A new French feature-length documentary on the Salvator Mundi seems to have solved one of the key mysteries surrounding the enigmatic and controversial painting: why it never appeared in the Musée du Louvre’s blockbuster Leonardo da Vinci show. Antoine Vitkine’s film, which The Art Newspaper has gained exclusive access to, is entitled The Savior for Sale and is released on 13 April.

In the film, an anonymous senior official in French President Emmanuel Macron’s government, codenamed “Jacques”, tells Vitkine that the Louvre’s extensive scientific examination of the painting, conducted in secret, concluded that Leonardo da Vinci himself “only contributed” to the picture, and that its “authenticity” could not be confirmed.

The diplomatic stakes around this verdict could not have been higher. The painting’s owner, the Crown Prince of Saudi Arabia, Mohammed bin Salman (MBS), had acquired the picture (through a proxy) for $450m—the largest price ever paid for a work of art—at Christie’s, New York in November 2017. It had been sold as an authentic Leonardo da Vinci, and had been dubbed “the male Mona Lisa”.

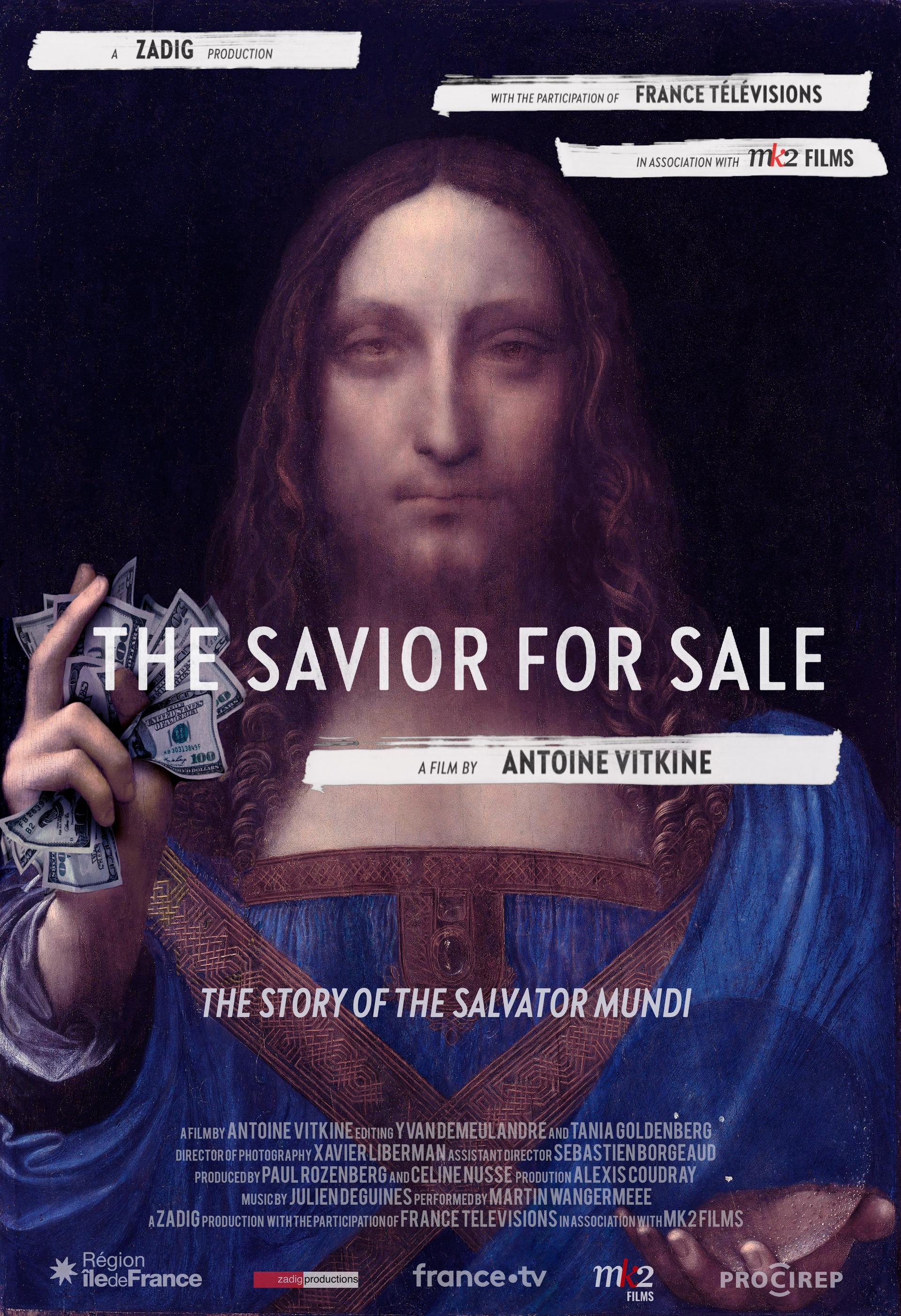

The Savior for Sale will debut on French television on 13 April © Zadig productions/FTV

A further “deepthroat” source in the film—a senior official in the ministry of culture, codenamed “Pierre”—relates how the deal for the Louvre to present the Salvator Mundi was discussed at the major French/Saudi summit of April 2018. This revolved around vital shared interests in the political, intelligence, defence, economic and cultural spheres: “MBS was received with considerable pomp during this visit and the Al-Ula agreement [a ten-year deal, potentially worth tens of billions of euros, that gives France an exclusive role in the project to develop the Al-Ula province as a major cultural centre, heritage site and tourist destination] was signed at this time. There was a considerable emphasis given to heritage in this agreement. It would not be crazy to say that at that moment the decision was taken to entrust the painting to France. The Leonardo da Vinci exhibition was already scheduled …. The Elysée [French presidency] explained it was important for MBS to position himself as someone who was opening up Saudi Arabia culturally and to place himself as a symbol of modernity.”

