What is it?

The Art Newspaper's XR Panel has spent the global pandemic viewing work remotely and virtually. Here we review the year and highlight some of our favourite, and least favourite, XR experiences. With works by: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Sol LeWitt, bitforms galleryand others.

The XR panel was launched by The Art Newspaper in July 2020 in response to a growing need to consider XR art as an interconnected review of the art and technology. It is produced by Louis Jebb and curated by Gretchen Andrew. All reviews in this series can be found here.

Highest rated (4.5 stars)

A reference point for the art world: the Sol LeWitt estate, Lindsay Aveilhé and Microsoft created a richly immersive, interactive app

Lowest rated (3 stars)

Wunderkammer by Olafur Eliasson with Acute Art

The year in review

XR shouldn’t be viewed as having the solve-all solution—rather a complex kaleidoscope of multifaceted possibilities outweighed by ethical and cultural obligations.Valeria Facchin

Valeria Facchin: The global crisis has accelerated the necessity to replicate and expand our confined reality, yet it seems that the art world is still struggling to understand the full potential of XR. Through the digital we can explore a new sense of space, a new extension. This year, the XR Panel highlighted the vast spectrum of possibilities offered by these media: their taxonomisation is therefore essential to understanding the multiplicity and complexity that each architectural choice unfolds. Yet, while looking back at each project, I asked myself: “In this constant shift between pluralities, what is the conceptual and ethical meaning conveyed to the public when digitally translating?"

How to avoid the risk of cultural appropriation?

To begin answering this question, I will begin by looking at two projects produced by the Metropolitan Museum of Art and reviewed by the panel: The Met Unframed and the AR transposition of the Zemí Cohoba Stand.

The Met Unframed allowed one to enter the museum spaces and play around with some of the collection display for a limited time. This approach was successful in two ways. First, by pre-setting the time one could spend on the app, this forced a need to experience the works in the "real space". Secondly, by adding a gaming-like experience, people were able to become curators, understanding the value of visual connections, and consequential ethical, cultural and historical implications, when exhibiting works.

Amazingly designed: the Zemí Cohoba Stand Public domain/courtesy of Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

The approach differs greatly for the amazingly designed AR replica of the Zemí Cohoba Stand (from the Dominican Republic, around AD 1000). A ritualistic object, the zemí was used as a base for community ceremonies involving the consumption of hallucinogenic substances. While the additional available content offered some insight, such as for the 3D modelling process, the curatorial statement aroused some concerns. How could the beauty of the Zemí Cohoba help relieve collective grief? Materiality is as important as the functionality for which an object was conceived, in this case for the use of drugs as part of a spiritual experience. By miscommunicating this, a threat of neo-colonialist and cultural appropriation seems to arise. This issue is critical especially in times where there is a prerequisite for institutions to act upon decolonisation. This could be avoided by going beyond the visual element, and consider the complex interaction of the object with its surroundings. Digital replicas should therefore be considered as a way to access this additional layer of information, evoking the meaning—the essence—of that specific object, which is far more powerful than the merely visual and material identity.

Complex interaction of the object with its surroundings: the Zemí Cohoba stand as an AR object

When thinking of this, I have two examples in mind: the exhibition Touching Masterpieces (2018), at the National Gallery in Prague, and Juliet’s balcony in Verona. The first offered some valuable considerations in terms of museum accessibility and multi-sensory experience. For the occasion, Michelangelo’s David, the bust of Nefertiti, and the Venus de Milo were transformed into virtual objects which people could "see" through haptic glove technology for the first time. The latter is interesting when considering what the public perceives as "the original". A historical falso, the balcony is, in reality, a horses’ trough, yet its aura and "concept", still reverberates and attracts millions of visitors a year.

As the work of art in the age of digital reproduction can be replicated several times without a degradation in quality from the original, it is important for museums to focus on their educational approach. The information and the cultural references an object conveys is where its uniqueness and aura lies.

