The Outsider art champion and museum founder Ruth DeYoung Kohler II, died on 14 November, aged 79, at her home in Wisconsin. From 1972 to 2016, Kohler served as the director of the John Michael Kohler Arts Center in Sheboygan, and raised its profile internationally as one of the leading institutions dedicated to self-taught and folk artists. She stepped down to focus on her dream project—the Art Preserve, a 56,000 sq. ft museum devoted to artist-built environments that was due to open this summer before the coronavirus pandemic hit. The Art Preserve, which includes visible storage and will also serve as a research center, is now due to open June 2021.

Kohler studied art history at Smith College, then moved to Spain in 1963 where she studied paleolithic cave art. When her father became ill in 1967, she returned home and began volunteering at the Arts Center—then operating out of the mansion that was her grandparent’s former home. In 2000, the Arts Center expanded with a 100,000 square-foot addition. Both the Art Center and the Art Preserve are located near Lake Michigan just east of the town of Kohler, home to the eponymous plumbing manufacturing company started and still run by her family.

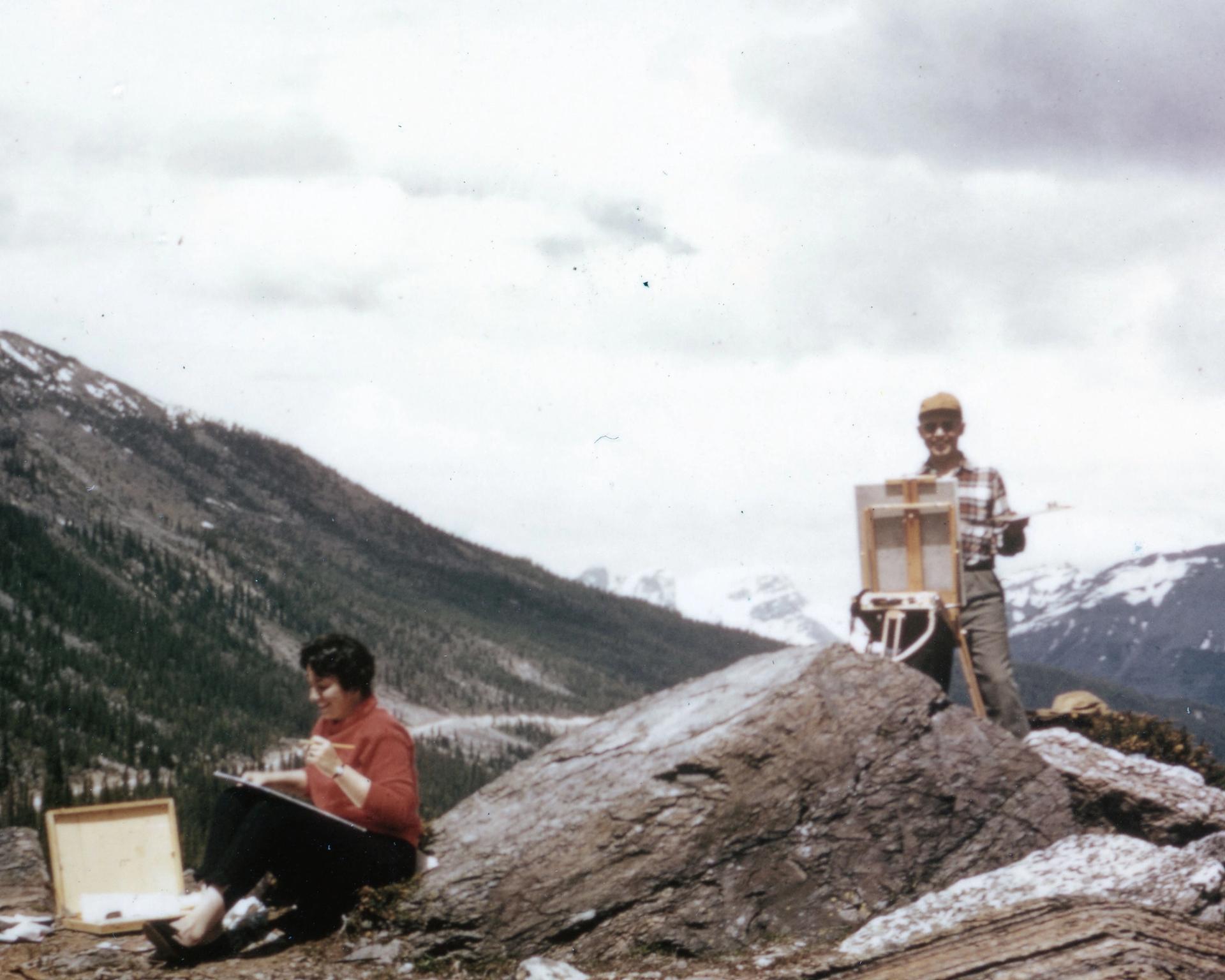

Ruth DeYoung Kohler II painting while attending the Banff School of Fine Arts in 1960

Kohler’s love of artist-built environments started with the Sunday drives her father would take the family on, when he found particular delight in looking for bathtub shrines in people’s front yards. During her early days at the museum, she took a road trip to Wisconsin’s Northwoods to see Fred Smith’s Wisconsin Concrete Park—a sculpture park filled with hundreds of concrete figures adorned with stones and shards of glass—which set her on a mission to rescue and preserve such unique sites.

As a guiding force on the board of the Kohler Foundation, she helped ensure that around 25,000 works by self-taught artists were properly cared for, but until the Art Preserve was built, most of these remained in storage. Among the collection’s treasures are 600 wooded carved animals housed in hinged shadow boxes by Levi Fisher Ames (1843-1923), who travelled around the region displaying his creatures in a tent, and the concrete and fabric figures by Nek Chand (1924-2015), a self-taught artist from India whose Rock Garden is in the foothills of the Himalayas. Fifteen sites in the US, including St EOM's (Eddie Owem Martin) Pasaquan, a seven-acre art environment in Georgia, have also been restored in situ by the foundation.

Fifteen sites in the US, including St EOM's (Eddie Owem Martin) Pasaquan, a seven-acre art environment in Georgia, have been restored in situ by the Kohler Foundation

