The London dealer Richard Nagy is making a bold statement at Art Basel Hong Kong with a booth of around 40 works solely devoted to Egon Schiele (1890-1918). The whole show, which includes many works that are not for sale, is insured for an eye-popping $100m.

Schiele’s work is intense and challenging, with a raw sexuality. The artist was briefly imprisoned in his lifetime for exhibiting his erotic drawings. “Schiele explores the human condition at the most elemental level,” Nagy says. “There is generally no background… just a focus on the figure.”

This is a narrow market: firstly because of the prices, which start at $100,000+ and rise to $12m in Nagy’s show; this hardly gives an opening to young collectors. And secondly, because of the need for connoisseurship to appreciate many of his works—the delicacy and tenderness of some drawings, but also the angst and the physical tension.

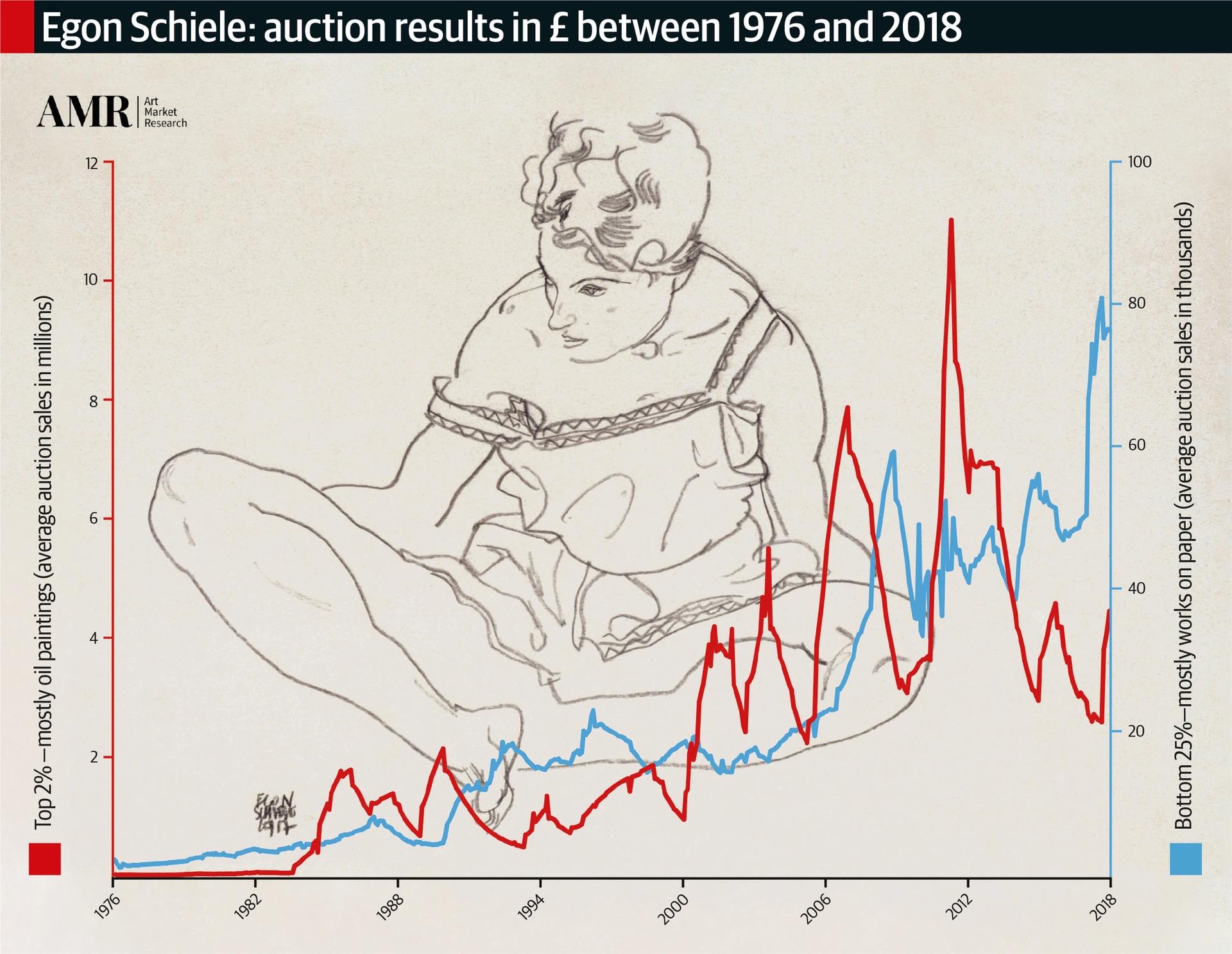

Schiele’s Adele (Seated Woman with Crossed Legs), 1917 Graph: courtesy of Art Market Research 2018. Adele: private collection, courtesy of Richard Nagy

Prices

The price index Art Market Research has tracked auction results for Schiele works, showing the explosion in prices since 2000. In the period between 2000 and 2017, they grew by 1,122.9%.