The senior official, “Jacques”, recalls that, “the painting arrived in Paris in June 2018. I think it came directly from the place in New York where it had been stored since the sale. It remained three months in the Louvre and I saw it then.” By that time, it had been analysed at the Louvre’s technical laboratory (C2RMF) in preparation for its starring role in the Louvre’s Leonardo show (opened 21 October 2019 ). But, at the very last minute—amid breathless media expectation—the picture was a no show.

Only the Ganay version of the Salvator Mundi was included in the Louvre exhibition © Musée du Louvre/Antoine Mongodin

So, what happened? As “Jacques”, the anonymous official, tells us: “The painting went under a number of machines and it was X-rayed all over. Vincent Delieuvin [the chief curator in the department of paintings at the Louvre] brought together all sorts of international specialists, and at the end of the process the verdict was revealed: the scientific evidence was that Leonardo da Vinci only made a contribution to the painting. There was no doubt. And so, we informed the Saudis.”

Chris Dercon then takes up the story. President of the Association of French National Museums-Grand Palais since 2019, and currently a board member of the Visual Arts and Museums Commissions of the Ministry of Culture of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, Dercon has worked closely with the Saudis for many years, and, in his own words, “opened doors”. He jokingly describes himself in the film as a “mercenary”. He was there in the office of the Louvre’s president-director Jean-Luc Martinez “when a delegation of Saudis close to the ministry of culture came to hear everything Jean-Luc Martinez had to say. It was very brave of the Louvre to say, ‘this is what we think, many others may think differently, but this is what we think as a scientific reflection on the painting’. I trust the director of the Louvre, I follow the scientists, it’s not for me to say. I have confidence in the Louvre, it’s a question of confidence, the director of the Louvre decides where the painting is going to be shown and in what context.”

Unsurprisingly, when this was communicated to the Saudi officials, they were not happy. “Jacques” proceeds to tell Viktine: “The whole thing changed in a way that was incomprehensible. MBS laid down very clear conditions—show the Salvator Mundi beside the Mona Lisa without any other explanation, present it as 100% Leonardo da Vinci. There were all sorts of negotiations; Saudi Arabia promised a fund or something, but even on Al-Ula they were bad payers, so it wasn’t very rational.”