Ubiquitousness and Geolocation: two sides of the same coin

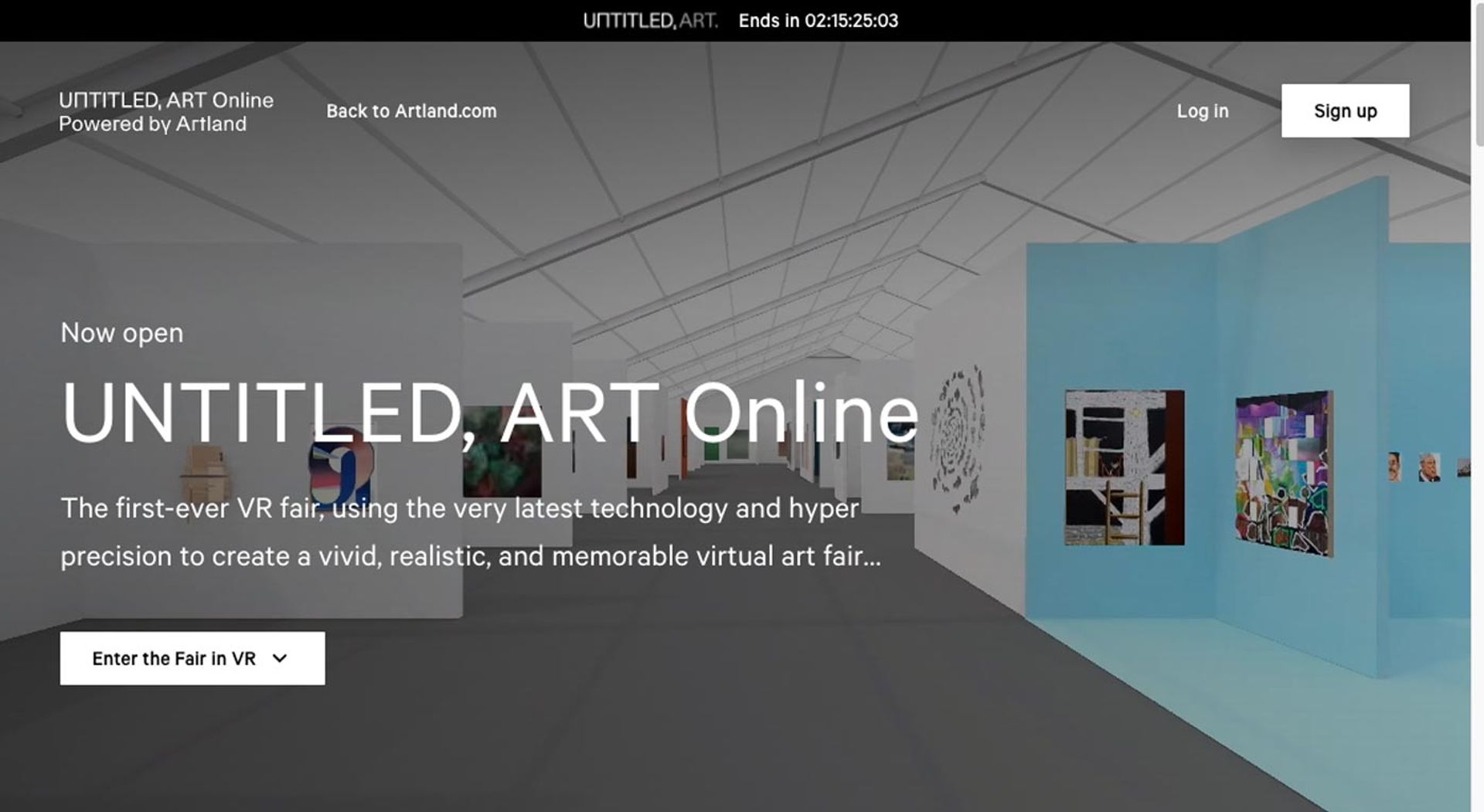

If there is one thing that the pandemic brought to our attention it is how unsustainable the art system is. Digital platforms not only increase the accessibility of the work and its dissemination by removing how "ownership" is traditionally held. This has opened up conversations and interesting solutions when discussing their impact on climate emergencies. By moving some of the events online, as done by Untitled and Vortic Collect, new attention and solutions around the art world’s carbon footprint, have been discovered.

Untitled, the Miami art fair, was fully virtual in July-August 2020 through a web-based VR experience built by the Artland platform

The London Collective, of leading UK galleries, formed during the first wave of the global pandemic, is virtually live again on Vortic Collect after finding a home there in June 2020 when the Vortic platform was new

It’s interesting however to notice how XR is contemporarily ubiquitous, by being both accessible worldwide, as well as limited by geolocation. Being familiar with Daniel Birnbaum (the curator and director of Acute Art) and his ideas of ecological emergency, I was able to recognise some of these approaches in the projects lately realised. An example of this approach is offered by Acute Art’s Unreal City, where 36 AR sculptures—by Nina Chanel Abney, Olafur Eliasson, Cao Fei, Alicja Kwade, among others—were arranged as a walking tour along the River Thames, in London. By limiting the experience to specific geolocation, like Koo Jeong’s A Density (2019), which was accessible only in Regent’s Park, Acute Art is helping AR art to become valuable to collectors and museums. In other words, if the work is available only in one place, no one else has it. In that way, they are introducing a kind of attractive limitation that makes it collectible.