“Saving art environments is a complex, consuming, and multifaceted endeavour,” says Valérie Rousseau, the senior curator at the American Folk Art Museum in New York, which awarded Kohler its Visionary Award in 2015. “Not only was Ruth Kohler successful in conserving and preserving sites and large-scale installations, through her vision, determination, and generosity, she brought broader recognition to self-taught artists and inspired generations of students, curators, and scholars.”

During her tenure as museum director, Kohler also established the Arts/Industry residency programme, where visual artists work on the Kohler factory production floor in the Pottery and Foundry departments. One early result of this collaboration are the postcard-worthy museum washrooms where the artists, supported by seasoned factory workers, created tiled extravaganzas and specially designed toilet bowls.

Kohler knew how to communicate the value of art to the business side of the family enterprise, says Sam Gappmayer, who became the director of the John Michael Kohler Arts Center in 2016 after Kohler stepped down. And ambitious projects like the Art Preserve, “would not have happened without her,” Gappmayer adds, pointing out that Kohler was involved with the project up to the last weeks of her life, making one last visit in late September. Kohler was also able to see progress on another project that was close to her heart, the preservation of the artist Mary Nohl’s house near Milwaukee.

Kohler devoted the last years of her life to her dream project—the Art Preserve, a 56,000 sq. ft museum for artist-built environments, which was due to open this summer before the coronavirus pandemic hit Courtesy of Tres Birds Workshop

The architect and artist Michael M. Moore, whose Denver-based firm Tres Birds has designed the Art Preserve’s museum building, met Kohler during on a visit to Sheboygan in 2015, when he was working on a public art project sponsored by the Arts Center. During a tour of the museum’s vast underground storage, Moore learned of her plans to create a new home for the extraordinary collection and pitched his firm for the project. “She asked very good questions,” Moore says of their first meeting, and she only had one demand: “That the art be totally protected.”

Kohler’s vision for the Art Preserve was unwavering. With so many fragile pieces in the collection, she was concerned about safely displaying the works while also providing an experience that might approximate how the art would be seen in its original habitat, so the design firm sourced high-tech windows that cut out most of the ultraviolet light while connecting visitors to the outdoors. “For Ruth, the artist and the art was primary,” Moore says.