“In the 1940s a Schiele could be bought for just $20, and by the 1950s, for $100,” says the leading authority Jane Kallir, the author of the Schiele catalogue raisonné, and the director of New York’s Galerie Saint Etienne, which was established by her grandfather Otto in 1939.

The highest prices go to Schiele’s oils, which are much rarer than works on paper: the auction record is a stunning £24.7m ($39.82m), given at Sotheby’s London in June 2011 for Häuser mit bunter Wäsche (Vorstadt II) (Houses with laundry (Suburb II), 1914). It was estimated at £22m-£30m, so sold within its target (pre-sale estimates do not include fees; results do).

But in 2017 there were two failures of other large oils. Danaë (1909) was withdrawn from sale at Sotheby’s New York—its estimate of $30m-$40m was considered punchy for a work heavily influenced by Schiele’s teacher Gustav Klimt. Another high-profile oil that failed to sell was Einzelne Häuser (Häuser mit Bergen) (Single houses (Houses with mountains), 1915), probably because the £20m-£30m estimate was too high.

As for works on paper, the record is for Liebespaar (Selbstdarstellung mit Wally) (Lovers, Self-portrait with Wally, 1914 or 1915), which made £7.9m ($12.3m) at Sotheby’s London in 2013.

Nagy and Kallir agree that the main problem in this market is supply, which is thinner than in the past. “There is no way anyone today could put together a group such as that owned by the Leopold Museum in Vienna,” Kallir says.

On 26 February, staff at Sotheby's London took telephone bids for Egon Schiele’s Triestiner Fischerboot (Trieste Fishing Boat), which sold for a hammer price of £9,200,000 Photo: Stephen Chung/Alamy Live News

Pitfalls

There are two issues of which collectors must be aware. One is provenance: some of Schiele’s work was looted in the Second World War by the Nazis. It is important to do due diligence in all cases, consult the catalogue raisonné and look carefully at who owned the piece in the 1930s and 1940s.

In some cases, when a work is found to have been looted, an arrangement with the current owners can be made. For example, in New York in November 2018, Sotheby’s offered a work that had been stolen and, ultimately, restituted to the family of the original owners: Dämmernde Stadt (Die kleine Stadt II) (City in Twilight (The Small City II), 1913). It made $24.6m.

Most fakes get weeded out before they can travel very far up the food chainJane Kallir, author of the Schiele catalogue, raisonné

The other pitfall could be authenticity. There are cases of fakes on the market and Kallir says she sees about one a week. “Fortunately, most fakes get weeded out before they can travel very far up the food chain, and the catalogue raisonné serves as a reliable safeguard,” she says.

There are also works that were coloured after Schiele’s death by his brother-in-law Anton Peschka; these generally have far less value than a work entirely by Schiele.

The content of some of Schiele’s work, with brutal frontal nudity, might seem challenging to public Asian values. But Nagy says: “The Japanese have a vibrant tradition of shunga [erotic images] while at the same time behaving with decorum in public, so I don’t see why other individual buyers should be different… erotica has a universal appeal.”

According to Nagy, the more naturalistic and instantly recognisable works dating from 1917 and 1918 have recently attracted high prices and some “trophy hunters”, although true Schiele aficionados favour the more challenging Expressionist works from 1910-12.

Egon Schiele, 1914. Photograph By Anton Josef Trcka

Collectors

According to Jane Kallir: “There are trophy collectors who only want A++ works, and this pushes some prices into the stratosphere; as a result, the market is becoming bifurcated. At the lower end of the Schiele market, there are some great bargains to be had by connoisseurs, who have a deeper understanding of the artist.”

As for Asian buying, Richard Nagy says he already has some Chinese collectors, “but barely a handful”. However, at Sotheby’s London on 26 February, Triestiner Fischerboot (Trieste fishing boat, 1912) made an over-estimate £10.7m ($14m) and was underbid by Asians, according to the auction house.

Nagy is showing Schiele in Hong Kong because he is hoping to find new collectors for the work, and “because we want to fly the flag for the artist”, he says.