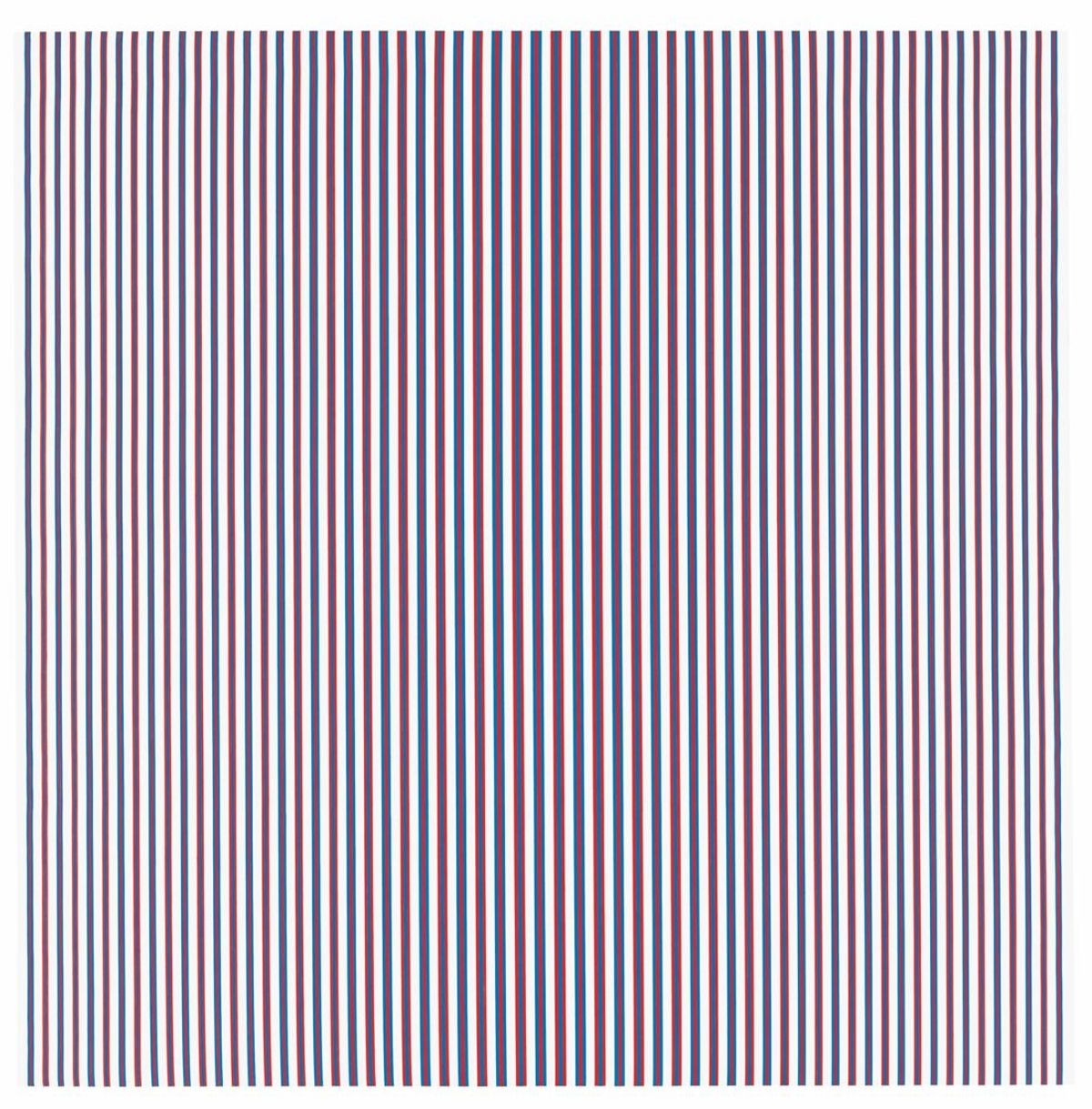

There is more to Bridget Riley’s art than meets the eye (so to speak). The queen of Op Art is known for her abstract paintings which swirl and sweep before the viewer, immersing spectators in lines, curves and spots. This insightful thematic survey of the artist's work at the Hayward Gallery (until 26 January 2020; £18, concessions available) spans Riley's working life, displaying more than 200 pieces dating from 1947 to 2019. The Hayward's senior curator Cliff Lauson neatly bookends her career, highlighting paintings and drawings made before Riley moved into abstraction as well as more recent developments such as her experiments with colour (last year, Riley added turquoise to her palette for the discs series). Deep diving into the trippy black-and-white paintings of the 1960s such as Movement in Squares (1961), and Tremor, (1962), is certainly recommended. Here you'll find hidden gems like the 1961 work Kiss, which shows two vast slabs of black paint on the point of embrace.

Fresh on the heels of announcing their representation of Eduardo Paolozzi's estate, Hazlitt Holland Hibbert are showing a selection of works by the 'godfather of Pop Art' with Hollow Gods (until 17 December; free). Paolozzi is well known for his large-scale sculptures and to millions of rushing Londoners for a mural in Tottenham Court Road tube station. This show, which focuses on smaller-scale works made in the first 15 years of his career, provides a new and welcome insight into the British artist. A particular highlight is the human-sized St Sebastian IV (1957), whose surface rewards an up-close look. There is something mesmerising about Paolozzi's mish-mash of industrial scrap and clay encased in bronze, aptly likened to "encrusted larvae" by the art historian Herbert Read. The shadow of the Second World War hangs heavy over this show. Its title pertains to those Paolozzi gave his own works, each named after a deity and refers to a certain emptiness felt in the post-war era, that of “the irony of man and hero, the hollow god".

Mark Bradford has titled his exhibition at Hauser & Wirth Cerberus (until 21 December; free), using the mythical three-headed guard dog to address the horrors of "modern-day gatekeeping and xenophobia". The nine huge paintings (the titular Cerberus is more than 13 metres wide) and the video that accompanies them were inspired by the Watts Rebellion in Los Angeles in 1965, a seminal moment in the US civil rights story. Using his trademark layers of paper and washes of paint, Bradford plays on a mapped analysis of the riots commissioned by the California governor, interested in “the way that [the commission] delineated data." For the exhibition's video work, Bradford looks at a vintage film of Martha and the Vandellas performing their hit Dancing in the Streets, released the year before the riots, which was both a Motown classic and a call to arms for people who protested. Bradford drove around the Watts area, projecting the footage onto the buildings that stand there today. "Everything that I understood about 1965 was through my mother," says Bradford, "so it still, to this very day, has this fabric of myth. And that's why I use that that song.”