Immersive virtualities

By representing a layered extension of the physical realm, virtual environments could be compared to mini-ecosystems or mesocosms, enclosed and essentially self-sufficient controlled experimental environments where cultural concepts such as body fluidity can be reimagined. Presented by bitforms gallery, and curated by the tech-savvy Zaiba Jabbar and Valerie Amend, the exhibition Disembodied Behaviors—which included works by Julie Béna, Vitória Cribb, Kumbirai Makumbe, LaJuné McMillian, and Alicia Mersy—is a perfect example of how complex conversations can be productively delivered in the digital sphere. By celebrating the potential of "digital individuals, who range from avatars imbued with cultural memory to AI narrators, to dismantle predictive structures of power" the exhibition, hosted on New Art City, a multi-user online platform to experience digital art, reflected on the liberating feeling that one can experience in the digital world.

Yet, the exhibition aroused some important questions relating to the function and limitations of one’s virtual body which made me think to Katherine Hayles writing, in 1999: “ If my nightmare is a culture inhabited by posthumans who regard their bodies as fashion accessories rather than the ground of being, my dream is a version of the posthuman that embraces the possibilities of information technologies without being seduced by fantasies of unlimited power and disembodied immortality". (Katherine H. Hayles, How We Became Posthuman, University of Chicago Press, 1999. )

Perhaps we should start from here—discussing the ethics of XR. While the virtual realm offers opportunities for the reconceptualisation of culturally-rooted stereotypes, we should never lose sight of its interdependency with the physical world. XR shouldn’t be viewed as having the solve-all solution—rather a complex kaleidoscope of multifaceted possibilities outweighed by ethical and cultural obligations.

The XR Panel's highest-rated experiences

Standouts—the sumptuous spatial structuring of Substrata, and the refracting ultraworlds of Disembodied BehaviorsEron Rauch

