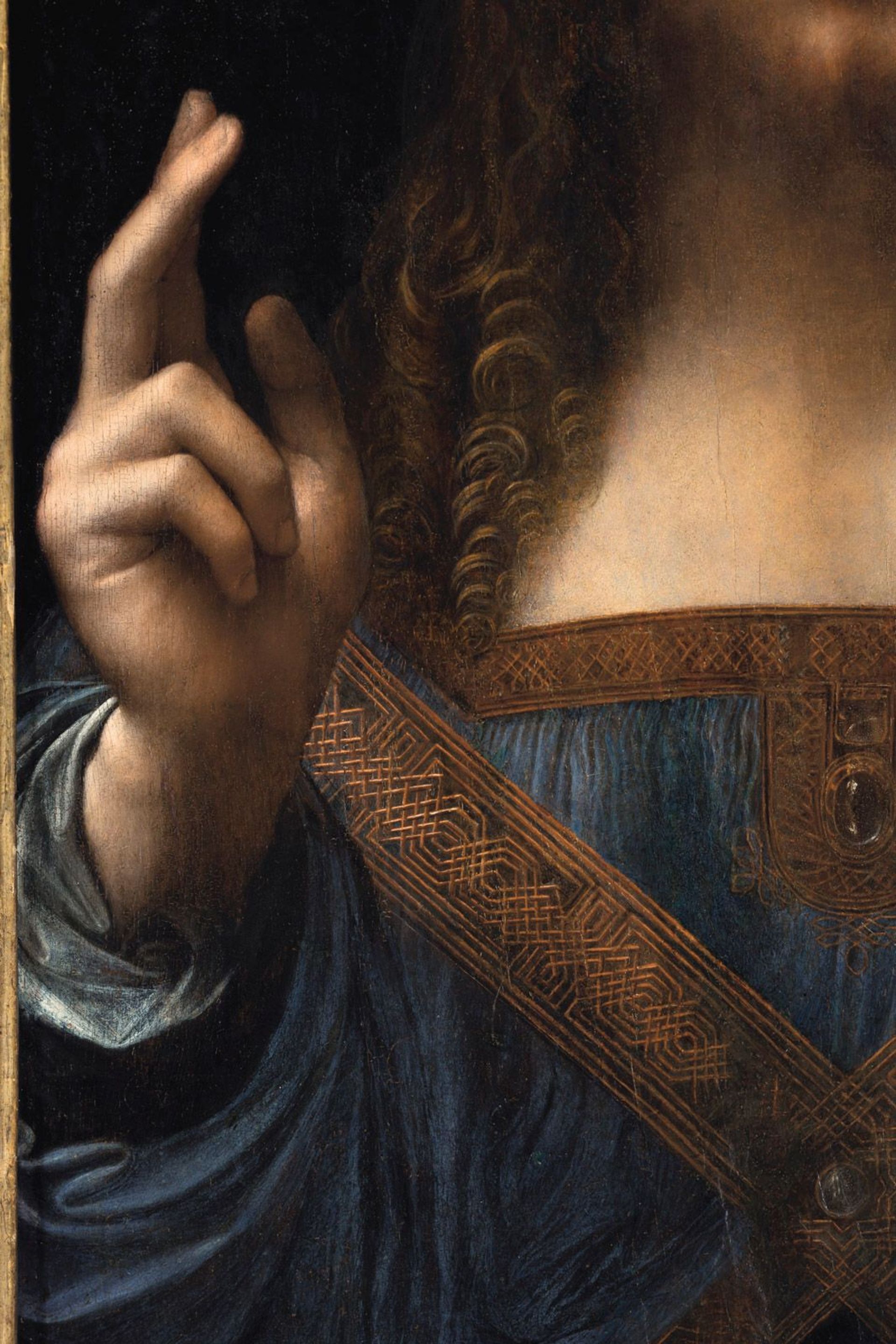

Salvator Mundi's blessing hand

Delieuvin then turns his attention to “the decisive contribution of scientific examinations”. He says that the Louvre’s recent scientific examinations allow them to confirm in particular, the status of the Cook Collection picture (the Saudi Salvator Mundi), despite the extensive damage it has suffered in the course of its history, the fact that its wooden support had been broken into two parts, and the serious paint losses to the central part, which explain, most notably, the ghostly appearance of Christ’s face.

The Louvre findings largely confirm those made by the previous restorer, Dianne Modestini, whose own scientific investigations are published in full on her website. These are much enhanced, however, by the Louvre’s own exhaustive examinations of Leonardo masterpieces in their collection: notably Leonardo’s Virgin and Child with St Anne, St John the Baptist and the Mona Lisa. The latter two are particularly relevant.

