The US artist Keith Haring’s drawings of crawling babies and flying saucers, which have seeped into the public consciousness since the artist’s death in 1990, were daubed more than 30 years ago across a very public canvas—the city of New York. How Haring transformed the streets and subways of Manhattan is explored in an exhibition dedicated to the late graffiti pioneer that opens at Tate Liverpool this week.

“In 1978, Haring moved [from Pittsburgh] to New York where his practice developed further. The city was run down, rates were low and a vibrant art community sprung up,” says Tamar Hemmes, the exhibition co-curator. “Many artists eschewed traditional art spaces and turned to the street.” In the late 1970s, Haring studied at the School of Visual Arts by day. By night, he was a regular on the New York club scene, hanging out at venues such as Club 57 with fellow artists including Jean-Michel Basquiat, Kenny Scharf and Andy Warhol.

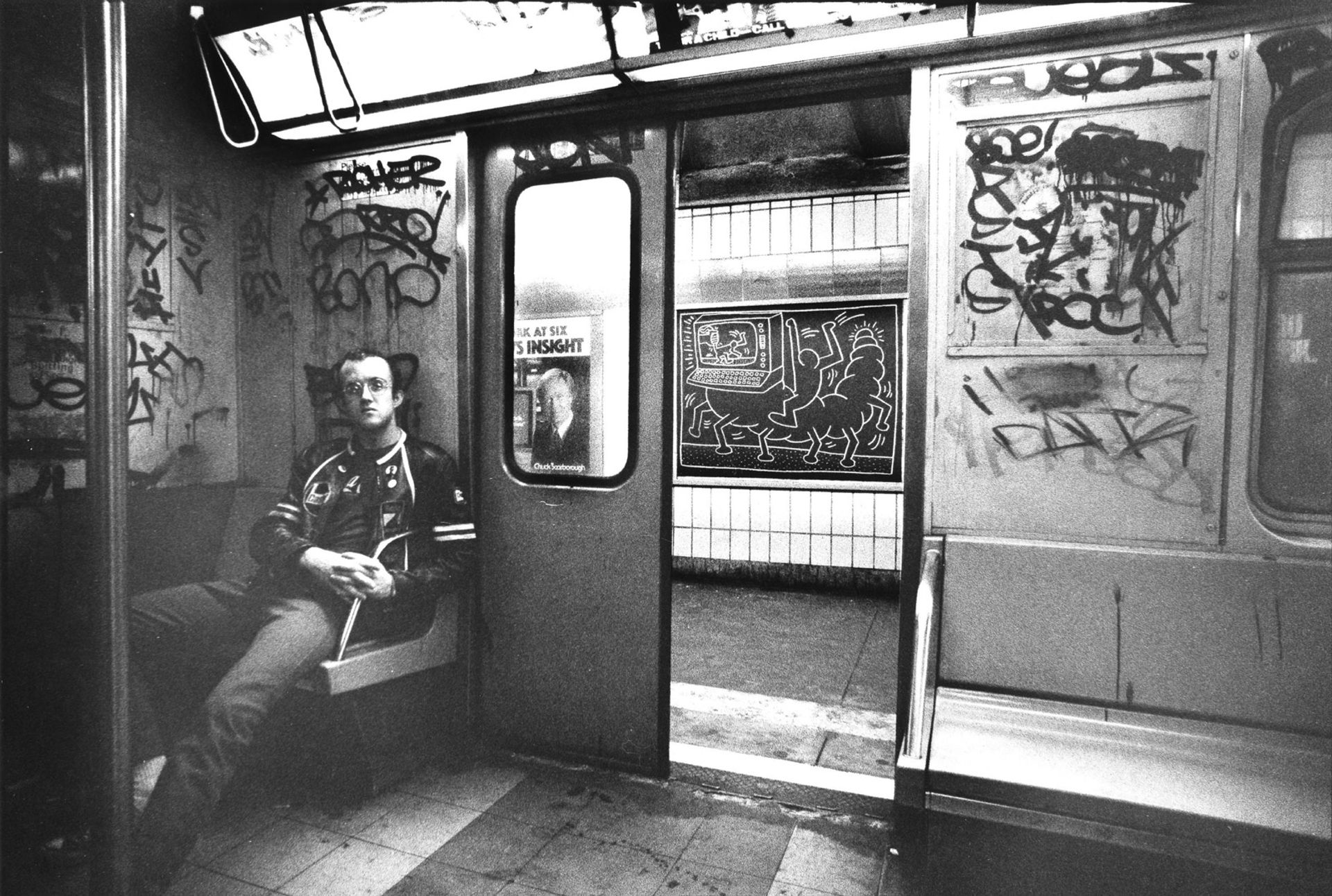

Haring retreated underground, daubing the walls and platforms of the New York subway with his cartoonish figures. Creating art on the metro system was, for the artist, a way of making art as accessible as possible (“Art is for everybody,” Haring said). In the Tate Liverpool show, there are three subway drawings (1983-85) along with a photograph of Haring by Tseng Kwong Chi on the subway in 1983 showing him sat in a train carriage in front of a drawing daubed on the station wall.

