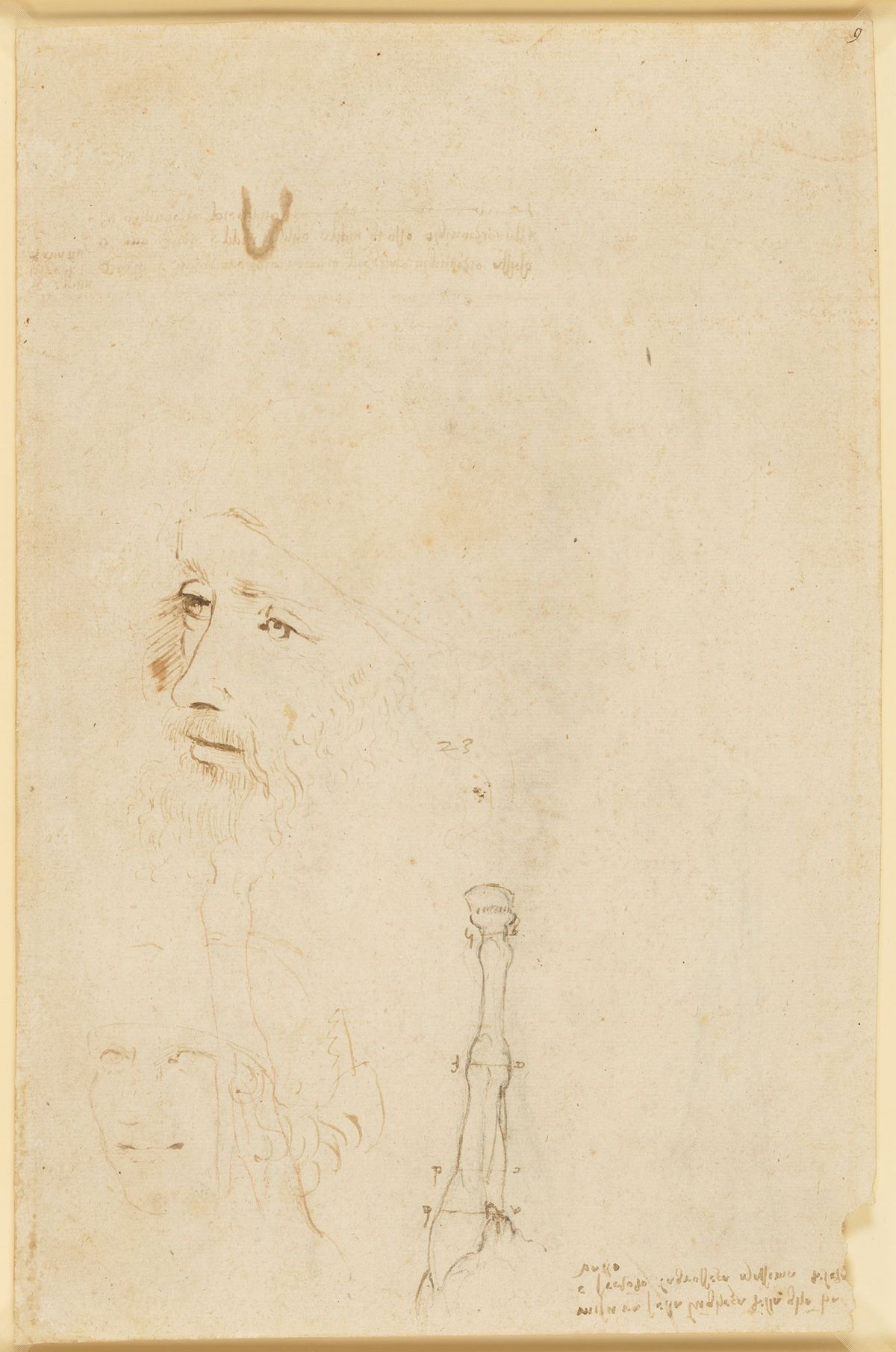

A sketch of a bearded man lost in thought, preserved for 500 years among the papers of Leonardo da Vinci, has now been identified as a rare portrait of the Renaissance master himself. Found on one of hundreds of sheets of Leonardo drawings held in Britain’s Royal Collection since the reign of Charles II, the ink head is believed to be only the second likeness of Leonardo to survive from his lifetime.

The portrait will be displayed for the first time later this month, in an exhibition of 200 drawings from the Royal Collection at the Queen’s Gallery at Buckingham Palace in London. Organised to mark the 500th anniversary of Leonardo’s death on 2 May 1519, Leonardo da Vinci: a Life in Drawing (24 May-13 October) will be the biggest show of the artist’s work in more than 65 years. It follows a dozen smaller displays of Leonardo drawings at venues across the UK, which are due to close on 6 May.

