Things Fall Apart, Calvert 22 (until 3 April)

This important exhibition examines the little known (by me, at least) history of the way in which, during the Cold War, the Communist Bloc supported and invested in cultural and political development in Africa and beyond. Through the work of 11 international contemporary artists, we are given a fascinating insight into some of the ways in which the Soviet Union supported independence struggles in Africa and in the developing world and how it attempted to wield soft power through film and art.

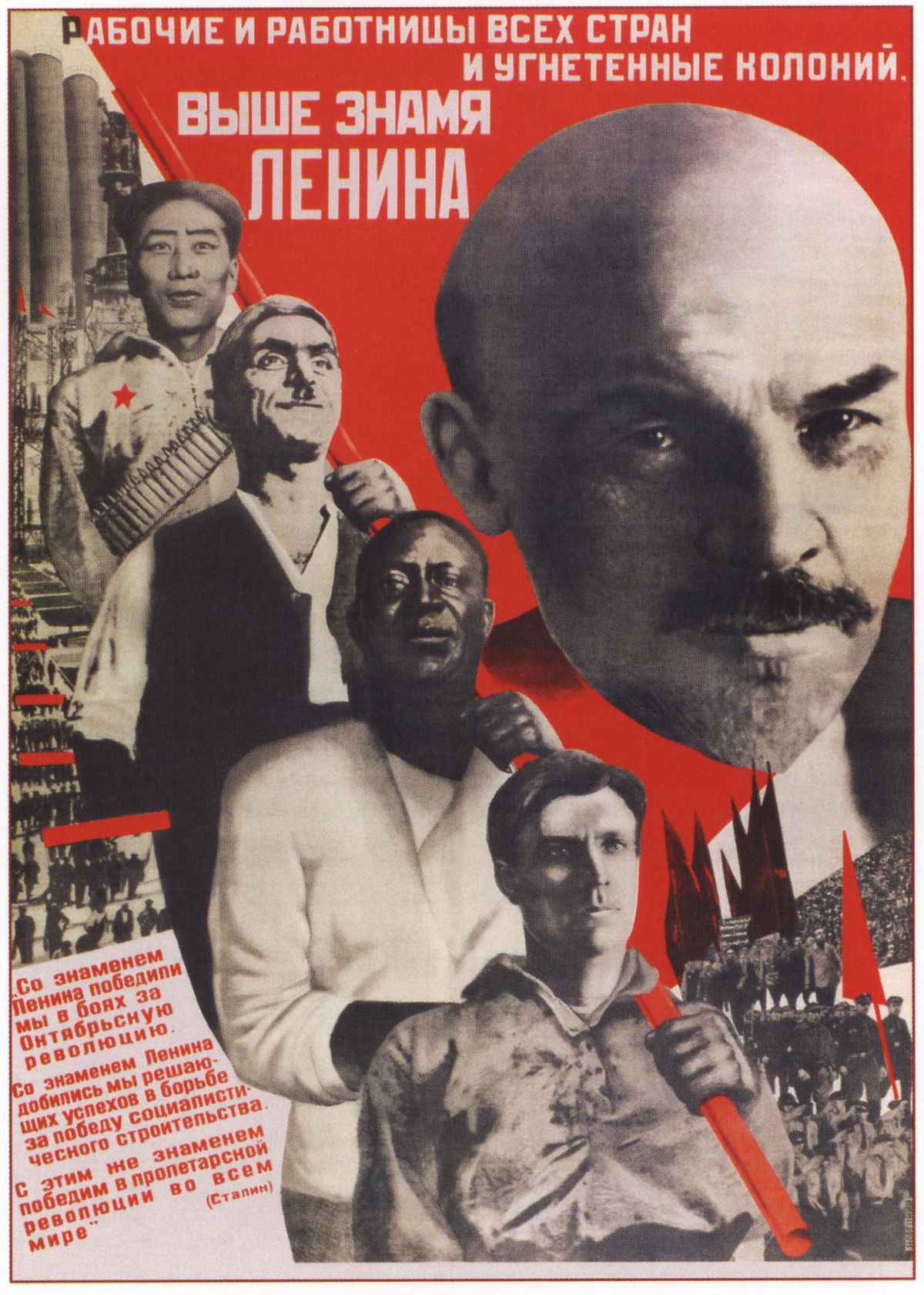

Around 200 Soviet propaganda images from the 1930s onwards collected by the New York-based artist Yevgeniy Fiks provide immediate visual expression of the links between Africans and the Soviet Union as, shown here in projected digital form, African people are depicted alongside and often arm-in-arm with Russians. The archive is named after Wayland Rudd, an African-American actor who emigrated to Moscow in 1932; and it reveals that a second more significant wave of Africans came to study, and sometimes settle in, the USSR in the later 50s and early 60s, as the country provided military and diplomatic support to countries such as Angola, Mozambique, Egypt and Congo.