Tseng Kwong Chi’s 1983 photograph shows Keith Haring on the New York subway © Muna Tseng Dance Projects, Inc; Art

Other significant works in the show include two hoardings from the early 1980s, one a “totem” piece adorned with smiley faces and a second emblazoned with an image of Mickey Mouse. “In relation to the New York streets, we will also have a taxi hood from a yellow cab, which has been tagged and drawn on by Haring and the graffiti artist LA II,” Hemmes says.

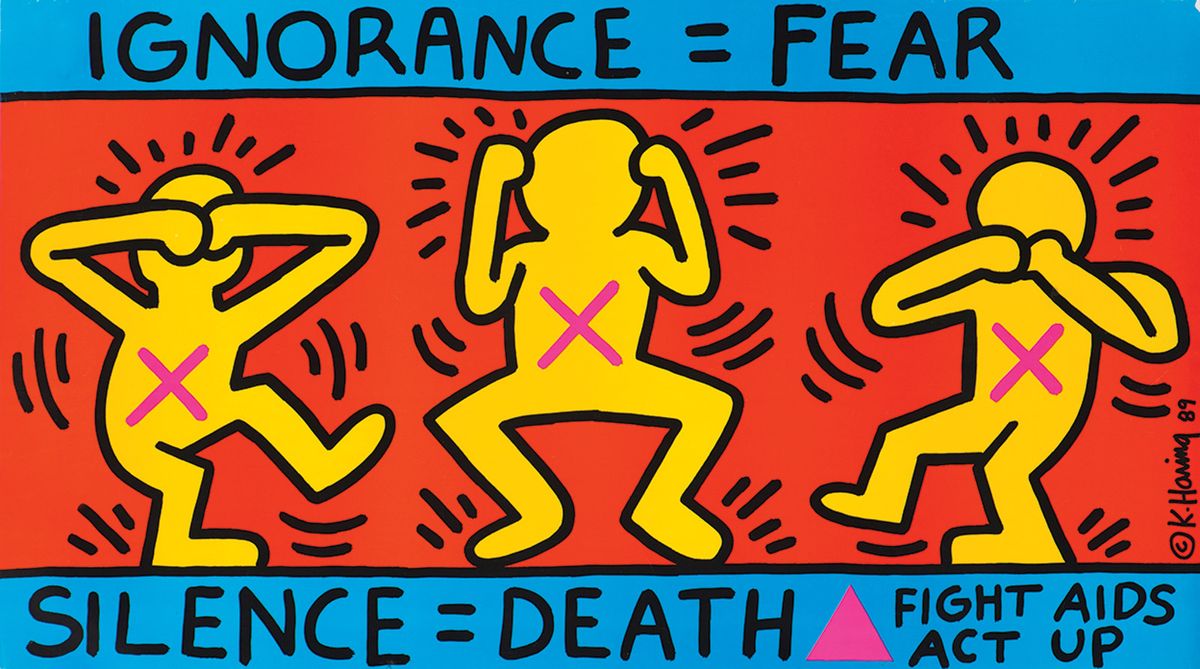

Another staple of Haring’s guerrilla practice was the series of provocative newspaper collages made from copies of the New York Post. The collage headlines, such as “Reagan’s Death Cops Hunt Pope” and “Reagan Slain by Hero Cop”, reflected Haring’s anger and frustration with President Ronald Reagan. Haring’s criticism of the US leader’s refusal to address the Aids crisis can be seen in his Silence = Death work of 1989.