The book's key findings:

• The support is walnut, as used by Leonardo and his circle, particularly in Lombardy (Leonardo spent a major part of his career in Milan)

• There is a very fine under-drawing “almost imperceptible” (illustrated by an infra-red ) “which is very close to the Mona Lisa and St John the Baptist. It is clearly different from studio copies, notably the Ganay Salvator Mundi or that in San Domenico Maggiore in Naples, the two closest versions to the [Saudi] painting formerly in the Cook collection, both in their walnut support and their composition.”

• There are already major pentimenti (adjustments); Delieuvin goes on to note the black background to the blessing hand, and the fact that the artist appears to have started the composition without the arm. He also notes the change to the position of the thumb.

• The curls of the hair, the hands and some parts of the mouth and the eyes are magnificent, and endowed with much more volume than the Ganay and Naples versions of the subject. The mouth is favourably compared with that of St John the Baptist.

• "Despite lacunae and abrasions, the best-preserved parts demonstrate a particularly knowledgeable pictorial technique, founded on layers of transparent glazes which enable a subtle passage from shadow to light, to soften the contours (the famous ‘sfumato’) and to highlight the relief of the face. This technique relates to works from Leonardo’s mature period, between 1500 and 1510, such as St John the Baptist.”

The Naples Salvator Mundi (around 1508-13) is attributed to a follower of Leonardo, likely Salaì © SAN DOMENICO MAGGIORE, NAPLES

Following on from this, Delieuvin unpicks the provenance proposed by the National Gallery in 2011, which was used by Christie’s when it marketed the picture as “the property of three kings”. The hypothesis that the picture was originally commissioned by Louis XII of France is considered “weak if not completely false” and the National Gallery’s dating of the picture to around 1500 is not supported. “As to our current state of knowledge, it is impossible to affirm that Louis XII ordered this composition from the artist. In any case, it is very unlikely from 1499, since the documents from the archives that have been conserved demonstrate that it is only after 1507 that Louis XII wanted to obtain paintings from the artist.”

Most importantly, Delieuvin distinguishes the picture from other studio works, including the Ganay version of the Salvator Mundi, which appeared in the Louvre’s Leonardo exhibition. It is differentiated: “by the very subtle underpainting, by the presence of numerous pentimenti and by the extraordinary pictorial quality of those parts that are well conserved”.

“All these factors invite us to privilege the idea of a work that is entirely autograph, sadly damaged by the poor conservation of the work and by previous restorations which were too brutal,” he concludes.

Delieuvin’s essay is followed by a detailed discussion of the scientific evidence by Ravaud and Eveno, in the context of “the attribution to Leonardo that has been proposed”. They describe the non-invasive procedures they employed, and conclude as follows:

“The examination of the Salvator Mundi seems to us to demonstrate that the painting was indeed executed by Leonardo. It is essential in this context to distinguish the original parts from those that have been changed or repainted and this is indeed what was carried out during this study notably by using X florescence. Examination under a microscope revealed very skilful execution, notably in the skin colouring and in the curls of the hair, and great refinement notably in the depiction of the relief of the embroidery [knotwork]."

They continue: "Radiography showed up the same very faint outlines as in the St Anne, Mona Lisa and St John the Baptist, characteristic of Leonardo’s work after 1500. The number of changes made during the creation of the work also plead in favour of an autograph work. The first version of the central ‘plastron’ with a pointed form, is immediately comparable to the central part of the tunic in the Windsor drawing and to our knowledge is not seen anywhere else."

"In addition, the movement of the thumb was also noted in the St John by Leonardo. After intensive studies of the other Leonardo works in the Louvre’s collection it seems to us that a number of the techniques observed in the Salvator Mundi are typical of Leonardo—the originality of the preparation, the use of ground glass and the remarkable use of vermillion in the hair and shadows. These latest elements all plead in favour of a late work by Leonardo, after St John the Baptist, and dating from the second Milan period."

The Ganay version of the Salvator Mundi made it into the Louvre show © Musée du Louvre/Antoine Mongodin

As a footnote to this whole affair, it is worth noting that anyone trying to distinguish categorically between the hand of a master and his studio assistants during the Renaissance period is treading a hazardous path, as Scott Reyburn wrote in the March issue of The Art Newspaper. Reyburn quotes the Renaissance teaching professor Jonathan Nelson, who states “virtually all paintings made by Renaissance masters were made with various degrees of workshop assistance.” Michelle O’Malley, the professor of Renaissance art history at the Warburg Institute, London, agrees, dating our focus on the “heroic, genius artist” as opposed to the norm of Renaissance corporate production back to the late 18th century—the era when the great auction houses Christie’s and Sotheby’s were founded.