The 100th anniversary of Egon Schiele’s death has arrived just in time for the #MeToo movement. Commemorative exhibitions are taking place this year in Moscow, Boston, Vienna, Paris, London, Liverpool and New York City, too, when the Met Breuer presents a show (3 July-7 October) on Scofield Thayer, the first US Schiele collector. Responding to the ongoing focus on sexual harassment, Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts saw fit to add wall labels addressing the artist’s alleged mistreatment of women for its Klimt and Schiele exhibition (until 28 May). When the contemporary artist Chuck Close was accused of sexual harassment, the New York Times gratuitously included Schiele in its pantheon of historical artist-abusers. In the furore of our current moment, it is easy to forget that every allegation of abuse must be weighed according to its specific merits. Schiele’s relationships with women are difficult for us to judge, not only because no living witnesses survive, but also because present-day standards are so very different from those that prevailed in early 20th-century Austria.

The specific allegations centre on three aspects of his life and work: his arrest for “public immorality” in 1912, his treatment of the various women in his life and the erotic nature of his drawings. In each case, however, the allegations are not justified by the facts.

The so-called prison incident took place when Schiele was living with his model and lover, Wally Neuzil, in the rural town of Neulengbach. The “incident” was precipitated by a teenage runaway, who asked the couple to take her to her grandmother in Vienna. Once in the city, the girl got cold feet, and the three returned to Neulengbach a day later. By then, however, the teenager’s father had filed charges of kidnapping and statutory rape, which led the police to conduct a thorough investigation of the artist. In the course of that investigation, a third charge was levelled against Schiele: that he had committed the crime of “public immorality” because the minors who hung out at his studio after school had allegedly been exposed to erotic works of art. Although the court records do not survive, it may be assumed that the first two charges were dropped because they were not warranted by the actual circumstances. The third charge, however, stuck, and the artist was sentenced to 24 days in jail, 21 of which had already been served awaiting trial.

By all appearances, Schiele’s sexual escapades were fully in keeping with the norm for a bourgeois young man. Because males were not considered suitable marriage partners until they had established themselves professionally, they were expected to spend their early 20s consorting with prostitutes and lower-class lovers. Most of these prostitutes were minors; the age of consent in fin-de-siècle Austria was 14. And since any woman who earned her living in the buff was considered to be morally compromised, the line between prostitution and modelling was slender. It is less surprising that Schiele had brief liaisons with his models than that his affair with Neuzil developed into a meaningful professional and personal partnership lasting four years. Nor is it surprising that, shortly before his 25th birthday, Schiele rejected Neuzil in favour of a more suitably bourgeois marriage partner, Edith Harms.

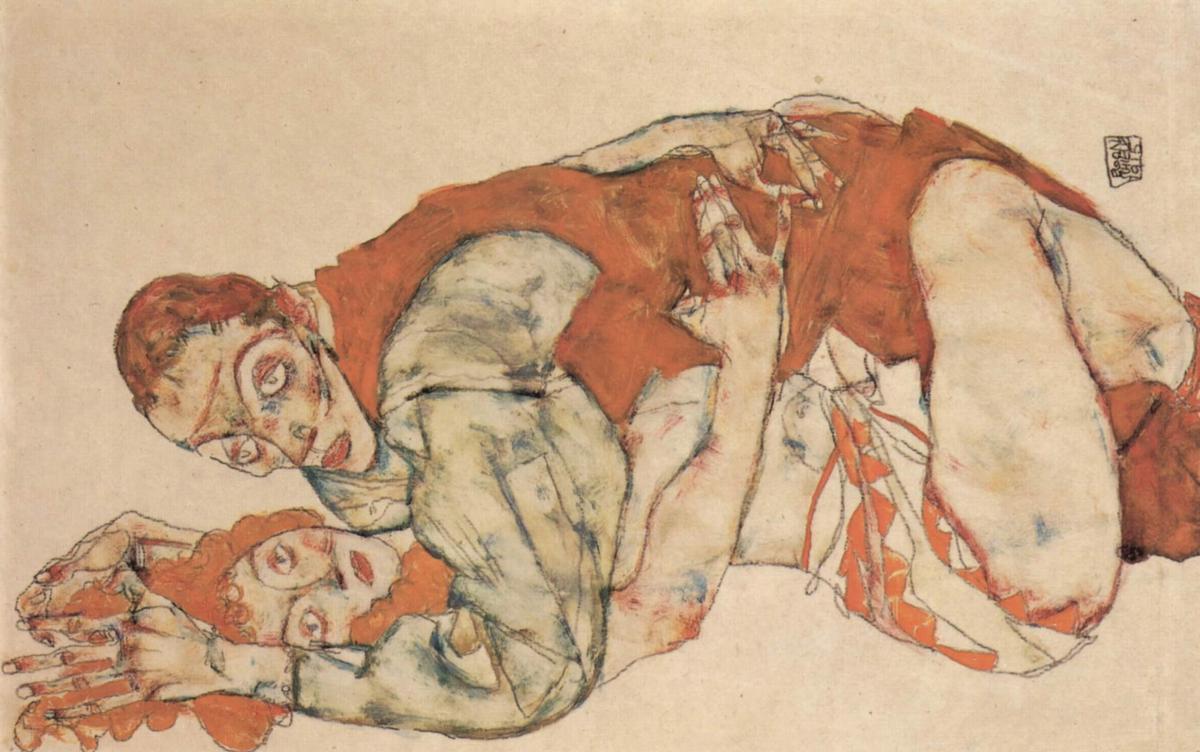

Schiele’s erotic drawings are disturbing to some because of the many ways in which the artist subverted established convention. Instead of being passive receptacles for masculine desire, his nudes are bluntly confrontational. Frequently, Schiele asked his model to lie on a mattress placed on the floor, while he perched above her on a stool or ladder. By omitting any surrounding detail from his drawings and frequently giving recumbent figures a vertical reading, he created a profound sense of spatial dislocation. The resulting tension between the subject and the edge of the picture plane calls into question the ability of the latter to contain the former. Even by today’s standards, these drawings grant women an uncommon degree of sexual agency.

Schiele was, of course, hardly a feminist. Current views on gender have been decades in the making, and he was very much a product of his time and place. However, unlike many men then and since, Schiele embraced the mix of fear and attraction that often colours masculine responses to the female “other”. As a result, he created images of women who, mirroring his own ambivalence, boldly command their sexuality. Is that sexuality truly a kind of superpower, or does feminine allure inevitably entail capitulation to the patriarchy? The enduring relevance of great art lies in such questions, in ambiguous readings rather than simplistic formulations. To brand Schiele a sex offender is not only wrong; it ignores essential historical context and forecloses necessary dialogue.

• Jane Kallir is the author of the Egon Schiele catalogue raisonné and the co-director of Galerie St Etienne in New York