St Petersburg-based Alexander Markov documents how Soviet propaganda films recorded the expansion of “glorious socialism” across the African continent, while photographs by Britain’s Isaac Julien explore how, under its revolutionary government, Burkina Faso became the centre for cinema in Africa. Others examine the wider cultural dissemination of communism, such as Tonel from Cuba, who spoofs the historical relationship between his homeland and the USSR with an idiosyncratic spin on the space race. Then there is the revelation by South Korean Onejoon Che, who has spent the last few years charting the plethora of Socialist Realist statues of independence-era leaders and anti-colonial monuments donated from the 1960s onwards by North Korea to the public spaces of Senegal, Ethiopia, Kenya and Namibia—to name but a few—as part of the Korean peninsula’s Cold War. And apparently the North Koreans are still supplying monuments to some African states—although no longer free of charge.

Subodh Gupta: Invisible Reality, Hauser & Wirth Somerset (until 2 May)

Subodh Gupta’s trademark cooking pots are in abundance in his current show at Hauser & Wirth’s Somerset outpost. Gleaming steel vessels sprout like bizarre clusters of shiny fruit from a life-sized stainless steel tree that greets visitors in the farmyard, while inside a huge burnished brass pot dangles from the rafters of the ancient threshing barn. Rather less pristine are the grimy salvaged aluminium utensils squashed into panels like mini-domestic John Chamberlains, or the battered multitude of pots and pans that are suspended in their hundreds to form the shape of a giant pot.

Overall there’s not much of the homely about these vessels. The shiny, clinical artificiality of the tree jars with the bucolic Somerset surroundings, while the first view of the gong-like, beaten brass bottom of the threshing barn pot belies the fact that on the other side it is brimful of barbed wire. There’s a suffocating violence to the room full of flattened utensils, heightened by the slivers of vivid Indian fabric trapped at their edges, and an elegiac feel to the swarm of empty dangling kitchenware that carries so many traces of past sustenance. However, this lack of homeliness—or unheimlich, as Freud put it—is given full throttle in a dramatic new work in which a traditional wooden house from Kerala, in southern India, periodically exudes beams of dazzling white light, while reverberating metal panels on the gallery walls give off thunderous blasts. This sensory assault literally bangs home Gupta’s underlying message that in today’s damaged, overpopulated, climactically changing world there are ever fewer places for comfort and refuge.

Tell it Slant: Frith Street Gallery, Soho Square (until 29 April)

Yet again proof positive that artists make some of the best curators, with Jeff McMillan’s small but perfectly sel ected exhibition of works by an eclectic span of artists that riffs on the richness and scope of the abstract drawing. Or, indeed, of drawing in general—with many materials and means of production here extending way beyond a line on paper.

The starting point is Emily Dickinson’s poem Tell All the Truth but Tell it Slant, and there are slants, coils, weaves and ripples aplenty in this plethora of stimulating proposals and unexpected conversations. There is conflict and co-existence in Polly Apfelbaum’s procession of vividly coloured, regularly repeated, marker waves overlaid by slicing graphite lines, which owe their origins to national flags; or the clotted coils of the Belgian artist Joseph Lambert’s illegible but deeply expressive automatic writings that run in horizontal strata and look almost as if they have been knitted. A late Fabric Drawing by Louise Bourgeois finds a quiet symphony of tone and texture in a square of textile, while Pip Culbert runs a squiggly edge of a canvas awning along the wall and Tess Jaray plays with and off the inky slippages of her digital printer. Many truths indeed, from many angles….

Albert Oehlen, Gagosian Gallery, Grosvenor Hill (until 24 March)

Albert Oehlen continues to push at the perimeters of painting with this new series of utterly strange works, painted in oil on Dibond, a plastic-aluminum material usually used for trade fair stands, and in a restricted—but not by no means restrained—palette of black, white, petrol blue and magenta. Against the background of either the plain white plastic surface or sharp-edged but smeary blocks and patches of the blue and magenta, Oehlen paints the black outlines of trees—but not as we know them.

Although roughly tree-like, with branching appendages emanating from more solid centres, these silhouetted shapes assume a slightly hysterical life of their own: waving, stretching, connecting, dancing. Sometimes they resemble bizarre insects or schematic humanoids, bouncing off or held in check by chunks of screaming colour. These lines and blocks of black can be juicily applied, flat and sharp edged or fuzzily sprayed. According to Oehlen, trees “do all kinds of crazy shit with their branches… from that I concluded that my task as an artist was to make all kinds of crazy shit with my lines… you become a tree yourself and let your branches grow”. Certainly in these bizarre arboreal confections that are as much about abstract culture as organic nature, Oelhlen seems to be growing in all directions.