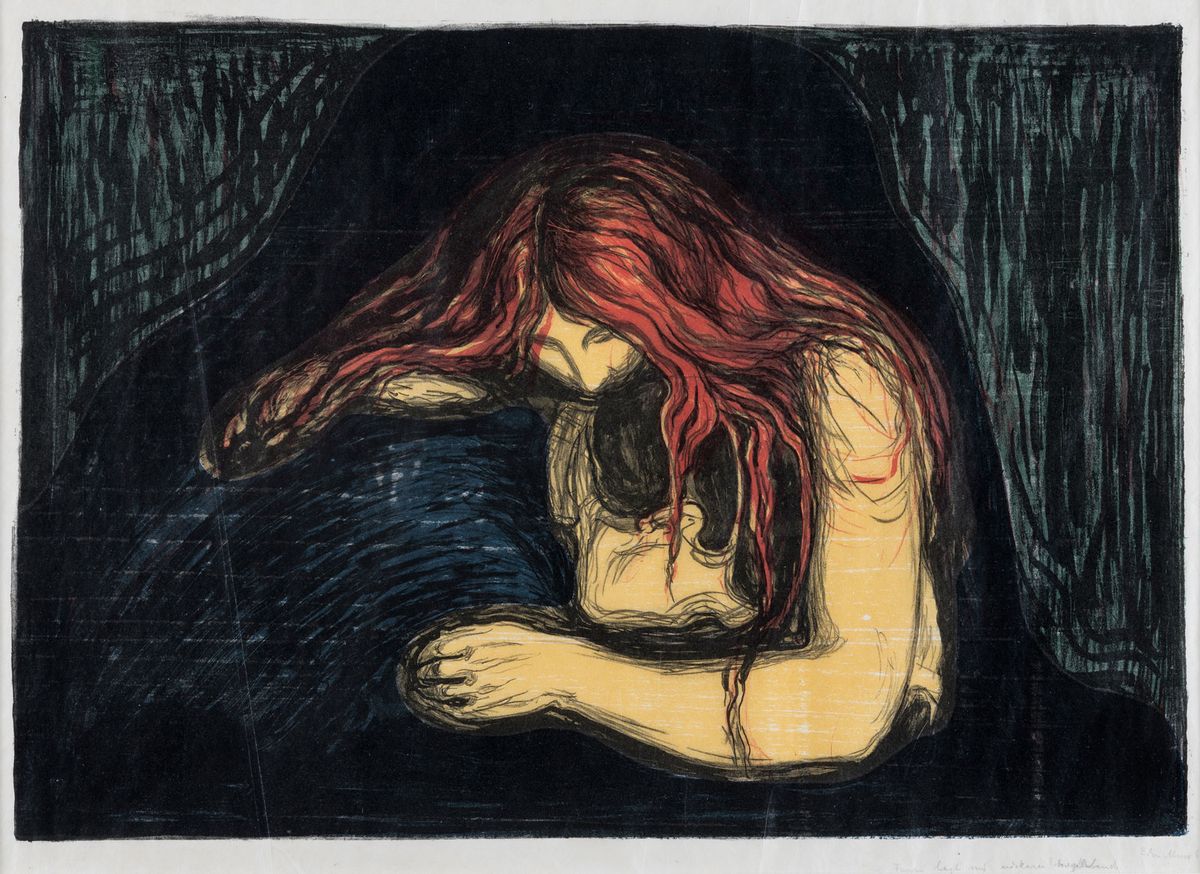

Edvard Munch aimed to make an art “that arrests and engages… an art of one’s innermost heart”. His graphic work, like the rest of his oeuvre, is arresting; the contents of his heart are deeply depressing. While it is undoubtedly a good thing that he was one of the first artists to have had the courage to record the darkness of the soul, a little goes a long way. A survey of the Norwegian artist’s printmaking, titled Edvard Munch: Love and Angst, opened this week at the British Museum (until 21 July; tickets £17, concessions available). The subtitle correctly describes the “angst” in Munch’s art—the Germanic word is packed with a range of emotions (anxiety, fear, anguish, agitation, insecurity)—but “love” is hard to find. The works display sex in plenty—but of tenderness, sympathy, rapport or simple romance there is none. His prints and drawings of sick and suffering children reveal, however, a caring heart. His career effectively came to an end as he entered the final decades of his life, and alcoholism and depression took their toll. In retrospect, it could be justly said that in his end was his beginning.

Van Gogh and Britain (until 11 August; tickets £22, concessions available) at Tate Britain shows how many things the Dutch artist liked about our country. He liked British print-making—collecting more than 2000 “black and whites” during his time in London—and he loved the novels of Charles Dickens. In return we have shown the painter a fair share of admiration—most notably through our national obsession with his Sunflowers (on loan here from the National Gallery), which revitalised the production of modern British flower paintings. It is difficult to find fresh narratives within what must be one of the most canonised stories in art history. Unsurprisingly then, one of the most interesting parts of this exhibition (for which The Art Newspaper’s long-standing correspondent Martin Bailey served as an expert advisor), lies beyond Van Gogh’s life. In the final rooms his legacy is continued with reverent and powerful works by Francis Bacon and David Bomberg, and the role that English publications and a 1910 exhibition Manet and the Post-Impressionists played in his immense popularity is well focused upon.

Monkeys have whimsically clambered up a scaffold-like structure at the Victoria Miro gallery on Wharf Road. They represent characters from old Marathi satirical theatre and, like most works in the NS Harsha exhibition (until 18 May; free), combine a playful presence with the weight of ancient tradition. The show’s central work Reclaiming the Inner Space (2017) covers the entirety of a wall upstairs at the gallery with around 1,400 wooden elephants roaming on a plain of flattened cardboard packaging attached to mirrors, upon which Harsha has painted constellations of stars and planets. The figurines resemble both the kitschy carvings made by local artisans found on Indian roadsides and the celebratory elephant processions in the Indian artist’s hometown of Mysore. Harsha’s work alludes to the conflicting dynamics that arise in the efforts to modernise a vast subcontinent filled with very particular ancient traditions and varying social structures. In the painting Smears to weave her everyday (2019), a mat used by street vendors is painted like the fabric of the universe. As elections get under way in the world’s largest democracy, Harsha’s merging of the quotidian and the cosmic takes on a poignant relevance.