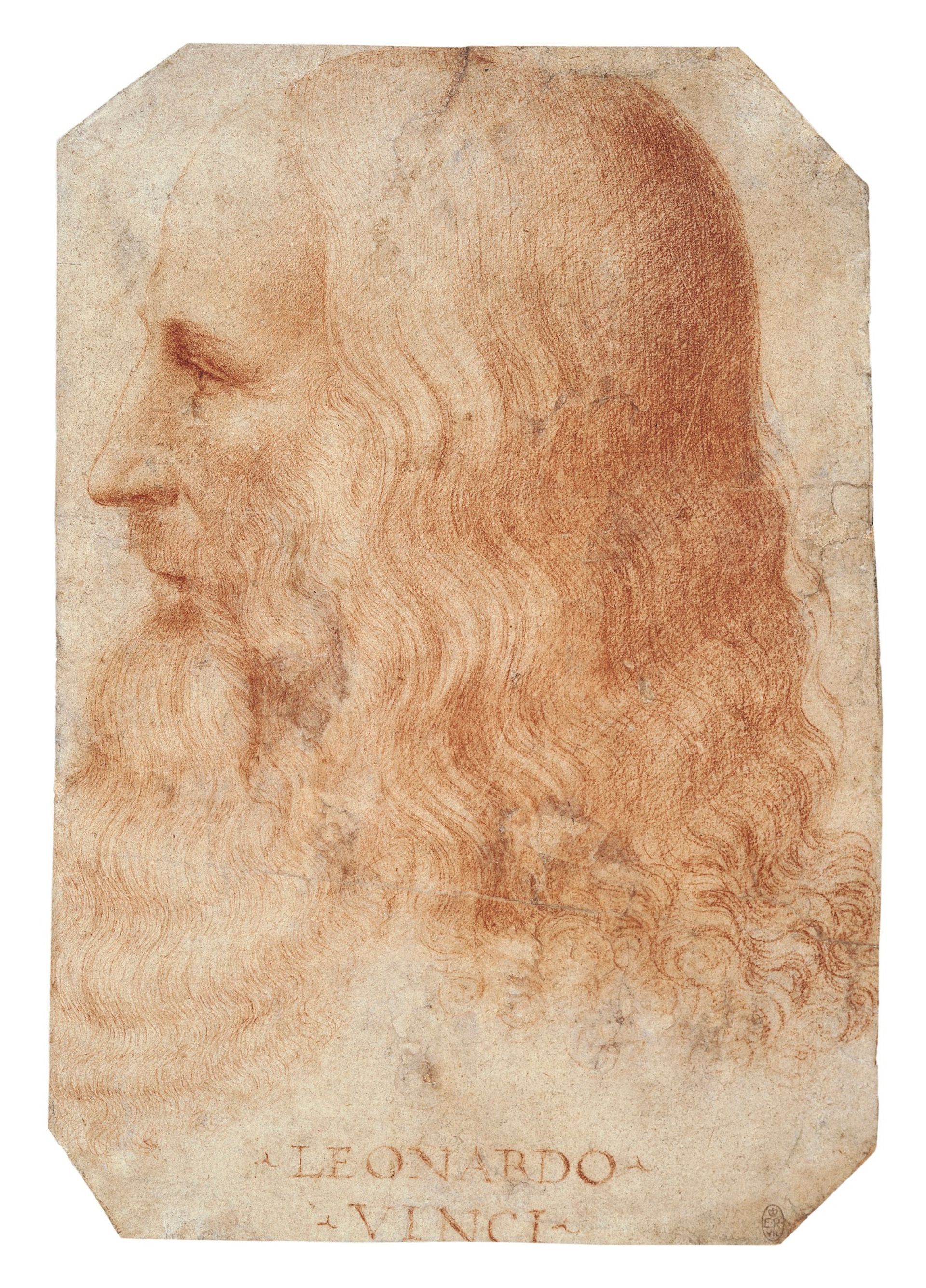

Visitors to the Queen’s Gallery will have the opportunity to compare the sketch, which is dated to 1517-18, with the formal red chalk portrait of Leonardo made by his loyal assistant Francesco Melzi around 1515-18. Seen together, “it is hard to avoid the conclusion that [the ink portrait] is also an image of Leonardo, sketched rapidly by a pupil while Leonardo was in France in the last couple of years of his life”, says Martin Clayton, the head of prints and drawings at the Royal Collection Trust.

A portrait of Leonardo attributed to Francesco Melzi (around 1515-18) Royal Collection Trust / © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2019

Clayton, who reappraised the sketch during his research for the exhibition, points out that the two heads share the same straight nose and flowing beard—an unusual style for early 16th-century Italy. The features chime with early biographers’ accounts of Leonardo as a handsome and elegant figure. Like the Melzi portrait, the ink head has the faraway gaze of an ancient philosopher or seer, “an image that Leonardo cultivated”, Clayton says.

Yet the sketch has long been overlooked, appearing on a double-sided sheet of rough paper that also contains Leonardo’s studies of a horse’s leg and a head of a young man, presumably drawn by the same assistant. The sheet has only been reproduced twice in the past 50 years, Clayton says, and scholars have historically paid more attention to the equestrian studies on it. Kenneth Clark, writing in his 1935 catalogue of Leonardo’s drawings at Windsor Castle, briefly allowed the possibility that the bearded man might be a portrait of the artist.

Clayton argues that “an image of Leonardo done from the life in a casual moment is maybe trivial as a work of art but hugely important, even moving, as a record of the man himself”. Despite achieving fame in his day, Leonardo remains a mysterious figure to scholars. His copious scientific writings offer few clues to his state of mind and the documentary record of his life is sparse compared with other Renaissance artists. “Trying to get some insight into his motivations is not easy,” Clayton says. “Any little bit of evidence is another piece of the jigsaw.”

• Leonardo da Vinci: a Life in Drawing, The Queen’s Gallery, London, 24 May-13 October