The arboreal-themed group exhibition Among the Trees at the Hayward Gallery (until 17 May; £14, concessions available) considers how “trees change our sense of time,” says the curator and director, Ralph Rugoff. And indeed, this expansive survey of such ancient, static beings helps to contextualise the fast-paced, ephemeral nature of our own existence. Jennifer Steinkamp's video Blind Eye (2018) shows a grove of animated birch trees gently swaying and sprouting then shedding leaves—an entire year harmoniously compressed into three minutes. Other works more directly examine the relationships between humans and trees, which, in their still vigilance, bear witness to our ugliest behaviour. Violent racism haunts hanging branches in Steve McQueen's Lynching Tree (2015); Roxy Paine's ashen diorama of a burnt forest landscape addresses the urgency of our climate crisis. Where this show works best, however, are in its wise reflections on the essence of trees. In Giussepe Penone 's Tree of 12 Meters (1980-2) two industrially planed pieces of timber have been scraped away at until their organic form is revealed once again. “The tree is a perfect sculpture [...] it memorialises the feats of its own existence in its very form," Penone once wrote. Accordingly, the greatest art is that which can accept, rather than compete with nature's majesty, and marvel at the beauty of these breathtaking (and breath-giving) beings.

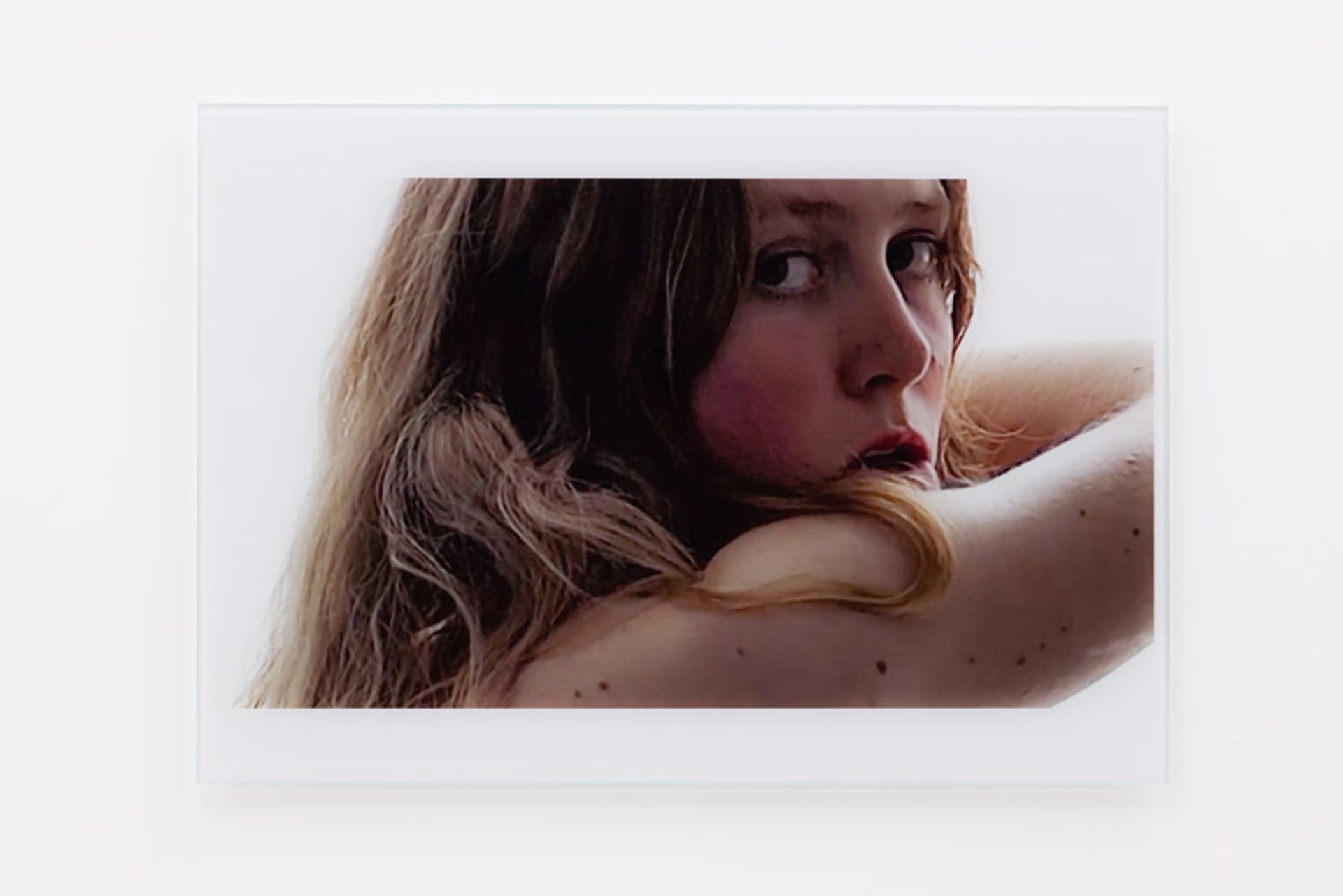

Marie Angeletti's Moira 03 (2020) © Carlos/Ishikawa and the artist

The French artist Marie Angeletti recently placed an ad on Berlin Craigslist seeking women to be photographed nude. She then asked each willing model to masturbate in front of her on film—each one complied. The exhibition Vanessa's at Carlos/Ishikawa (until 4 April; free) is a mixture of Angeletti’s camerawork and pictures the women sent her and edited themselves. Some are erotically charged, while others are decidedly banal. If you're looking for a unifying theme in the content of these photos you might be searching a long time. The real story is in the collaboration that has occurred between the subjects, the artist and the gallerist Vanessa Carlos—an attempt at a more democratised version of the image-making process. But this adroit conversation on authorship and the politics of female representation intentionally complicates itself when placed within a commercial setting. Each of the women have sold their image and were paid €120 for three hours of work. Each photo is now being sold for £4,500. “I chose to call this show Vanessa’s partly because of this co-dependency we all have with one another, as players in a system”, Angeletti says. Pointed but not didactic, this show invites a deeper reflection on the difficult matters around who owns what and what we owe to whom.