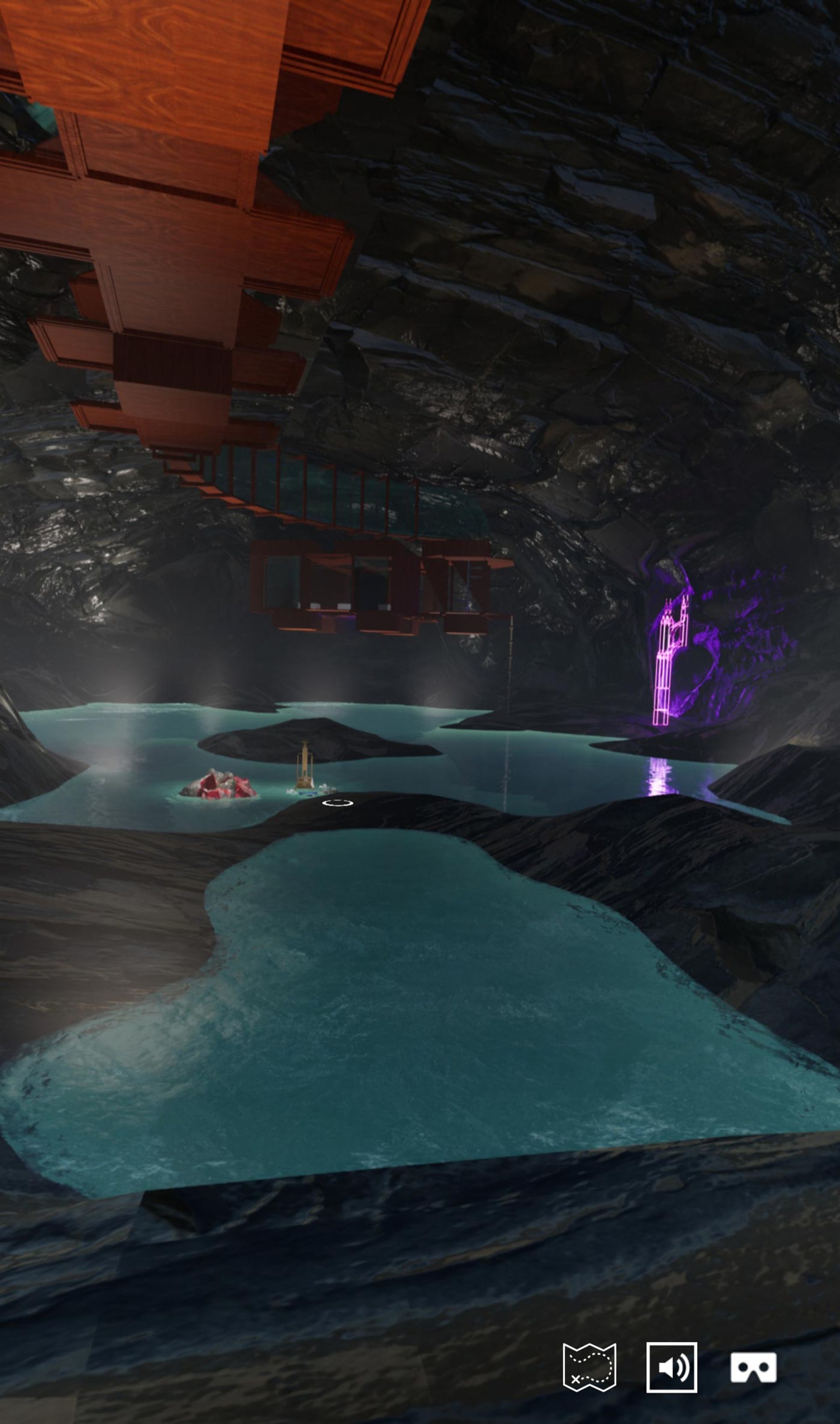

Sumptuous spatial structuring: Epoch Gallery's Substrata

Carole Chainon: My favourite immersive art experience was Epoch Gallery’s Substrata for maximising its use of the virtual space, taking us out of the traditional art gallery format and incorporating artworks in different digital formats. It was a memorable journey. Disembodied Behaviors and the Sol LeWitt Estate app came close seconds.

Dhiren Dasu: Sol LeWitt & Microsoft, curated by Lindsay Aveilhé. The virtual show was so successful since it allowed one to experience LeWitt’s work in novel ways. The aesthetic of the implementation is clean and accurately reflects the artist’s oeuvre.

Eron Rauch: I predicted that, as the year went on, we’d finally see examples of the next generation of fully-realised 3D art shows that engaged with their medium in deeper ways and pushed technical sophistication beyond previous bounds. And we got those shows in standouts—the sumptuous spatial structuring of Substrata, and the refracting ultraworlds of Disembodied Behaviors.

The XR Panel's lowest-rated experiences

Carole Chainon: It is hard for me to pick "the worst" because there is value to be found in the experimentation of each of these virtual art experiences, but Kiki Smith’s I Am a Wanderer virtual tour seemed less engaging due to the inability to get close to the artworks and its traditional 360 tour format.

Dhiren Dasu: Black Lives Matter murals in Los Angeles, published in AR by the Los Angeles Times and Yahoo. The actual implementation left a lot to be desired. The fact that it was limited to the newest IOS devices is problematic since it eliminates so many users.

Eron Rauch: Since I handed out a tie for best, I’ll also give a tie for the two worst moments: Acute Art’s Wunderkammer pushing in-app microtransactions like the Fortnite store; and Oxford Modern Art’s Kiki Smith show’s boggling attempt to reinvent the completely-solved-for-three-decades 3D keyboard movement scheme by hard-mapping WASD to the virtual West, North, South, and East of the gallery.

What did a year of lock down mean for the medium of XR?

The lack of physical art shows really highlighted the need for the art world to democratise the experience of viewing work. It is no coincidence that the Zeitgeist is obsessed with blockchain and non-fungible tokensDhiren Dasu

Carole Chainon: The pandemic and confinement propelled the use of XR. After years of debating whether XR was a gimmick and public perception about whether it was going to suffer the same fate as 3D TVs, the answer is a clear "No". XR is a full-bodied technology heading to the mainstream and its value is now uncontested, especially when people can make use of their mobile phones or increasingly accessible XR hardware. Whether 360 virtual tours, AR 3D placement, AR portals, or full VR tours, art institutions and galleries are well aware they can no longer ignore the trend and should adequately provide an XR offering for their patrons. Art is a means to express and share with the world, and XR allows for exactly that.

Dhiren Dasu: 2020 qualifies as the annus horribilis of our era in so many ways, but for the XR world, it was a moment of opportunity. The lack of physical art shows really highlighted the need for the art world to democratise the experience of viewing work. It is no coincidence that the Zeitgeist is obsessed with blockchain and non-fungible tokens. This crypto revolution is fundamentally about information being stored non locally. Art can benefit greatly from being untethered to a physical location. This is the moment that XR can come into its own as a legitimate “venue” for artists, collectors, and viewers.

Eron Rauch: Reflecting on the year, I was surprised at how I increasingly veered away from simulations of pre-existing things from the plagued-yonder. Yes, in my most exhausted moments, a stroll through photo-documentation of a museum show or a surf movie was a pleasant default purgatory. But as evidenced by my picks for best shows of the year, what most nourished me and reinvigorated my creativity were novel experiences that owned and explored their own rich circumstance of existence, whether that was an intimate artist book or an intricately realised VR world where art and space entangle.