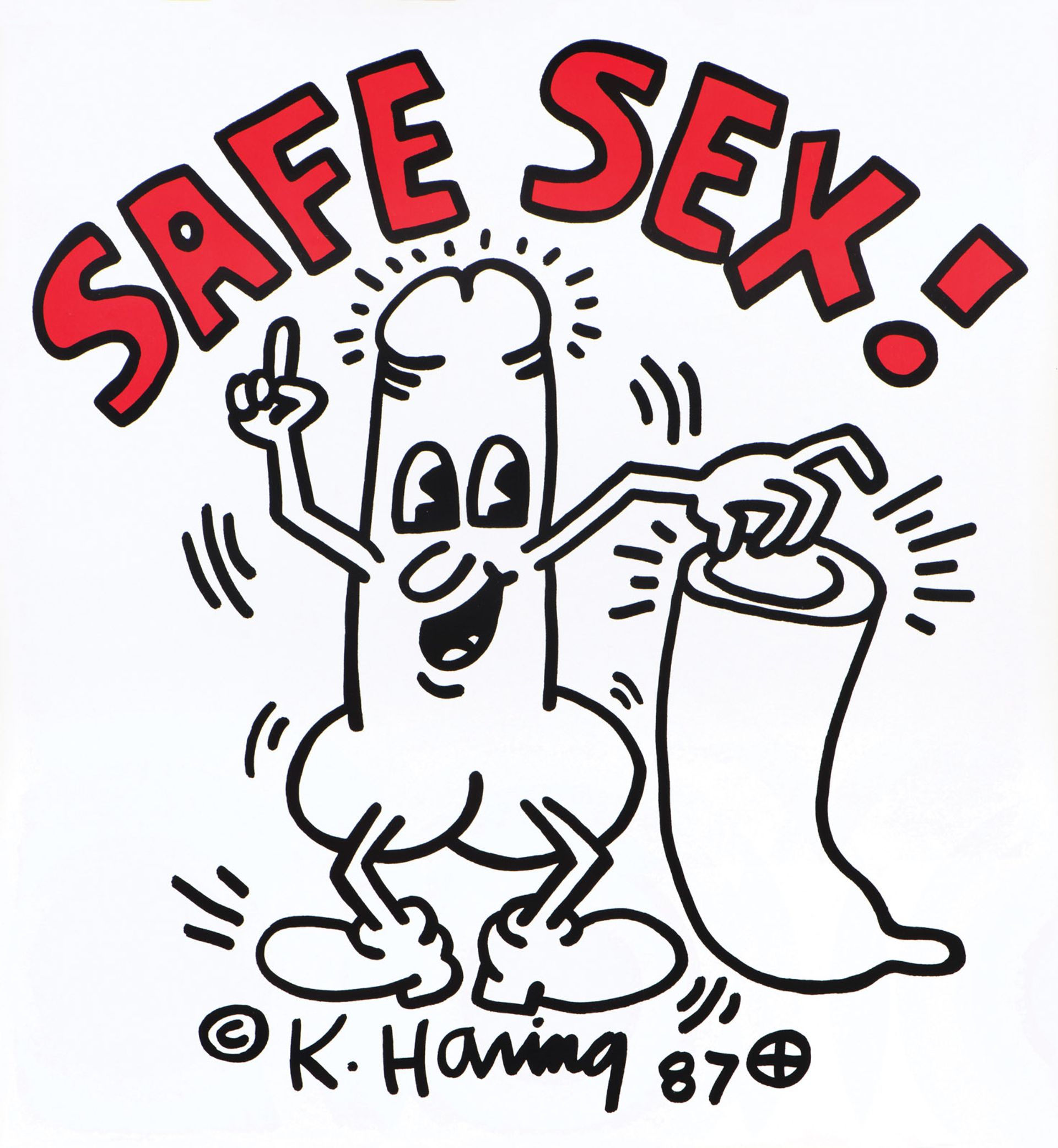

Keith Haring's Safe Sex (1987) © Keith Haring Foundation

“For the newspaper collages, we will have fly-posted copies of the originals, since this is how Haring presented them on the streets,” Hemmes says.

The show is also an opportunity to see photographs of Haring’s public art pieces that still exist today in offbeat, hidden spaces of New York. His Crack Is Wack mural, one of his most famous public art pieces, was unveiled in Harlem River Drive in 1986. The work, a reminder of the crack cocaine crisis that engulfed New York, is currently enclosed by a protective shelter.

Meanwhile, the famed mural in the second-floor men’s bathroom at the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual & Transgender Community Center on West 13th Street—entitled Once Upon A Time (1989)—shows a series of buff male bodies endowed with gargantuan squirting penises.

The exhibition is supported by Liverpool John Moores University, among others.

• Keith Haring, Tate Liverpool, Liverpool, 14 June-10 November