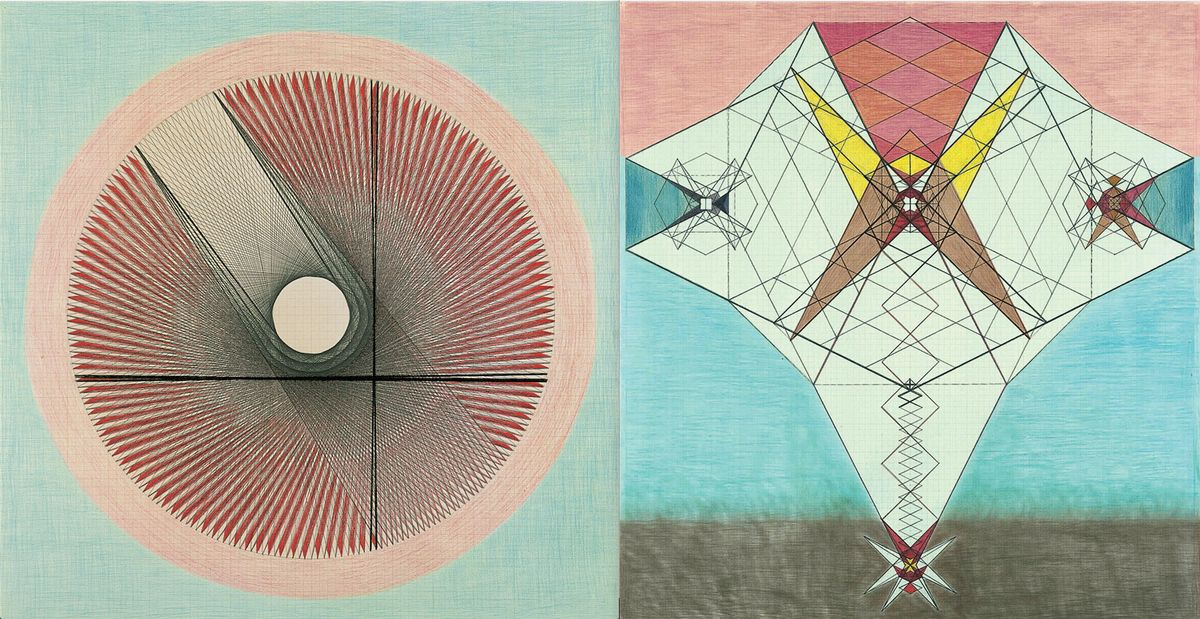

The Serpentine Gallery has been transformed into a site for quiet meditation through the works of the Swiss spiritualist Emma Kunz (1892-1963). Visionary Drawings (23 March-10 May; free), which opens tomorrow, includes around 60 drawings that Kunz made throughout her life as aides to healing sessions that she performed. But it is the formal qualities of these abstract drawings, rather than any spiritual elements, that are mesmerising. Kunz used a pendulum to dictate the marks of these surprisingly large drawings (most are just under one metre squared) made on graph paper using very measured and deliberate mark-making using pencil and coloured crayons. She created more than 500 in her lifetime but never exhibited them, predicting instead that they were most suited to the 21st century. The exhibition, the first significant show of her work in the UK, has been curated in collaboration with the Cypriot artist Christodoulos Panayiotou who has created stone benches made from Aion A, a rock named by Kunz that is said to have healing properties, to accompany the works.

A display of defunct, rusting industrial machines, which went on show earlier this week at Tate Britain in the Duveen Galleries (until 6 October; free), point to the decline of British industry and its welfare state post-war, says the artist Mike Nelson. His installation, The Asset Strippers, includes post-industrial remnants sourced online via auctions organised by company liquidators and salvage yards. The objects on show include knitting machines from textile factories, metalwork lathes and haulage parts. Nelson has also created partitions from wood stripped out of a former army barracks in Shrewsbury while some of the side doors are from a hospital in Bolsover Street in London, bringing to mind the welfare state that has deteriorated since the 1980s, he says. The project was also informed by Nelson’s wish to return the Duveen Galleries, the first purpose-built sculpture galleries in England which opened in 1937, to “halls for monumental sculpture”. (For more about the display, see ‘State decline, spawning vanity and inequality’: Mike Nelson's Tate Britain show offers bleak portrait of UK).

The Spanish painter, Joaquín Sorolla y Bastida (1863-1923) was an international star in the years before the First World War, comparable in style and fame to John Singer Sargent and James Abbott McNeill Whistler. Now, a century after his last major show in the UK, the Spanish artist’s works have gone on show at the National Gallery in the exhibition Sorolla: Spanish Master of Light (until 7 July; tickets £18, concessions available). Sorolla’s work, so accurately encapsulated by the subtitle of this show, “master of light” consists of outsized sun-dappled nudes, sea- and landscapes, drawing room scenes of the wealthy, as well as swagger portraits with swirls of fine textiles. These pictures were avidly acquired by the newly rich haute bourgeoisie in Spain, France and notably in the US. Although he remained a perennial favourite in Spain (there is a Sorolla house museum in Madrid), his work, wholly void of unease or menace or intellectual exigency, completely dropped out of the picture after the war. British viewers will no doubt find new pleasures in the works of this highly talented decorative artist.