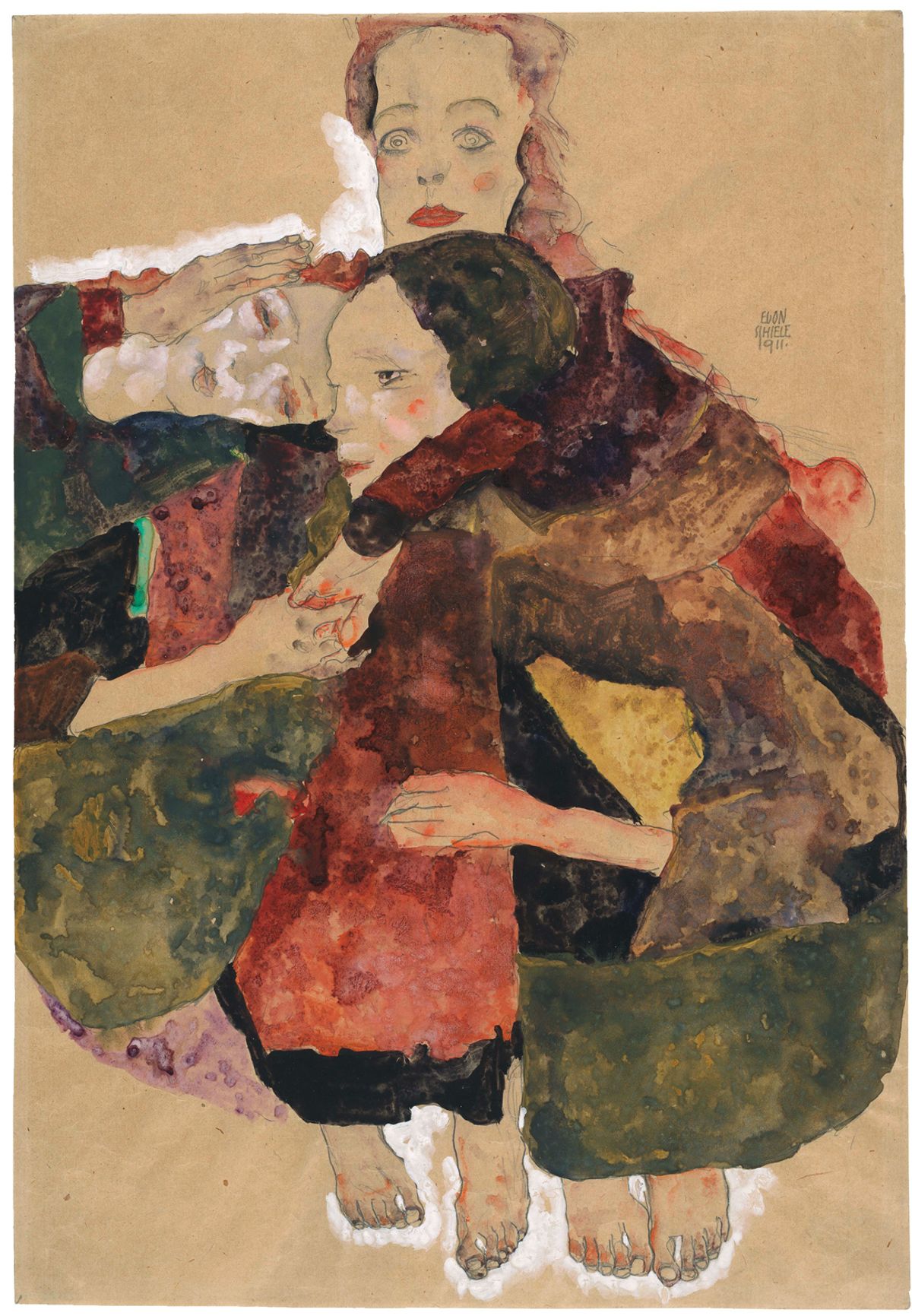

To mark the anniversary of the deaths of Gustav Klimt and Egon Schiele in 1918, Vienna’s Albertina Museum has loaned 100 of the artists’ works on paper to the Royal Academy of Arts for the exhibition Klimt/Schiele: Drawings from the Albertina Museum (4 November–3 February 2019), opening on Sunday. Both artists’ drawings and paintings on paper, especially Schiele’s, still have the power to shock—raw, bordering on fetishistic in their focus on genitalia, both male and female—yet one is left wondering, what happened to it all? Why did the influence of Klimt and Schiele, the Vienna Secession and the Werkstätte fail to develop further. Part of the answer lies in the fact that the cosmopolitan Austro-Hungarian Empire (in which 11 languages were officially recognised) fragmented into ethnic nation-states in the same year these two artists died. A reduced Austria did not have the cultural or material resources to support such an artistic milieu. Be that as it may, there can be no doubt that the period of the Secession and its subsequent variations were unique, as this exhibition shows so clearly through works on paper. When Klimt and others broke from the Academy to form the Secession in 1897, they gave it the motto, “To the age its art, to art its freedom”. That freedom was essential to Schiele and Klimt who forged a new age of art. The fact that these two innovative artists had no successors does not diminish their greatness.

It is the last chance to see the immersive exhibition Gush (until 4 November) at Somerset House by the young UK artist Hannah Perry. Car engines rev, orchestral strings hum and a voice asks: “Could I have said one small thing to make you happy?” Perry’s 360-degree film installation, titled Gush (2018), explores mental health and experiences of memory, trauma and loss. The themes strike a personal note for the artist whose best friend and artistic collaborator Pete Morrow took his own life in 2016. Morrow is remembered in the striking film through his writing, which partly inspired the script for the soundtrack made in collaboration with the musicians Mica Levi and Coby Sey. The show also looks at how trauma and shock can gradually damage us, and is evoked in a series of hydraulic sculptures that dance around each other, occasionally crashing together, slowly destroying their pristine finish. Perry spoke to The Art Newspaper last month about the show.

It is also the final chance to see Mika Rottenberg’s first major London show (until 4 November) in the capital’s newest public gallery, Goldsmiths Centre for Contemporary Art. The exhibition spans the Argentine artist’s career to date, from her degree show work, Mary’s Cherries (2004), to recent pieces such as Cosmic Generator (2017-18). The exhibition gives us an insight into the development of Rottenberg’s visceral video works and installations that often immerse viewers in a world bordering on the surreal but anchored enough in reality to offer real bite. In the video installation NonNoseKnows (Artist Variant) (2015), the hand operated fan inducing the protagonist’s noodle-making sneezes, is driven by a worker in a Chinese pearl cultivating factory. The surreal food production method juxtaposed with the dextrous but monotonous labour of the factory workers is mesmerising but also deeply disturbing.