What did you see change this year that excites you?

Social XR ... will make XR art the more enticing when shared with othersCarole Chainon

Carole Chainon: I am very fond of experiences that make the most of XR capabilities and take us on a journey outside the traditional gallery or museum format, while giving us a behind-the-scenes glimpse into the mind of the artist. Artists get more control in the way their work is experienced, and can shape the creative context in which their art will be experienced. Another noteworthy and exciting trend is the use of social XR, which we’ve seldom encountered in our reviewed experiences, but this social layer will make XR art the more enticing when shared with others. Overall, the surge in virtual exhibits and user adoption has been an exciting change in itself.

Dhiren Dasu: The rise of digital art and the blockchain based authentication and sales systems allow for a wider exchange of art that is accessible to all people. XR is a critical component in creating this new system of experiential art.

Eron Rauch: While some of the specific shows were fantastic, the most exciting part of this rapid evolution of XR art tech is exemplified in what we were given by Epoch and New Art City: rich platforms, technical tools, and critical ideas opened up for diverse curators and artists to join making and exploring these hybrid art shows in the virtual era. Even the more standard professional and DIY XR platforms deserve shoutouts for the access they offer!

Were you disappointed at anything that did not change?

Looking through the coverage in most major art publications, you would hardly know video games even exist—in a society where more than half the population engages with them—let alone that there are thousands of artists making incredible, sophisticated, and experimental worksEron Rauch

Carole Chainon: I hope we’ll see more emerging artists being highlighted in the art XR space, and that artists and institutions will keep pushing the medium beyond our traditional conceptions of the gallery and physical space where artworks are showcased. XR will pave the way towards introducing new emerging artists, and emerging media, to an ever wider range of users from all walks of life.

Dhiren Dasu: A standardised approach and implementation XR experiences is still lacking. The XR space needs quality controls to give viewers more than they would experience with a physical show. Capture and display systems for fine art need to be high resolution. The medium is so full of potential that has yet to be manifest.

Eron Rauch: With all of the hype about XR art shows, it is infuriating to see the continuation of the art world’s abysmally infrequent and oft shallow engagement with video games and game-related projects. Looking through the coverage in most major art publications, you would hardly know video games even exist (in a society where more than half the population engages with them), let alone that there are thousands of artists making incredible, sophisticated, and experimental works and as equally many scholars and critics producing critically rich texts on the medium. Future art historians will look back at art publications’ coverage of video games from the first decades of the 2000s the same way we do at early 1900s art texts that excluded Modernist artworks and theories. This lack of critical engagement will change soon, but social distancing made me even more impatient for it.

The Art Newspaper’s XR Panel

Valeria Facchin is a curator, producer and researcher. With a focus on visual studies, biology and AI, her work explores the relationship between bodies, technologies and future ecosystems. She is currently working as Assistant Curator & Project Manager at Fiorucci Art Trust, London. Together with Indrani Saha and Delanie Joy Linden, she is the founder of W21, Women 21st Century, a data-feminist participatory research platform focusing on post-feminism and intersectional practice in art, science, culture, and technology.

Gretchen Andrew uses her vision boards to hack systems of power with art, glitter and code. Her next exhibition is with Annka Kultys in April 2021.

Carole Chainon is the co-founder of JYC, a XR development and production studio based in LA with a presence in Europe, creating XR experiences for the entertainment and enterprise sector. She is also a Spark AR Creator.

Dhiren Dasu is a digital media creator and consultant. His areas of speciality include photography, film, virtual space, graphic design, visual effects, animation, and audio production. Dasu, in his fine art persona as Shapeshifter7, makes artworks that echo and recompose the architectural spaces he photographs, turning them into immersive spaces while exploring the nexus of photography, collage, symbols, and perception.

Seol Park bridges technology, art, and branding. After working with Microsoft and INTEL, she now guides global branding at LG with emphasis on digital and cultural engagement. Her work in XR has appeared in Media-N, ABC TV (Australia), The Southern Star (Ireland), and more. She was named in Sotheby's Institute's "4 Under 40" in 2019, and currently serves on the Board of Trustees for The American Folk Art Museum.

Eron Rauch is an artist, writer, and curator whose projects explore the infrastructure of imagination, with a focus on subcultures, video games, and photography history. He is the founder of the website Video Games for the Arts, writes for the video game industry, and teaches photography at CalArts. His photo book about virtual Tokyo, Such is the Power of the Empty Lot, was published alongside Heterotopias volume 7.