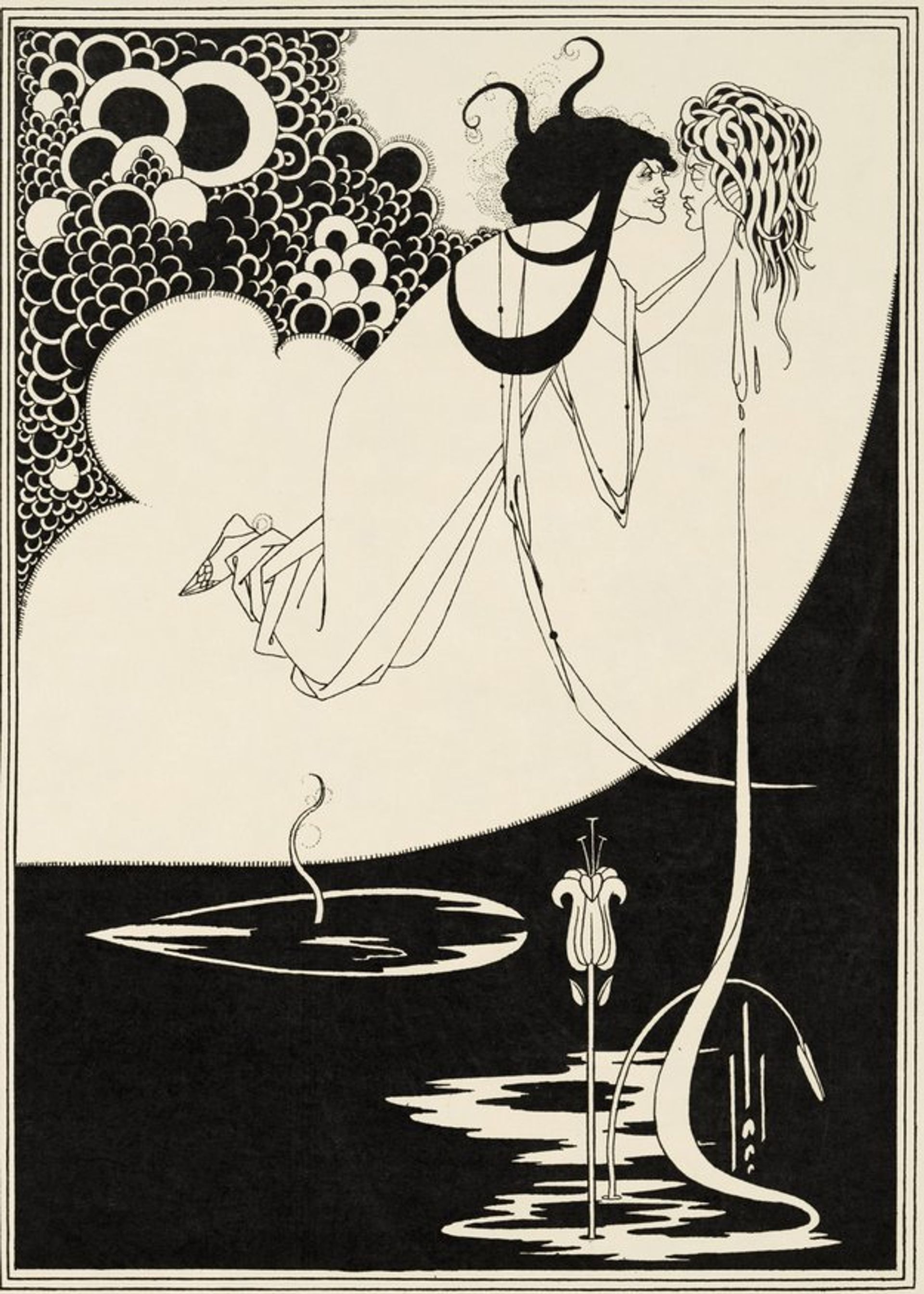

When the Victoria and Albert Museum held an exhibition of works by Aubrey Beardsley in early 1966, a new generation of younger devotees taken with the Victorian artist’s stylish, monochrome illustrations flocked to the London institution. Beardsley died in 1898 aged 25, but his decadent, daring works struck a chord with the rebellious counterculture generation of the 1960s (Klaus Voormann’s psychedelic design for the Beatles album, Revolver (1966), clearly draws upon Beardsley’s practice). This post-war revival in the popularity of his work is explored in the final section of Tate Britain’s sprawling new show (until 25 May; tickets £18, concessions available), which includes more than 200 works produced in just under seven years. The subversive aspect of Beardsley’s art underpins the entire exhibition, from his racy illustrations for Oscar Wilde’s controversial play Salomé (1893) to his erotic, absurd designs for the ancient Greek comedy Lysistrata by Aristophanes (a series highlight is The Toilet of Lampito, 1896, which shows Cupid powdering Lampito’s ample bottom). Beardsley’s only known paintings, Caprice and Masked Woman with a White Mouse (around 1894)—made on the front and back of the same canvas—are displayed for the first time.