Now, as the film relates, the French foreign affairs minister, Jean-Yves Le Drian, and the culture minister Frank Riester, weighed in, lobbying on behalf of the Saudi request. In the meantime, prior to the exhibition opening, a Louvre official told The Art Newspaper that two versions of the catalogue had been produced: one to be used if the picture were to be shown in the exhibition, the other if not. Towards the end of September 2019, Macron made a decision: the Elysée was not going to accept the Saudi conditions. Nevertheless, discussions between French officials and the Louvre continued.

The show opened on 21 October—without the picture. The published catalogue had a missing entry between cats 156 and 158, and the Louvre’s exhaustive technical analysis, according to the film’s voice over, was stowed away as “a state secret”. But, according to Vitkine, Dercon was in Saudi Arabia by the end of the month, telling the Saudis that the Louvre had made an offer, and that the door was still open. Government insurance indemnity was extended, as The Art Newspaper revealed, to allow the picture to arrive late to the exhibition.

Salvator Mundi

And then, as The Art Newspaper also exclusively revealed, there was another new development that is yet to be adequately explained. In December, the Louvre produced a short book devoted to the Salvator Mundi, presenting in detail the conclusions of their laboratory examinations of the picture. And, in the preface, Jean-Luc Martinez pronounces that, “The results of the historical and scientific study presented in this publication allow us to confirm the attribution of the work to Leonardo da Vinci…”. The book’s chapters by Vincent Delieuvin and his colleagues from the research department of C2RMF support the positive attribution to the master. These findings seem to contradict the film’s narrative.

A footnote to the main text of the book (No.1) offers something by way of explanation: “This text completes that of the exhibition catalogue pages 302-323, which remains general due to the absence of the work at the opening of the exhibition. On the occasion of the presentation of the work at the Louvre museum, it was possible for us to make public the results of the analyses which renew the material knowledge of this painting.” The book, which must have been produced with the agreement of the Saudi ministry of culture, was, however, then immediately suppressed by the Louvre, due to the fact that the picture would now definitively not be included in their exhibition. (The museum is not permitted to write about privately-owned works if they are not displayed in their galleries.) The book’s existence is something the Louvre is not willing to discuss. The Louvre was also asked to comment on Viktine’s film, but declined.

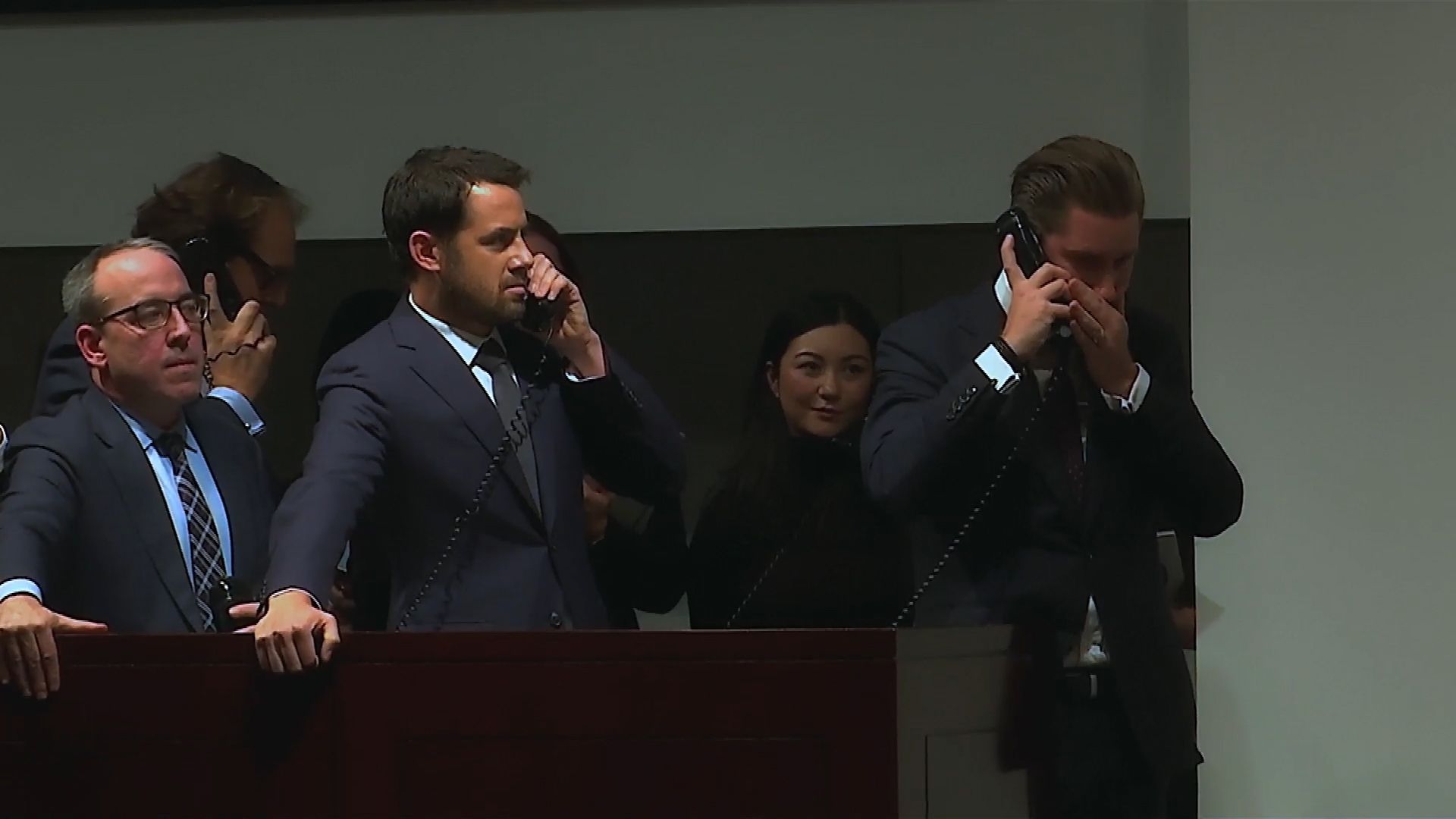

Salvator Mundi sold at Christie's for $450m in 2017 © Zadig productions/FTV

Despite the severe pressures that the Louvre must have been under, Macron’s decision prevailed: “In September 2019”, “Jacques” relates in the film, “President Macron took the decision not to follow MBS’s conditions... Understand, at stake was our credibility, the credibility of France, of the Louvre, over a long period. In the long term we would no longer be lent works if we did this sort of thing … You have to have convictions that go beyond the present.” He adds: “On the French side, there were two positions, Riester who was minister of culture and Le Drian, the minister of foreign affairs. They were interested in all the projects that the Saudis were waving in front of us. My position, which I communicated to the highest level, was that the Saudis’ conditions were unreasonable and that exhibiting it on their terms would have been laundering a work at $450m.”

Perhaps the last word on the matter should go to Leonardo expert Martin Kemp, who is also interviewed by Vitkine for the film. Kemp was, of course, one of the most prominent champions of the Salvator Mundi’s attribution to Leonardo da Vinci when it first appeared—following extensive restoration—at a National Gallery, London exhibition in 2011 (attributed solely to Leonardo) and when it was subsequently sold at Christie’s. He says: “What was published in the Christie’s [sale] catalogue was overly definite, absolutely.” And he tells Vitkine. “I wouldn’t stick my neck out unless I was reasonably confident, but you can always be wrong. If I’m wrong, nobody died—somebody lost a lot of money ...’

• Antoine Vitkine’s film Savior For Sale will be broadcast on French Television’s France 5 on 13 April